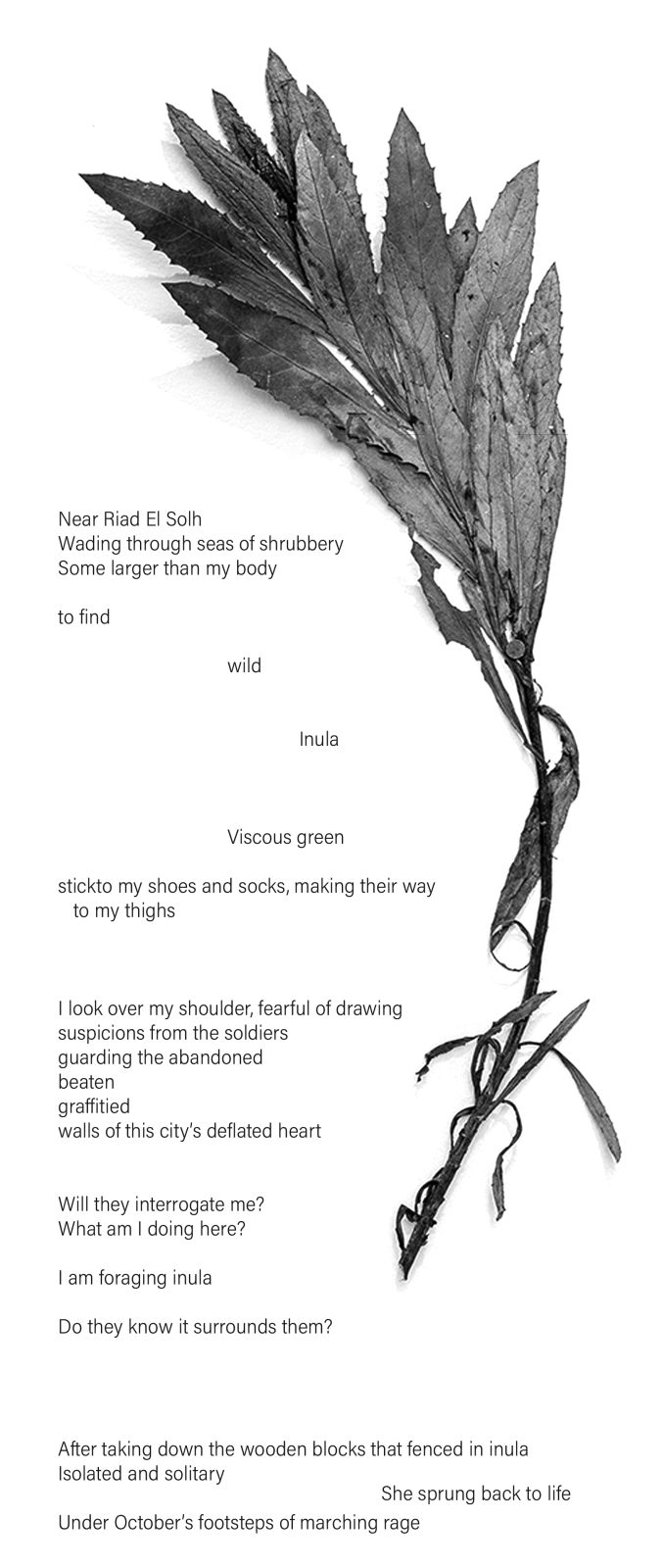

The protest on October 9, 2019, in Lebanon was initially in response to proposed taxes on WhatsApp calls but quickly escalated into a nationwide movement against government corruption, economic mismanagement, and inadequate public services. Unfolding in the heart of downtown Beirut, a district reshaped after the civil war with influences from French urban design, the protest gradually drew locals back to an area that had pushed them away. This event marked a pivotal moment, transforming the urban landscape into a vibrant hub for demonstrations. As the protests spanned several weeks, I found myself increasingly drawn to downtown Beirut. The removal of wooden barriers by protesters revealed previously inaccessible areas, inspiring me to explore the city’s hidden corners and focus on the unique vegetation thriving in these rediscovered spaces.

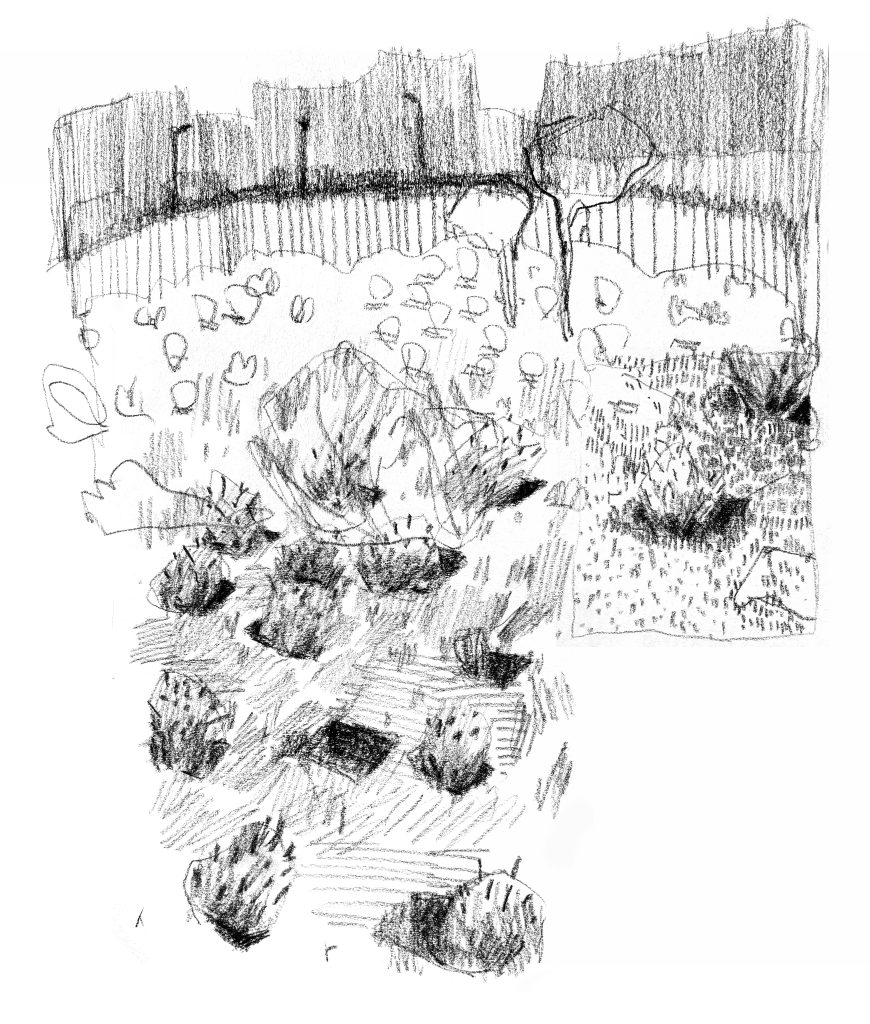

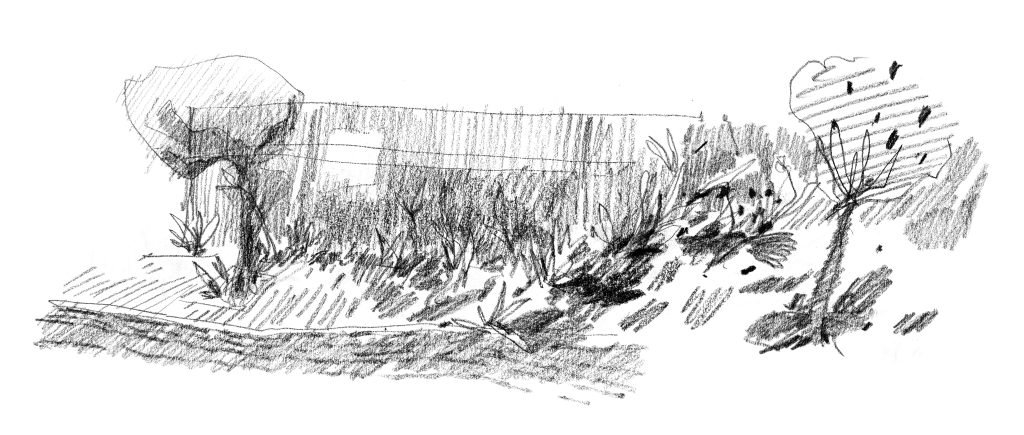

I started to have daily walks. Finding in walking a form to reclaim the city, to reshape my relationship to it, and to inhabit it with my body and all that inhabits it. One plot, adjacent to Riad el Solh square, captivated my attention and became my chosen destination. Initially slated for a multipurpose tower designed by Jean Nouvel, the project was halted when an archaeological site emerged during excavation. The plot’s allure lay in its six-meter-deep sunken walls, revealing faint traces of a stone structure that proved elusive to decipher. Notably, scattered across a significant portion of the plot were recurring holes, uniform in size—a rectangle now serving as a makeshift pot for one or two shrubs.

During one of my walks on the site, I crossed paths with Togo, a protester hailing from Bekaa, who had pitched a tent next to the plot. Togo relied on this area throughout the protest, foraging for his daily ingredients. He graciously took me on a brief tour, offering his unique perspective on the location of the frog pond and pointing out areas abundant with chard, mallow, nettles, and more. Conversations with Togo left me in awe. While foraging had been a fundamental part of my upbringing, finding a way to migrate that knowledge to the city had been elusive—until now.

Among local practitioners, there exists a shared ethos when it comes to foraging: take only what you need, leaving the rest for others, and allow the plants to rejuvenate for the next year. This mutual understanding forms a cognitive community centered around the plants, emphasizing the necessity of utilizing them for survival while also preserving them for the future. It harmonizes with the transient nature of the environment. Foragers grasp that the availability of foraged ingredients is confined to a brief period each year. To incorporate these elements into their diet year-round, foragers recognize the importance of preservation. Consequently, various preservation methods come into play, extending the availability of these ingredients while introducing alterations to their original state—be it through drying, fermenting, pickling, making compost, or crafting jams.

In essence, attuning oneself to the seasonality of nature imparts unique flavors and dishes to every season. Reflecting on my childhood, each year unfolded through the lens of the food we enjoyed. For me, the annual cycle commenced with the start of school, coinciding with the busy period of picking olives and producing olive oil and soap within my family.

Following this, the snail season marked the onset of winter, initiated by the first rain after summer. The colder months were navigated with an abundance of stews and soups, complemented by various herbal teas meticulously picked and dried in anticipation of winter’s arrival. Transitioning into spring, chards emerged, dominating the landscape and finding their way into dishes like Kebbeh, Manoushe, and various cooked pots. Our meals became enriched with an array of shrubs, either cooked or simply dressed with olive oil and lemon.

As spring and summer unfolded, fruits became remarkably accessible, creating a vibrant palette of flavors. However, the scent of jams being prepared signaled the impending end of the fruit season. From that point on, apples took center stage as my primary fresh fruit until the next season arrived.

Togo rekindled my passion for foraging, inspiring me to re-engage with this practice. However, now I find myself in the city, far from the familiar habitat of my upbringing where foraging feels natural. While foraging in the village represents a connection to the wilderness and a harmonious relationship with nature and its offerings, the implications of foraging in the city take on a different nuance, and so did my walks.

Unlike many cities, Beirut lacks communal gardens, and its relatively small size and underdeveloped infrastructure have contributed to a scarcity of public spaces. Over time, these spaces have been systematically taken away, gradually stripped and privatized. This has made it increasingly challenging to foster communal interactions without incurring a fee. In the face of these constraints imposed on our daily lives, foraging emerges as a tool that allows us to weave together the disparate elements of the city. It’s a means of navigating through spaces consumed by entropy—be it an empty parking lot, a small patch of soil near a pedestrian lane, or an abandoned construction site.

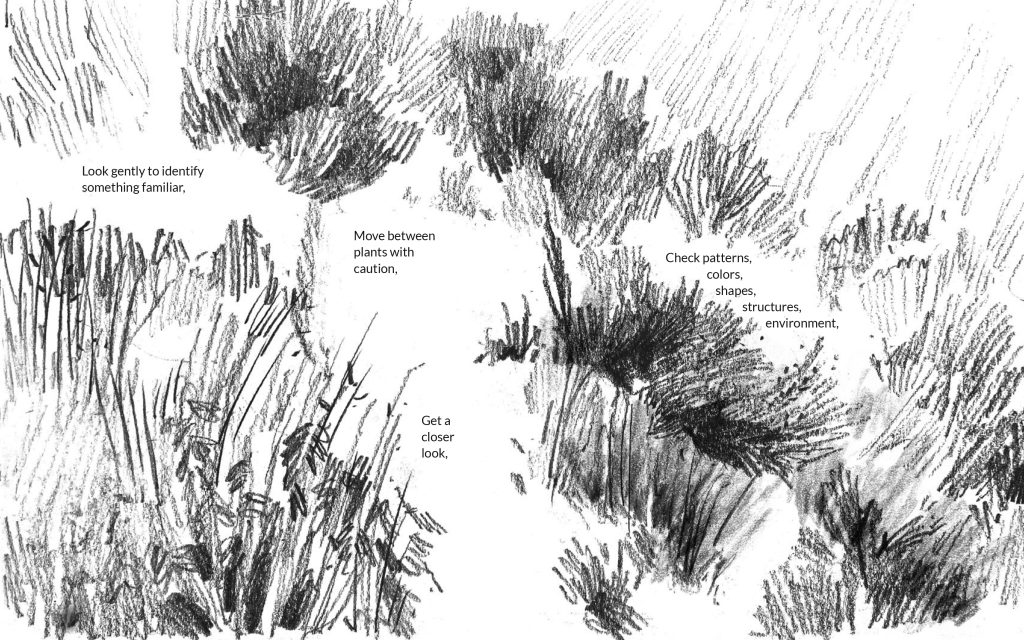

Through ancestral knowledge;

We walk on the lookout for edible shrubs;

We create alternative cartographies;

And through ancestral gestures;

We reconnect to the city.

Ursula Le Guin’s insightful exploration in “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” resonates profoundly as I navigate the urban environment. Le Guin challenges the traditional hunter-centric narrative, proposing that our ancestors were gatherers first, emphasizing the significance of containment over conquest. This shift in perspective aligns with my foraging endeavors in the city—a quest not for a singular conquest but a continuous act of gathering and containing, mirroring the essence of a carrier bag. In this bustling urban milieu where communal spaces are elusive and privatization prevails, the act of foraging becomes a symbolic carrier bag, a vessel for weaving together the fragments of the city, a means of embracing the role of gatherer, and challenging the cartographer

As I walk through the Riad el Solh plot again I come across Inula, also known as Tayyoun. It’s the pioneering plant that emerges in areas where the soil has endured substantial damage. Inula Viscosa, aptly nicknamed the Wound Herb (عشبة الجرح), showcases its robust nature by flourishing unapologetically through the cracks in roads and walls. Characterized by thick, sticky leaves with pointed edges, Inula acts as a natural plaster, aiding in the healing process. When its flowers bloom, they resemble butter daisies, with petals that are thinner and longer. As the flower completes its life cycle, the petals gradually give way, replaced by delicate white fuzz.

A fascinating aspect of Tayyoun is its method of seed dispersal. Mere footsteps near these plants create a gentle breeze, enough to rustle the tops of their stems, scattering seeds in the process. Perhaps it’s not entirely coincidental that this resilient plant, found abundantly across Beirut, possesses healing properties for indigestion and respiratory problems.

As I daily walked back from this plot in downtown Beirut to my studio in Sin el Fil, the landscape transformed as I became increasingly aware of the shrubs and trees accompanying me along the way. Among them, the Eucalyptus tree (شجرة الكينا) stood prominently, a lasting legacy of the French mandate era when reforestation efforts reshaped Lebanon. The French strategically planted these trees on roadsides and in swampy areas to combat moisture. Over time, however, the environmental impact of Eucalyptus trees became apparent, as their extensive root systems not only dried the soil but also depleted it of essential nutrients.

Despite these drawbacks, the short period of Eucalyptus settlement in Lebanon left an indelible mark on its citizens. I reminisce about my grandmother lifting a pot of boiling Eucalyptus leaves, urging me to inhale the vapor believed to alleviate coughs. Her house perpetually exuded the fragrance of Eucalyptus, leading me to diverge from my initial destination and follow the path of the Eucalyptus tree laid out before me.

Along the way as well, in Karantina, situated on the western bank of the Beirut River, the vegetation transitioned again. Karantina is historically known as one of the earliest quarantine stations of the Ottoman Empire, it is today home to a diverse community of migrants and refugees. Over the years, waves of displaced populations, from Armenians fleeing genocide in 1915 to Palestinian refugees after the Nakba of 1948, have settled in this area. Karantina also witnessed a tragic massacre in 1976, a dark chapter in Lebanon’s modern history, where Lebanese Muslims and Palestinians were victims of a far-right Christian militia. The area continued to host Iraqi Kurds fleeing Saddam Hussein’s rule and, more recently, received the first wave of Syrian refugees in 2013.

As people from different regions arrived, they brought seeds and planted them around their homes, introducing a variety of non-native species. This unintentionally created a new ecosystem that migrated with its human carriers. Notably, a towering Jackfruit tree, separating a five-floor building from the general security office, became a symbol of Karantina’s resilience. The tree bears fruits reaching the size of watermelons, with a rough and thick outer skin displaying a bumpy or spiky texture, changing color with ripeness from green to yellow or brown.

Back in my studio, I reflect on the immersive walks I take each time I visit downtown Beirut, sparked by the protest that initiated this entire journey. These walks allow me to trace my path from the village to the present moment, delving into the insights provided by various plant forms and the rituals I’ve come to embrace. In doing so, I contemplate the impermanence of our surroundings and the rich stories they hold.