This article was originally published by Ensia.

On a recent trek through Yemen’s Socotra island, local resident Issa al-Rumaili stops to point out a spot in the distance: “In front of us are the ruins of a vast forest of dragon blood trees,” he says.

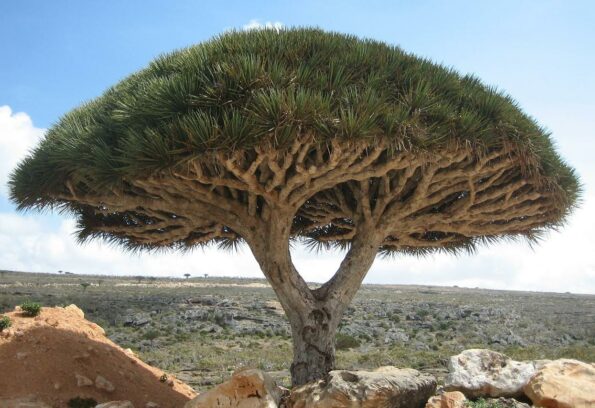

To see it requires some imagination. On an otherwise deserted hill stood three lonely trees, with their distinct umbrella-like canopies.

Dragon’s blood, or Dam al-Akhawain (two brothers’ blood), as it’s locally known, is endemic to Socotra, a mostly desert archipelago south of the Arabian Peninsula, whose isolation from Yemen’s mainland has largely spared it the destruction of the country’s nine-year civil war and preserved its distinctive nature.

Due to the scale of the diminishing population of the dragon’s blood trees, it is listed as a vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List. Photo by Boris Khvostichenko, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

But international and government funding for Socotra’s environmental protection authority has dried up, and financial support previously offered to native efforts to save the tree has dwindled, says the authority’s director Salem Hawash.

This funding reduction isn’t completely due to the ongoing conflict, according to a 2021 report from the Conflict and Environment Observatory, a charity based in the UK. “The problems pre-date the current conflict,” the report reads. “By 2012, the IUCN reported that the Socotra EPA’s annual budget was just US$5,000.”

That said, the report goes on: “It appears inevitable that the intensifying pressures that the islands are facing as they are dragged into the conflict will continue to place their unique natural and social heritage at risk.” Meanwhile, the authority’s building was converted by Saudi military forces into a temporary headquarters, according to Socotra residents — a reflection of the war’s impact on the island, and the further sidelining of its biodiversity.

These hurdles, along with those brought about by a changing climate, contribute to the uncertain future for the dragon’s blood tree. “I’m afraid this may be the last generation of this amazing tree,” says Hawash. In the face of this uncertainty, many of the island’s residents are working to protect the tree and make sure it does indeed have a future on the island.

A priceless lifeline

The Socotra archipelago, one of the most biologically diverse places on Earth, was classified a UNESCO Natural World Heritage site in 2008, but is now facing ecological devastation as a result of climate change and human activity. Populations of the dragon’s blood tree — which is at the heart of the island’s unique flora and fauna and part of Socotra’s identity that sets its people apart from the rest of Yemen and the region — are in frightening decline.

The effects of climate change, including increasing frequency, duration, and intensity of cyclonic storms, and overgrazing and harvesting of the tree’s deep-red resin, which is popular for medicinal purposes, cut the tree’s density by 44% in the 20th century. And while it is estimated that the tree only covers 5% of its potential habitat, scientists expect drier conditions to slash it by another 45% by 2080.

“The loss of one dragon blood tree means the loss of tourists, of water, of medication, and — what is worse — the loss of the Soqotri identity,” says Kay Van Damme, a conservation biologist who has been involved in Socotra conservation since 1999.

In response to these challenges, a local community on secluded Socotra Island at the periphery of a country that was the poorest nation in the Middle East and North Africa long before it became “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis” is trying to keep the coveted tree from going extinct. Currently it is listed as a vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List.

While a power struggle continues in Yemen between parties involved in the ongoing conflict, flights linking Abu Dhabi and Socotra still bring in adventurous visitors keen to enjoy the island’s magical landscape and its unique tree.

In an archipelago where most of the people live below the poverty line and job opportunities are rare, ecotourism is a priceless lifeline. Tourists visiting the archipelago increased from less than 200 in 2001 to more than 3,700 in 2010. While the island did see a decline in visitors after 2010 due to political unrest and security concerns, last year, roughly 5,000 tourists visited Socotra, tourism ministry officials say.

“Tourists from all around the world come to our remote villages to spend days among these trees,” says al-Rumaili. “If we lose this, what will become of us?”

Biodiversity linchpin

Efforts to save the dragon’s blood tree began 27 years ago when Adeeb Abdullah, who is now in his 80s, started a plant nursery in the backyard of his home near Hadibu, a small coastal town on Socotra. Serving as a haven for seedlings to grow without being grazed or harvested, the nursery was the first community initiative to preserve endemic and endangered plants on the archipelago.

Adeeb Abdullah’s nursery serves as a haven for dragon’s blood seedlings to grow without being grazed or harvested. Photo by Abdumalik Alnemri.

Since then, a handful of other initiatives have sprung up to protect the dragon’s blood tree. One has managed to grow as many as 600 saplings over the past 20 years.

Van Damme says there are currently more than 80,000 dragon’s blood trees, which can live for hundreds of years. But they’re mostly very old, while younger ones rarely survive.

According to researchers, the dragon blood tree’s canopy shades and provides water to other rare plants that grow around it, capturing moisture equivalent to more than 40% of the island’s annual precipitation. The tree is therefore pivotal to the biodiversity of Socotra, where 37% of the plants and 90% of the reptiles are endemic.

Where the trees belong

Abdullah’s nursery now attracts visitors from all over the world. “They come to the nursery for these rare plants, especially dragon blood seedlings, taking pictures for research or memories,” Abdullah says. “This way, the tour guide, the car driver, the hotel owner and I benefit. The unique biodiversity and amazing scenery attract tourists. But if this disappears, no one will come to us.”

Dragon’s blood trees have distinct umbrella-like canopies that shade and provide water to other rare plants that grow around them. Photo by Abdulmalik Alnemri

Returns from tourism help Socotra’s inhabitants afford essential services often unavailable on the island. While regional players involved in the war construct schools and medical units and provide electricity as part of development plans in which they compete for control over the strategic island, utilities on Socotra remain scarce. For instance, Abdullah’s wife and children still need to make daily trips to distant wells to fetch drinking water, as well as gather firewood to be able to cook.

Ahmed Fathi, a local photographer, says Socotra’s inhabitants still need to travel outside the island for medical treatment, employment and studying. “This is two or three days at sea, or a weekly flight that is too pricey for most.” The island is still “marginalized and isolated,” he says.

The dragon’s blood tree and the biodiversity it fosters are widely seen by many in Socotra as their link to the world beyond through tourism and general international interest.

The decline in government funding makes local initiatives like Abdullah’s even more critical.

Despite his efforts to save the dragon blood trees, Abdullah remains anxious about the future. He worries his children won’t be able to move the trees to the mountainous habitat outside the nursery’s confines.