In the noisy center of Algiers, in a café near the Grande Poste, Medjeda Zouine and Nadjoua Rahem, journalists from Algeria’s first web radio Radio Voix de Femmes, introduce me to their daily work. Active since 1995, Radio Voix de Femmes is based at the Maison de la Presse, a symbolic place of the journalists’ resistance during the Algerian civil war, or the “Decénnie Noire”. Zouine and Rahem record in the Maison de la Presse’s studio and broadcast their work on YouTube. The name of the project signifies the intent: to take as much space as possible to report on the stories of women in Algeria.

The meeting with Medjeda and Nadjoua is only the first in what would be a month of research in Algiers, listening to the voices that populate the airwaves and web spaces. I am a guest in the house that once belonged to Mohamed Khadda (1930-1991), painter and militant of the independence movement, a space that is being transformed into a cultural centre and residence by the Rhizome gallery. The walls are lined still with some of the Khadda’s old posters promoting conferences and exhibitions such as the Day for the Preservation of Orality and the International Symposium on African Orality.

These posters take me back to Ici la voix de l’Algérie, Frantz Fanon’s text on the decisive role for the revolution of a particular form of orality, that of radio. During the years of colonization, Radio-Alger was a platform where ‘the French speak to the French’. The Algerian population, in their rejection of and disinterest in the voice of the colonizer, did not own any radio equipment until 1955-56. Then, in 1956, the turning point: on 16 December, with the announcement ‘here is the Radio of Free and Fighting Algeria,’ the clandestine radio inaugurated its broadcasting to the Algerian people. In less than 20 days all the devices sold out. Now one can finally hear ‘The Voice of free and fighting Algeria’. Broadcast from an unspecified place, it encounters the complicity of Egypt, Syria, and a network of Arab countries that rely on radio frequencies, avoiding sabotage of the airwaves by the colonial power.

Discontinuous and often interrupted, the radio liberated new languages, beginning to finally make the idea of an independent nation possible and true.

Radio Voix de Femme

From waves to podcast

Today, the Algerian government’s regulations on broadcasting both on the airwaves and on the web are demanding. Authorisations are so difficult to obtain that the number of private radio stations can be counted on one hand and, people commonly speak of radio as a state monopoly.

Yet new radio productions are born every week, circumventing government hurdles through podcasting and social media platforms. All it takes is a smartphone to record, and from that anyone can launch a new series on Instagram, YouTube, Soundcloud or Spotify.

On Instagram for example, the authors of Radio Voix de Femme, protagonists of the broad, plural and vibrant feminist movement, have recently launched Laha_podcast, a program outside their established radio format. They talk about the projects of Algerian women artists and their successes, but also about the violence or strong discrimination women endure, sanctioned by the Algerian Family Code, which still establishes de facto subordination of women to fathers, brothers or husbands. For example, in cases of divorce or inheritance, women are disadvantaged over their male counterparts.

‘Women’s voice is a revolution, as is that of all oppressed people,’ Besma Ait, author of the podcast Thawra (revolution), tells me. ‘Women’s voice is a revolution’ is a slogan from the Egyptian feminist movement that was shouted in the streets during the Arab Spring. It is a play on words, by changing a single letter in an old saying from the Muslim canonical oral tradition ‘the voice of women brings shame’. ‘Women’s voice is a revolution’ overturns this silencing old wisdom, symbolising the increasing voice of women’.

The Thawra podcast debuted in February 2024, driven by the need for feminist activists’ stories to be heard. The stories unfold through long conversations, removing the factor of time and urgency.

Its initiator, Besma, is part of a new generation of feminists trying to create continuity between struggles and maintain a dialogue between women who have experienced very different events: from the traumatic violence of Islamic terrorism, to the worsening changes in the Family Code, to the feminist fringe that marched every Friday for a little over a year during Hirak, the 2019 movement of democratic demands, which, after securing the resignation of President Bouteflika, was abruptly hit by arrests and violence until it was interrupted by the government in March 2020 with the advent of the pandemic.

Besma conveys to me the importance of this genealogy of struggles, which comes first and foremost from the women in her family. Her grandmother was a mujaheddine, part of the National Liberation Front (FLN) operating in France. ‘The story of exile is intertwined with that of the first anti-colonial struggle exported to enemy soil,’ she adds.

I follow her as she weaves the biography of her grandmother, who escaped from the Petite Roquette women’s prison in Paris, into the collection of stories recounted in the podcast episodes. The first episode tells the story of Fadila Boumendjel Chitour, an endocrinologist, human rights activist, and co-founder of Réseau Wassila, an important support network for women who suffer violence, based in Algiers. Madame Chitour comes to feminist consciousness through the practice of social medicine, treating the visible and invisible effects of violence and torture. Saadia Gacem, another of the interviewees, is also part of the Réseau Wassila, but is particularly involved in research on the Family Code and the treatment women receive in Algerian courts. Finally, Saadia carries out a valuable collective work, Archives des luttes des femmes en Algerie, because the history of such a powerful movement is still unwritten. Thawra itself fits into this same groove, as an artform that could be described as oral history.

‘Sound is the future of struggles’

Besma waves me off to join the feminist creation program, organized by the Journal Féministe Algérien, which founder Amel Hadjadj and trainer Khadidja Markemal will tell me about a few days later.

Khadidja is a refined and sharp sound artist, and in her works she manages to vividly render the sound images of a street or a neighborhood. At the end of our meeting, she hands me, on a USB stick, Sister with Transistors, a film about women pioneers of sound experimentation and electronic music. Some, like Daphne Oram or Delia Derbyshire, made radio history.

One of the recurring points in our conversations is the lack of female technical figures in the audiovisual world who can independently fabricate their own narrative. In response to this gap, the Journal Féministe Algérien‘s feminist content creation training program began in 2020, aimed at activists from various Algerian realities, groups, and collectives.

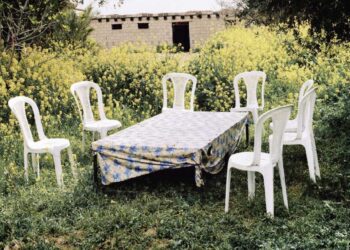

In the newspaper’s headquarters, a large flat overlooking the bay of Algiers, Amel Hadjadj shows me a room that can be transformed, if necessary, into a recording studio, soundproofed by mattresses. Stored inside a cupboard, all the material is available not only to the editorial staff, but to members of the public who need it for their projects.

‘Sound is the future of struggles,’ says Amel, as we discuss thickly. She finds in the discreteness of the recorder the perfect conditions to capture the words of women, often hesitant in the presence of a camera. Sound, whilst maintaining the subjectivity of each voice, protects those at risk, such as LGBTQIA+, from recognition.

‘In addition,’ she adds, ’the podcast is a form that allows women, for whom sitting in front of a screen is a luxury few can afford, to continue to inform themselves and listen to other women as they run between their housework and caring jobs.

At the end of this edition, the podcasts will be co-signed and will ‘belong’ to all participating feminist realities, for example the very young group Algerian Feminists. Initially an Instagram page created by Ouarda Souidi in 2019, it later became a full-fledged collective. Young Algerian Feminists want to contribute as part of the new generation to feminist struggles, reacting to the invisibility of women in society and the feminist movement’s initiatives. They publish monthly bulletins about actions in the country, speaking to as many women as possible through the creation of content mainly in darija.

They recently published their first podcast dedicated to menstruation, which is a social taboo in Algeria. The episode contains ten testimonies that hold together a polyphonic account of the turning point of menstruation in a girl’s life, a threshold crossed often without any preparation.

The blood on the thighs, the first explanation from the mother or the first attempt to wear a tampon, micro-memories followed by an awareness: menarche is a rite of passage. For some it is a ticket to the circle of women in the family gathered in the courtyard, to their confidences, to the possibility of shaving together, but for others it can also mark the beginning of dress injunctions, the change of looks, and new social norms. One of the voices reveals: ‘My mother told me to keep it a secret from my father, otherwise he wouldn’t let me play with my cousins anymore’

Listening to the real otherwise

Ouardia accurately translates these words to me through a series of voice messages and then adds: ‘Have you listened to Femmes sérieuses, travailleuses, non fumeuses yet?’

This is a sound documentary by Sonia Ahnou, an artist and filmmaker currently living in France. The documentary is an immersion in the life of a young woman who decides to live alone in Algiers. The title ironically takes up a recurrent formula in real estate advertisements.

‘What will the neighbors think of me, of the girl who lives alone on the third floor? I went to ask them with microphone in hand’.

This is how the story begins, bristling with many other experiences that portray the difficulty of achieving one’s independence even in the capital.

If oppression is systemic, it quickly becomes a business. The interviewees denounce the constant refusals to rent, or the abusive restrictions imposed, and even the rising rents for single women. ‘That’s also how you do segregation,’ closes one of them, in a firm voice.

Sonia has also passed through a strong network of militant realities that constitute the richness of the Algerian art scene. A key node is Habiba Djahanine, feminist filmmaker and poet, co-founder of the Cinéma-Mémoire collective. Since 2007, first in Bejaia and then in Timimoun in the Algerian desert, the collective has been accompanying young people for a year of training in documentary filmmaking.

All the people I met have a story that links them to Habiba and the ateliers, often an important turning point in their journey.

At the end of my residency, I invited Habiba, who is passing through Algiers, to share some of the sound creations from their rich archive. We are currently planning a collective listening session with a small circle of women with a sound project or who are building one.

What are feminisms if not a series of practices to break the silence, to listen to the self and the other?

So, at the beginning of the afternoon, sitting on the carpet of mon autre école, an important place for training and artistic creation, we immerse ourselves in listening to Mon peuple, les femmes. The author, Sara, stitches together fragments of intimate conversations between feminists – ‘Why are you a feminist? I don’t see why I shouldn’t be!”- or of a mother discussing with her daughter the choice to live alone, and again testimonies of actions against feminicide, and support for those who have suffered violence.

To free the word, anonymity is necessary. It is necessary to dare to tell of radical choices, such as the choice to no longer enter into any intimate relationships with men.

In 2021, the Cinéma-mémoire line-up abandoned the visual element to devote itself entirely to the soundscape.

We listen to the works, which, with a great variety of themes and artistic choices, take us to the oasis of Timimoun. Those by Assia Khemici and Lila Bouchenaf let us cross the threshold of female spaces, the liminal zones between inside and outside, between domestic and collective space. Without a trace of exoticism or voyeurism, no frame separates us from the landscape, we are inside with them.

In all the creations I have heard so far, the power of these voices and sounds resonates to question the hegemonic narratives of a purely ocular world, which leaves out anything that cannot be captured visually. Then the microphone becomes the possibility of breaking this imposed order, of contributing to a polyphonic rewriting, becoming again the subject of one’s own history. As Habiba tells us, after all, everything we do is a continuous attempt to transform the real in order to be able to look or listen to it otherwise.