Stretching from the Atlantic shores of Morocco and Mauritania up until the borders of Afghanistan, the Southwest Asia and North Africa region (SWANA) region has historically been marketed and perceived by colonial powers as a vast, barren, and lifeless desert expanse. This narrative relegated its rich tapestry of forests to a position of neglect and obscurity as they now face imminent threats to their existence.

Each of these forests has its own unique character. From the argan groves of Southwest Morocco and Algeria, where the resilient argan tree thrives, to the majestic cedars gracing the high Atlas Mountains, to the Levant’s enchanting mid-elevation forests home to a mix of evergreen pines and deciduous oaks, including the mighty Lebanese cedars and Cilician firs.

In the Sudanese region, high rainfall Savannah woodlands nurture a flourishing biodiversity with unique flora and fauna. Along the coastlines of Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula, marvelous mangrove forests not only host a wide range of biodiversity but also protect the land from flooding while serving as a barrier to encroaching deserts from the east. Lastly, the riparian forests, nestled along riverbanks, play a vital role in water regulation, quality improvement, and flood risk mitigation, serving as refuges for the unique species that define these forest ecosystems.

These ecosystems stand as a testament to nature’s remarkable adaptability. But the drivers of deforestation and environmental degradation have never been more menacing, and the looming specter of climate change adds an additional layer of urgency to their conservation.

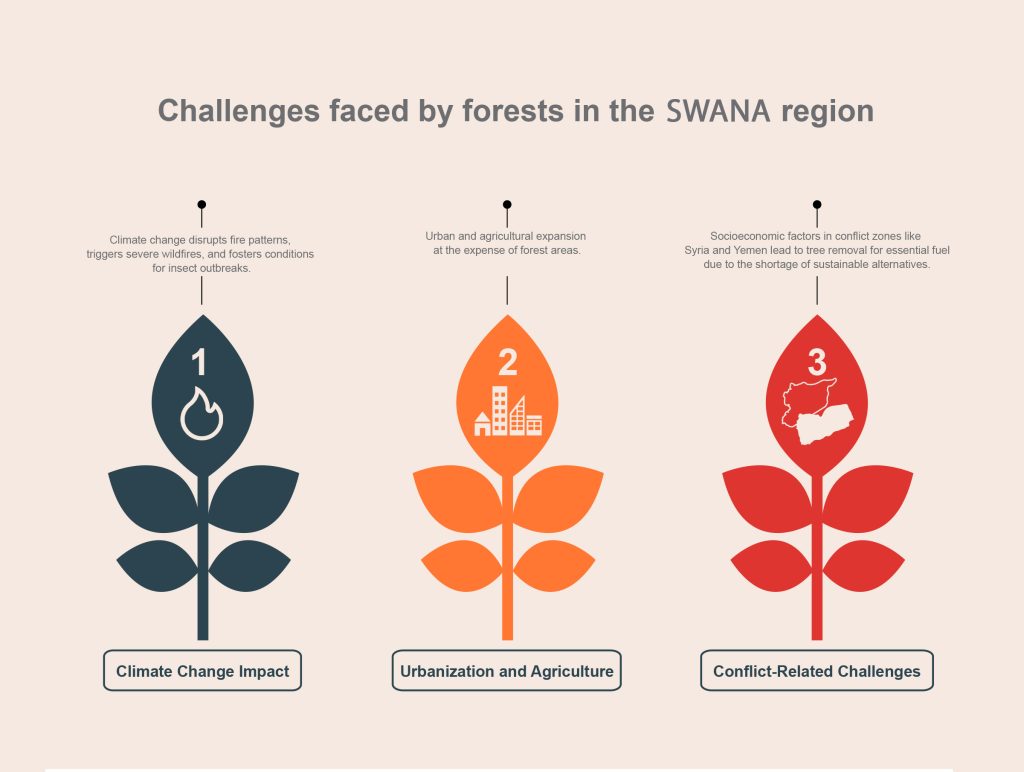

Despite their vital role in conserving biodiversity, sequestering carbon, and supporting local communities, forests in this vast region face serious threats to their area, health, and the ecosystem services they provide. These include climate change-induced challenges such as increased wildfire risks and prolonged droughts, as well as the encroachment of urban and agricultural expansion. Adding to that is the impact of conflicts or socioeconomic factors that compel the removal of trees for fuel due to the increase in poverty and the absence of sustainable alternatives.

Opening a gateway to a deeper understanding of these unique ecosystems and dispelling the age-old myth of this region as an arid wasteland, we invite you to embark on a journey of exploration of its various forests, providing insights into the challenges these forests confront and the critical need for their restoration. By doing so, we hope to kindle a sense of shared responsibility and inspire concerted efforts to protect them.

This article serves as an inaugural part of a dossier dedicated to the forests and green cover in the SWANA region and delving deeper into their complexities, intricacies, and remarkable stories. These forests are not just repositories of biodiversity; they are cultural treasures, economic lifelines, and ecological cornerstones.

A vital ecosystem

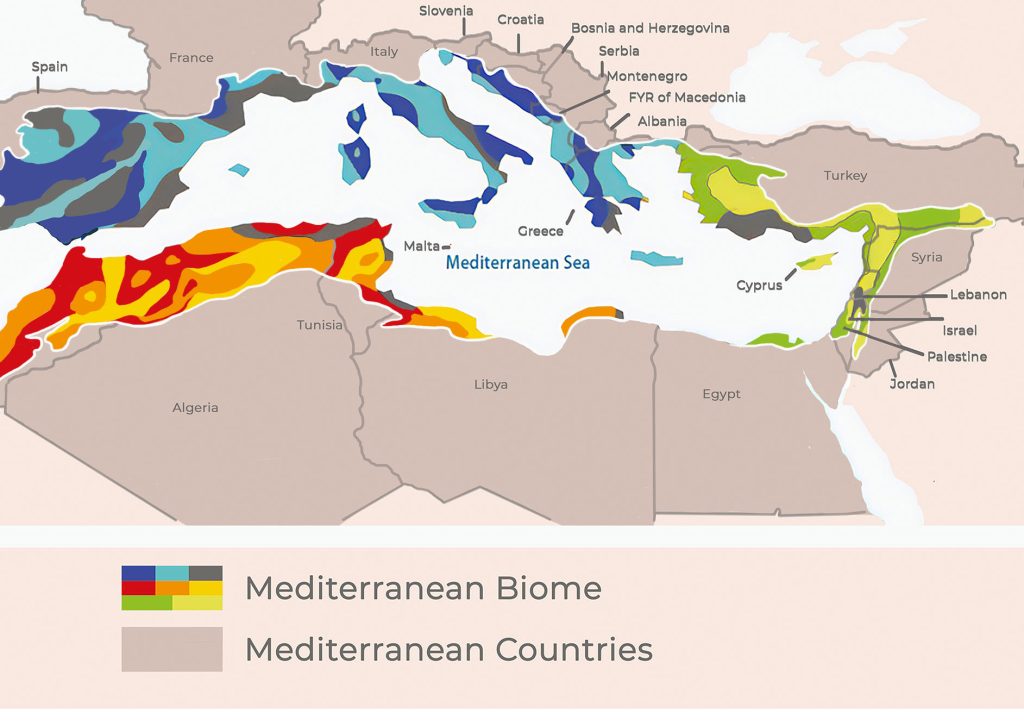

Forests in the SWANA region are of immense importance, not only for their exceptional biodiversity, but also for the substantial economic and social benefits they offer to local communities. They play a vital role in maintaining the delicate balance of ecosystems and are integral to the overall well-being of the region and the world. The region is home to forests that hold remarkable global significance due to their unparalleled biodiversity, despite facing severe threats. It includes forests that are prominently featured in four of the world’s biodiversity hotspots: the Mediterranean Basin, Caucasus, Irano-Turanian, and Horn of Africa regions. One notable highlight is the Mediterranean Forests, Woodlands, and Scrub ecoregion, renowned for hosting the world’s highest rate of plant endemism. With around 12,000 species, it accounts for nearly 50% of the regional flora, rivaling the renowned biodiversity of the tropical Andes.

Specific ecosystems within the region, such as cork oak forests, provide substantial social and economic benefits. For instance, in the Mediterranean forests of Northwestern Tunisia, the cork oak forests in the Iteimia area (Ain Snoussi region) contribute significantly to the local economy, supporting livelihoods and income generation. Similarly, in Morocco, the argan forests have gained international recognition for their unique ecological value, leading to improved economic opportunities and education for local communities. Conservation efforts have also been successful in preserving cedar forests, as seen in the Shouf Biosphere Reserve in Lebanon. This UNESCO Biosphere Reserve has become a hub for ecotourism activities, providing income opportunities for local communities and safeguarding a significant portion of Lebanon’s remaining cedar forests.

Non-Wood Forest Products (NWFPs) such as grazing, cork, fruits, and plants play a pivotal role in the region, contributing up to 40% of household income. Other ecosystem services like water filtering, watershed protection, soil fixation, carbon capture, and protection against erosion are also crucial for both the well-being of the natural ecosystems and the people living in them.

Nonetheless, these invaluable forests confront significant challenges, particularly from climate change, which is already exerting its influence on them in various detrimental ways. This includes the disruption of fire patterns, resulting in more frequent and severe wildfires, the onset of extended droughts, and the fostering of conditions conducive to forest insect outbreaks. Moreover, urban expansion and agricultural development present immediate threats to these forested regions. Last but not least, in conflict-ridden zones like Syria and Yemen, socioeconomic and sociopolitical factors often force individuals to resort to tree removal for essential fuel for cooking and heating, given the shortage of sustainable alternatives.

How history and colonial powers reshaped forests

Throughout history, the SWANA region has witnessed significant deforestation, with early examples dating back to Pre-Pottery Neolithic people clearing deciduous oak forests around 9000 years ago in Al Ghab valley in modern day Syria. The clearance of Lebanese cedar trees began around 7700 years ago. These actions led to the replacement of forests with secondary vegetation and cultivated plants, altering the lush green landscape as described in the epic of Gilgamesh. Now, few remains of cedar forests can still be seen in Mount Lebanon and Syrian coastal mountains.

In Algeria, during colonial time, the French army deliberately destroyed gardens, orchards, and landscapes surrounding major towns and cities as part of a scorched-earth policy to weaken the local population. Commercially, French companies heavily exploited Algerian forests, with the French army logging 300,000 cubic meters of wood between 1840 and 1848, and produced a significant amount of charcoal. Cedar and holm oak forests, particularly in the Aures and Jijel regions were targeted for logging. The scale of deforestation was substantial, with an estimated one million hectares of forests disappearing between 1870 and 1940. It has also been estimated that the wood production during World War II alone was about 1.5 million cubic meters, logging for firewood exceeded seven million cubic meters, and logging for charcoal production removed six million cubic meters of forests.

In an apparently opposite way, land transformation and reforestation were also strategically employed to rationalize and veil colonial practices in both the French and British mandates across the Levant and Maghreb regions. One illustrative instance of this can be found during the British Mandate in Palestine, where narratives of overgrazing and desertification were skillfully utilized to provide justification for forestry policies and the implementation of laws aimed at regulating nomadic communities, exemplified by the 1942 Bedouin control ordinance. These measures were ostensibly presented as essential for mitigating overgrazing. It is noteworthy that these colonial practices have persisted even in contemporary times, particularly in the Palestinian lands occupied by the state of Israel following the events of the Nakba. The Israeli authorities have undertaken extensive reforestation campaigns within the abandoned Palestinian villages, ultimately transforming them into nature reserves. This strategic effort can be viewed as an attempt to greenwash the forced displacement and ethnic cleansing experienced by the Palestinian population, thereby masking the true impact of these actions.

Forests declining at an alarming rate

Deforestation in northern Morocco and Algeria

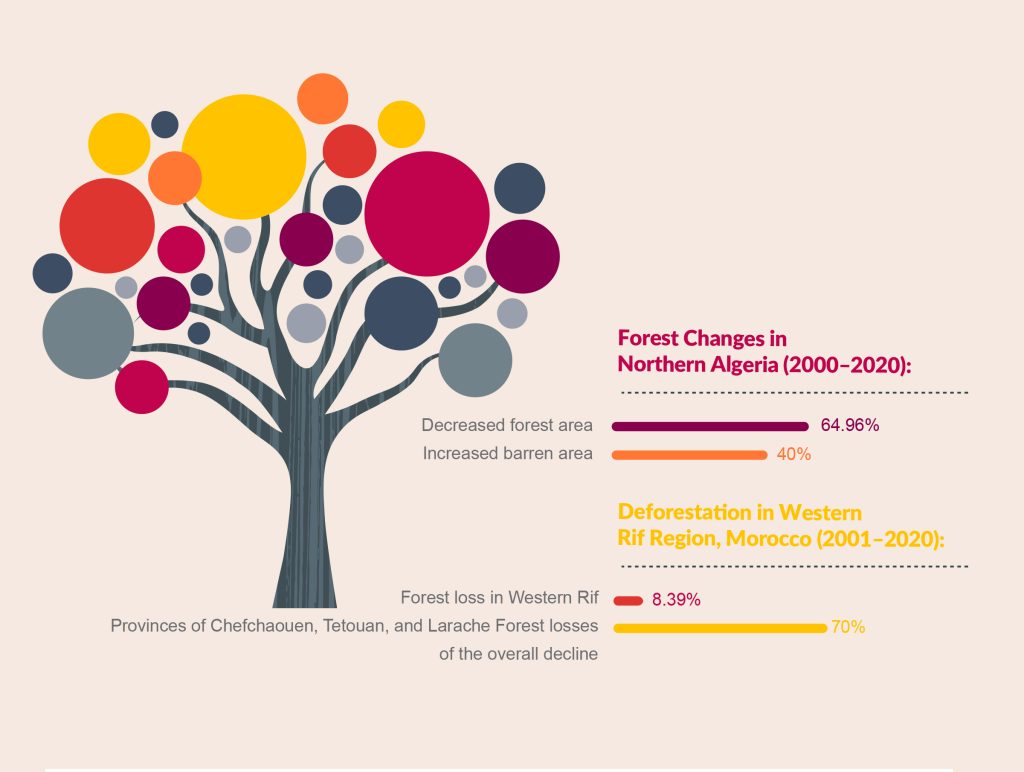

Forests in Northern Morocco and Algeria have witnessed significant changes in the last two decades. In northern Algeria, forest area decreased by 64.96%, from 3718 to 1266 km2, during the 2000–2020 period, while the barren area increased by 40%, from 134,777 to 188,748 km2. This decline can be attributed primarily to factors such as the expansion of agricultural land, forest fires, climate change and the complex interplay of sociodemographic, economic, and urban dynamics.

In Morocco and between 2001 and 2020, the Western Rif region has also been affected by deforestation, losing approximately 8.39% of its forested areas which is equivalent to a total land area of 272 square kilometers. Notably, the provinces of Chefchaouen, Tetouan, and Larache accounted for a significant portion of these forest losses, contributing to 70% of the overall decline. Moreover, the prefectures of M’diq-Fnideq and Tangier-Assilah experienced the highest annual deforestation rates, standing at 0.9% and 0.89%, respectively.

Mangrove deforestation in Egypt and Bahrain

Mangrove ecosystems along Egypt’s Red Sea coast, while relatively small, play a crucial role in the region’s environmental balance and biodiversity. These mangrove stands are scattered across sheltered bays and lagoons protected by coral reefs, covering over 550 hectares along the Gulf of Aqaba and the Egyptian Red Sea coastline. Unfortunately, over the past four decades, these vital mangroves have suffered a significant decline, primarily due to human activities and urban development along the coast. Factors such as climate change, environmental degradation, rapid urbanization, industrialization, tourism growth, and Bedouin grazing have all contributed to the depletion and degradation of these mangrove sites.

The situation varies along the different stretches of the Red Sea coast. In South Sinai, where mangroves serve as popular tourist destinations, the construction of new tourist facilities and oil pollution are causing extensive damage to the mangrove forests. This damage is resulting in the loss not only of these unique ecosystems, but also the diverse marine life they support.

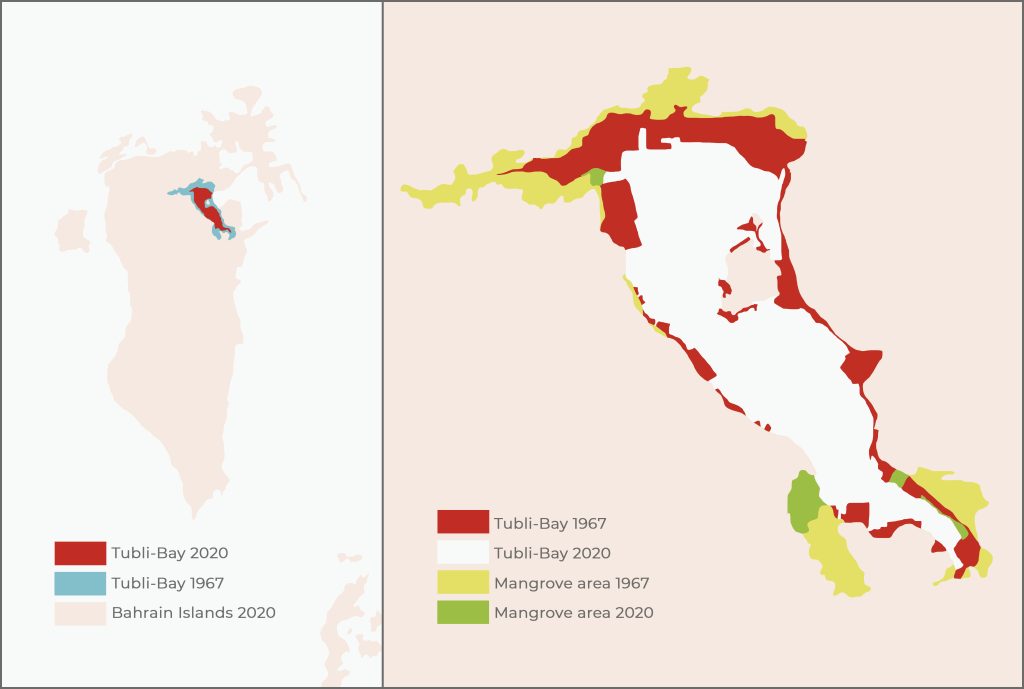

Over the span of more than five decades, Bahrain has experienced a staggering decline in its natural mangrove cover, amounting to a loss of over 95% from 1967 to 2020. This profound environmental transformation has resulted in a significant reduction in the extent of mangrove areas, with a net loss of 280 hectares recorded during the period spanning from 1967 to 2020. To put this into perspective, the mangrove coverage that once encompassed 328 hectares in 1967 has dwindled dramatically to a mere 48 hectares by the year 2020. This substantial decline highlights the pressing need for conservation efforts and sustainable practices to safeguard the remaining mangrove ecosystems in Bahrain.

War-induced deforestation: Syria and Yemen

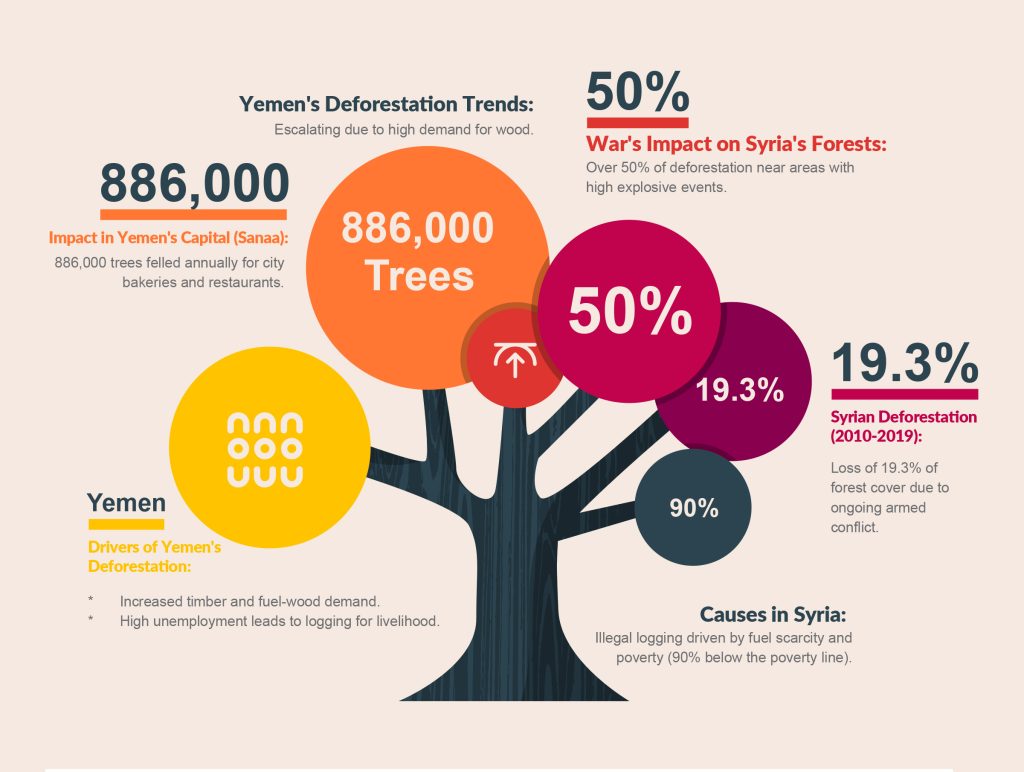

Syria lost about 19.3% of its forest cover from 2010 to 2019. This decline is primarily attributed to the ongoing armed conflict, which has unleashed a multitude of factors contributing to the decrease in forested areas. Among these factors, illegal logging activities carried out by both local inhabitants and refugees residing in camps with a proximity to forested regions have played a pivotal role. These logging activities were mainly driven by the lack of fuel for cooking and heating and also by the unprecedented poverty, with more than 90% of people of Syria living below the poverty line, according to the United Nations.

Additionally, drivers like war activities, including bombing and shelling near the forested areas was a major contributor to the decline with more than 50% of deforestation occurring in areas with high intensity of explosive events.

In Yemen, a concerning and escalating trend of deforestation has emerged as a consequence of the surging demand for wood. This growing demand for timber and fuelwood poses a significant threat to Yemen’s prospects for sustainable long-term development. One of the key driving forces behind this disturbing trend is the intersection of heightened wood demand with the issue of high unemployment. Many individuals, particularly former farmers whose agricultural land has become unproductive, have resorted to logging as a means of livelihood and economic support.

The scale of this issue becomes even more alarming when we consider that approximately 886,000 trees are being felled each year to meet the wood requirements of bakeries and restaurants located solely within the capital city, Sanaa. This startling figure underscores the magnitude of the problem and its implications for both the local environment and the broader socio-economic landscape of Yemen. The indiscriminate harvesting of trees at such a rate not only threatens the country’s delicate ecosystems but also exacerbates the already critical issue of deforestation.

Saving the region’s forests

As we embark on a journey through the intricate tapestry of the SWANA forests, it becomes abundantly clear that their survival hangs in the balance. The enchanting argan groves, resilient cedar forests, and captivating mangroves that grace the coastlines all face an uncertain future. We must recognize the urgency of the situation and the shared responsibility we bear in safeguarding these precious ecosystems. Urgent actions are needed and they include:

Conservation and sustainable practices: At the heart of our collective efforts must be the unwavering commitment to conservation. Governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and local communities must unite to protect these forests. Sustainable logging practices, stringent enforcement of anti-deforestation laws, and the diligent restoration of degraded areas stand as vital steps toward ensuring the longevity of SWANA’s forests. It is incumbent upon us to balance our resource utilization with the need to preserve these natural wonders for generations to come.

Community engagement: Central to any successful conservation initiative is the active involvement of local communities. These communities often have deep-rooted connections to the forests, relying on them for their livelihoods. To mitigate the pressures driving deforestation, we must provide viable alternatives for income generation, education, and essential resources. By empowering these communities to become stewards of their own environments, we pave the way for sustainable coexistence.

International cooperation: Environmental challenges recognize no borders. To comprehensively address the multifaceted threats facing SWANA’s forests, international cooperation is imperative. Sharing knowledge, technology, and resources on a global scale can help combat deforestation and promote sustainable forestry practices. Collaborative efforts can also provide a united front against illegal logging and cross-border challenges that transcend individual nations.

Education and awareness: Raising awareness about the immense value of these forests is key to their protection. Through comprehensive education and passionate advocacy, we can instill a sense of responsibility and stewardship in the next generation. By teaching our children and communities about the ecological, economic, and cultural significance of these forests, we nurture a profound commitment to their preservation. Knowledge is the bedrock upon which sustainable change is built.

Preservation of cultural heritage: In recognizing the deep cultural and historical significance of these forests, we gain a more holistic understanding of their importance. Preserving the rich heritage intertwined with these natural wonders ensures that future generations grasp the intrinsic value of these ecosystems. It is not merely a matter of preserving trees; it is safeguarding the very essence of our collective identity and shared history.

If you want to read more articles and books, relevant resources and websites, you can find the author’s list here: