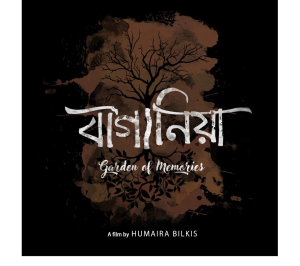

Released in 2019, the film Baganiya (n. বাগানিয়া, people of the tea gardens, tea garden workers), in English Garden of Memories, by Humaira Bilkis came to Cinelogue’s film library at a time of great political upheaval in Bangladesh in July 2024.

The student uprising that ousted Bangladesh’s fascist prime minister cum dictator Sheikh Hassina on 5 August 2024 has continued to articulate its aims in terms of abolishing inequalities based on any and all forms of discrimination. While an interim government has been formed and includes representatives of, for example, the student movements, civil society organisations and some Indigenous communities from the Chittagong Hill Tracts, representation for Bangladesh’s tea garden workers, remains absent.

Watching Baganiya, we understand why. The film deals with the 150-year-old inequalities of tea garden workers (self-titled as baganiya) labouring in the Champarai tea estate in the Moulvibazar division of Sylhet, a north-eastern region of Bangladesh.

Colonial oppression

The tea garden workers were brought here from other parts of India in the 1800s by British imperialists and local middlemen. Originally under the British East India Company, Champarai now belongs to the state owned National Tea Company Limited under the chairmanship of Sheikh Kabir Hossein, a relative of the now ousted but active Sheikh Hassina.

Though Baganiya precedes today’s revolutionary Bangladesh, its scenes and the communities it represents bear the marks of abuse, neglect and continued colonialism which Bangladesh’s student body is currently, and most visibly, challenging. While the movement was triggered by protests against government job quotas, youth unemployment and middle class wealth disparity, the call for an end to a fascist state not only tackles the dictatorial rule of Sheikh Hassina and the Awami League, but also challenges the state apparatus in the way it has functioned since Bangladesh’s independence in 1971.

The messages being chanted and painted across the country and diaspora remain clear: the freedom of some cannot be sustainably built on the oppression of another.

Baganiya offers a specific but important position to consider in this moment of social and political change. The colonial oppression of tea garden workers in the country necessarily must be part of the change the revolutionary part of Bangladesh’s population wishes to make. To do this, it is necessary to consider the ways the state relates to these communities and society at large.

The making of a film

Documentary films about tea communities in Bangladesh are a popular focus for Dhaka-based filmmakers, artists, ethnographers and academics, with many being screened locally at middle class institutions and universities in the capital. Humaira Bilkis’ oeuvre joins this canon.

I first watched Baganiya in 2019 at the Goethe Institute in Dhaka, a space nestled in the older upper class district of Dhanmondi and a popular space for cultural events visited by local middle class and foreign patrons. The film is remarkable in its use of sound, allowing for minimally edited soundscapes of the natural environment in which the tea trees thrive and the communities labour and live.

Bilkis makes a point not to over explain, or to provide an overly probing narrative, but rather follows the people she has chosen to focus on, like Padmaluv Bunarjee and Sojoy Yadav, who both answer questions and at other times just allow the camera to join them through their days and thoughts.

On the one hand, this offers a sense of the tea communities from within their homes, at work in the tea gardens, and over adda (chat, conversation) between duties. But given the asymmetrical power dynamics between the filmmakers—who are ethnically Bangali, of the Muslim majority, educated, middle or upper class, and based in the state capital—and the tea workers, the absence of the filmmakers in Baganiya left me with a sense of unease. Why did they come to the tea gardens? Why then? How did they negotiate their access? How did they nurture their relationships with their interlocutors?

Bilkis describes the way her relationships to her interlocutors developed: “I first came to the tea gardens to make a workshop film that was partly facilitated by an NGO around 2007. I had no intention of making a film.” She was just spending time in the community and slowly their relationship developed.

“I started making the film much later, in 2015,” she recalls. “I initially wanted to make the film about a young orphan girl who was living in the village on her own, and who was supported by everyone, this was really remarkable for me. But I ended up going to India for a year and when I came back she had fallen in love and left the village.” After that, the subject of her film somehow shifted. “I have most contact with Sojoy, he is very active and politically astute, working in the tea garden labour union himself,” Bilkis explains.

The focus on Sojoy is palpable in the film—he gives us the political context of the space the film is navigating.

Asymmetrical relationships

The unequal social positioning of Bilkis and the tea garden workers and how this affects their relationships are emblematic of the relations of patronage that develop between people of different classes in South Asia working and/or living together. “When the tea garden workers were on strike a few years ago, they were fighting for a 300 Taka minimum wage (EUR 2.30). Sojoy called me during that time and said ‘we need food’. So we put money together and sent them food so they could continue to live. They only reached a 170 Taka minimum wage (EUR 1.30).”

For Chandon, a teenage boy avoiding school and whom the film follows mostly through his roaming in the tea gardens, Bilkis and her film crew were actively involved in his future building. “We paid for his college fees, but finally he didn’t go. He works now: we really wanted him to be able to finish school. This is really sad for me.”

Bilkis is well aware of the asymmetrical relationships and how they are necessary both to support Sojoy, Chandon and the tea garden communities, as well as to provide her subject matter as a filmmaker. Like many in Bangladesh, as the student movement has also shown, she is aware that these relationships do not sustainably ensure the autonomy of those oppressed by state and structural violence. Especially given the historical, colonial nature of the oppression of tea garden communities in Bangladesh, more than social awareness, structural change through state policy is necessary to ensure sustainable change.

Having spent time in Sylhet through friends who have generational ownership of tea gardens or family members who are managing them, I have been part of the power structures that hold up the inequalities I lay out here. Many people escape Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka to Sylhet in order to enjoy time in nature and away from the city. Sylhet is teeming with eco lodges, bed and breakfasts, and large scale resorts catering to domestic tourists, who drive or hike through the tea gardens. What for some is a place of generational oppression becomes a leisurely escape from city life to another.

“The community in Baganiya is far removed from the dominant tourist trails, though many come to visit the waterfalls close by,” Bilkis describes. People trying to capitalise on the touristic potential of the area come from outside the tea garden communities and are met with resistance. “Sojoy is one of the biggest fighters against building tourist infrastructure in their area. Once a man came from outside trying to convince him that they should build housing for tourists. I was standing on the side with my bags and the man pointed at me and said ‘Look, she has nowhere to stay, if there was housing she could stay there.’ Sojoy laughed and said ‘She’s staying at my place.’”

A struggle for equality

Sylhet distinguishes itself economically and linguistically from the rest of the country. While the language spoken in the area, Sylheti, is considered by some to be a dialect of Bangla, the national language of Bangladesh, it has a different script and many locals and people in the diaspora argue for Sylheti to be recognised as its own language. The region is also known to be wealthy due to the high remittances sent to communities there from abroad, particularly the UK. Nestled within this region, the tea gardens form a microcosm of isolation not only nationally but regionally also.

This isolation is central to Baganiya. In the first minutes of the film, Sojoy tells us that the British brought or coerced people from different parts of India to the tea gardens that are now in Bangladesh. These people came from vastly different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, so there was little possibility to unite against their shared oppressors. Bringing communities thousands of miles from their original homes, and further alienating them by denying them land rights or access to social development, left the tea garden communities isolated both from their land, their labour and each other.

In the context of the revolutionary moment in Bangladesh today, Baganiya inadvertently presents an important question: how can Bangladesh develop equality intersectionally across socio-economic strata, genders, religions and ethnic communities? In retaliation for its downfall, the Awami League has instigated violence against Hindu and other religious minorities (though partly this violence is also ‘organic’). The student movement remarkably responded by protecting non-Muslim religious sites, homes and businesses. These are scenes until now unseen in South Asia at this scale.

The Awami League’s actions show that religious-based violence remains a potential instrument to destabilise community and state. But the actions, art and organising potential of the students and their supporters tell a new story and project a different kind of future. A dismantling of existing power structures should necessarily entail a new beginning for tea garden workers also, no longer defined by their labour alone and state-sanctioned impoverishment, remembered through elite holidays in the tea gardens or film viewings in the city. This, however, is unlikely.

Asked if the student movement is providing momentum for change for the tea garden communities, Bilkis responds with a bleak outlook. “Unfortunately, I don’t think there is going to be any change for tea garden workers now. The government has been saying for years now that the tea gardens aren’t economically viable.” While their labour has been their yoke for generations, the tea garden workers are also reliant on his labour for their income. Without it, and in the modus operandi of successive and current Bangladeshi governments, they may lose all leverage in their struggle for equality.

BAGANIYA is available for global streaming on Cinelogue– a collaboratively curated streaming platform dedicated to cinema by the Global Majority.