Whatever the outcome, it is remarkable what has transpired in Bangladesh since mid-July. What started as a student movement to reform the “quota” system in universities and government employment, turned into a full-fledged mass movement within a week. The “quota” system is an affirmative action to ensure that different marginalized sections of society receive equitable opportunities and representation. The particular quota which triggered the student movement is the 30% reservation of all government and university jobs for family members of fighters of the Bangladesh Liberation War.

In practice, this quota has been used predominantly by the ruling Awami League to benefit their own supporters. The Awami League, one of the major political parties and one of the protagonists of the independence struggle, had ruled in an authoritarian manner for a decade under the premiership of Sheikh Hasina, the daughter of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the ‘founding father’ of modern Bangladesh.

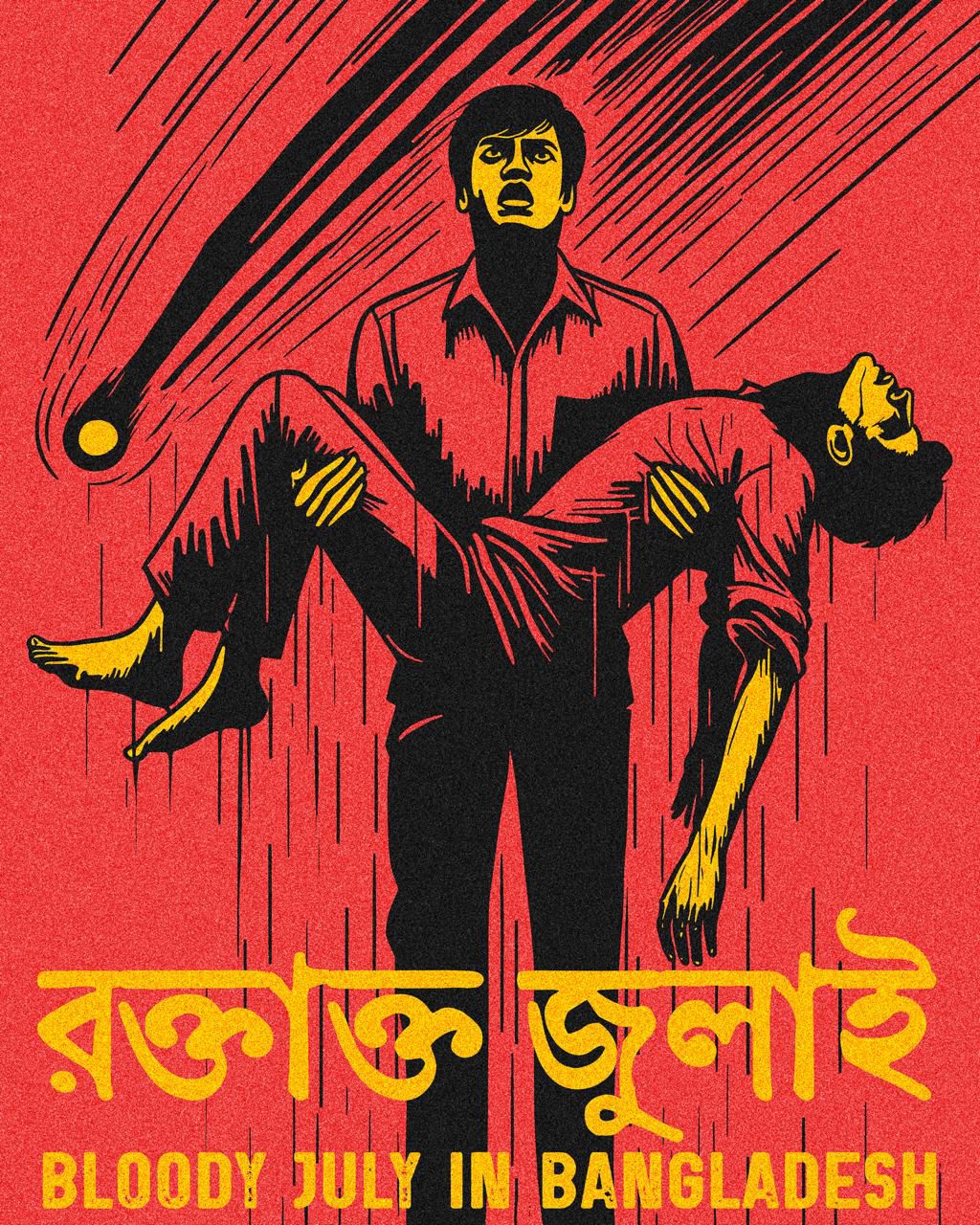

After the protests erupted, Hasina met the students with unprecedented force, first with her private political militia and then the state forces, resulting in the death of hundreds of demonstrators. The sheer cruelty of the response led to widespread anger and waves of protest across the country.

Sheikh Hasina’s government had faced protests before and consistently resorted to violent suppression. This time, violence proved not to be enough: what began as a student movement in mid-July grew by the first week of August into a widespread people’s revolt, culminating in millions marching to the capital Dhaka, and ultimately forcing the Prime Minister to resign and flee the country.

A revolution long in the making

As it is often the case, revolutions begin from the simplest demands or a ‘small incident’, and this was no exception. For over a decade, Bangladesh languished under an autocratic regime – democratic processes were strangled, dissenters were forced into exile or killed, elections were rigged, and, most importantly, the country became a key site for neoliberal capitalist exploitation.

Socio-economic indexes often tell us an opposite story of reality. According to the World Bank, Bangladesh “tells a remarkable story,” elevating itself from one of the poorest countries in the world to a middle-income country.

But, as it often happens, data can be deceiving. One of the major developments is that the country has become the textile hub of the world since the early 2000s. In fact, it is likely that you are reading this text while wearing a t-shirt produced in Bangladesh. Textile production reached its peak in the last decade. According to the local Export Promotion Bureau data, in the fiscal year of 2021-22, Bangladesh exported garments worth $42.613 billion, making it the second largest apparel exporter in the world.

While this meant more wealth in the hands of the capitalist class, the socio-economic situation of workers hardly changed. Thousands of workers died in different accidents in the factories in the last 15 years, as they hardly enjoyed any labor rights and their wages remained stagnant. With almost 85% of the workforce in informal employment, the socio-economic conditions of many in the country have not seen the kind of development described by macrotrends.

In addition, even though Bangladesh’s GDP growth remained relatively high among developing nations, it largely remained an importing country. Beyond textiles, Bangladesh’s largest export is human capital. Approximately 7.4 million Bangladeshis live abroad, making the country the sixth largest in terms of out-migration globally. The Bangladeshi diaspora, often composed of workers living overseas with limited or no labor rights—and in some cases, without legal documentation—remains a critical financial lifeline for the nation. Each year, they send home $21 billion in remittances, a large segment of Bangladesh’s economy.

Under Sheikh Hasina’s regime, the neoliberal exploitation of natural resources intensified, with the Sundarbans and the Chittagong Hill Tracts becoming major sites of primitive accumulation. Sundarban recently became a site for the most important power plant project in Bangladesh’s recent history, endangering the diverse flora and fauna of the UNESCO heritage site. On the other hand, Chittagong Hill Tracts became the site for uncheckered mining, endangering nature and the indigenous communities living there.

The role of India

The nature of the current protests, like Bangladesh’s political economy, cannot be fully understood without considering the role of India. The India-Bangladesh relationship is historically complex. Bangladesh was once part of British India and became the eastern province of Pakistan after the partition of 1947. India played a crucial role in Bangladesh’s liberation, hosting the exiled government and ten million refugees, and ultimately assisting the Bangladesh Liberation Army in defeating Pakistan in 1971.

In the years that followed, India remained a close ally of the Awami League, first during Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s regime (1971-75) and then Sheikh Hasina’s (1996-2001 and 2009-2024). In between, Indo-Bangladesh relations experienced ups and downs.

What is significant in relation to the July uprising is India’s increasing hegemonic role in Bangladesh’s political economy. Indeed, several infrastructural projects, heavy industries, and a large portion of the Bangladeshi market is under the control of Indian capitalists. A large number of Bangladeshis visit India for healthcare, education, and other reasons, even if the visa regime has become harder over time. This growing influence of the Indian capitalist class in Bangladesh accelerated under Sheikh Hasina’s regime, in exchange for strategic support from the Indian government.

Sheikh Hasina’s government increasingly came to be seen as a satellite establishment of India, fueling widespread anti-India sentiment, which became a crucial component of the July Movement. Anti-India slogans and posters were ubiquitously present in the demonstrations, following several calls to boycott Indian goods since last year. The growing tension in India against minorities (especially Muslims) under the Hindu nationalist regime also contributed to the anti-India sentiments.

Troubled past

During the last decade of Hasina’s rule, there was an unprecedented attack on democratic values and procedures. Opposition parties became almost non-existent, with the opposition leader of the right-wing Bangladesh Nationalist Party, Khaleda Zia, placed under house arrest for years. There are claims that the 2018 and 2024 elections were blatantly rigged by the Awami League. Civil society opposition, as well as alternative social and political movements, were brutally suppressed by the police, secret police, and army. Kidnappings, extrajudicial killings, and illegal detentions became everyday occurrences in Bangladesh. Thousands were either killed or imprisoned or forced into exile. No one was spared: intellectuals, journalists, political activists, indigenous rights activists, and climate activists, all faced the same fate.

Sheikh Hasina’s authoritarian government has maintained its grip on power in Bangladesh not only through the use of violence but also by cultivating a political and historical consensus among the country’s secular and cultural elite. The recent events, and more broadly, the regime of Sheikh Hasina, must be understood within the context of Bangladesh’s history and the ideological battles that have unfolded since 1971.

Though Hasina had little democratic legitimacy, she wielded a certain cultural and ideological authority. Bangladesh has a troubled history and is still grappling with the legacy of the 1971 liberation war. During that war, Awami League and the left parties largely led the struggle against the Pakistani army while Islamist forces acted as collaborators of the Junta, actively participating in the genocide, mass-rape, and other crimes against humanity.

Until 2006, the period from the 1975 assassination of Mujibur Rahman, the leader of the Liberation Movement and the first president – save for the brief period of Sheikh Hasina’s premiership in the late 1990s – is largely perceived as a reversal of many ideals of Bangladesh’s liberation. Linguistic nationalism, secularism, and socialism were abandoned, and the war criminals of 1971 not only roamed freely but became part of the ruling coalition.

In fact, after the assassination, the collaborators with the Pakistani regime during the liberation war, Jamat-i-Islami, were not only reinstalled by the military government but eventually became part of the government led by Khaleda Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) between 2001 and 2006.

Though BNP’s founder Ziaur Rahman was a decorated hero of the liberation war, it was during his military regime that Islamists were handed over the opportunity to return to mainstream politics.

Therefore, when Sheikh Hasina returned to power in 2009, she had a mandate to complete the ‘unfinished liberation’- punishing the collaborators and assassins of her father, Mujibur Rahman.

2013 marked the height of post-independence Bengali nationalism, when thousands of students and civilians took to the streets to ensure justice for the 1971 war criminals. Though it was a civil society movement in every sense, Hasina was the ultimate beneficiary, as it provided her with impunity rooted in her father’s legacy and the Awami League’s role in Bangladesh’s liberation. Hasina capitalized on this by converting the cultural-historical legacy into a political license to silence all opposition, labeling them as anti-liberation forces when necessary. Practically, anyone questioning her authority was automatically branded a traitor to the legacy of liberation.

At the same time, though Hasina crushed Jamat-i-Islami as a political entity, she did little to stop the increasing Islamization of the country. In fact, she made a tactical alliance with Islamists, allowing them to indoctrinate thousands and alter the social fabric, as long as they did not challenge her political authority. In simpler terms, she allowed Islamists to operate freely within limited political sovereignty, even letting them infiltrate the Awami League’s ranks. Meanwhile, she maintained the façade of being a secular leader, acting as the protector of minorities and liberal culture, without whom Bangladesh would supposedly become an Islamist state.

Glimpses of hope in an uncertain future

The larger question that now looms after the collapse of the tyrannical Hasina regime is: in which direction will Bangladesh go? The student movement, which forms the core of the protests, is not a homogenous political force. It lacks organizational structure, political vision, and most importantly, an ideological framework.

The broad-based, grassroots open alliance that was the strength of the movement could quickly become its weakness unless a progressive political party with a clear agenda emerges, or the existing progressive leftist forces are able to guide the movement in the future, which so far does not look likely.

In the aftermath of Hasina’s government’s collapse, Islamist forces began wreaking havoc across the country, attacking minorities, destroying “anti-Islamic” sculptures, and toppling statues of Mujibur Rahman. However, the Islamist forces were met with resistance. The progressive section of the movement and common people intervened to stop them together with minority communities. While these actions provide hope that Bangladesh might not fall into another tyranny, Islamists and the right-wing Bangladesh Nationalist Party remain the strongest organized political forces at the moment.

If there were a free election tomorrow, they would likely win a majority of the seats.

Another important factor in the future of the country is the role of the United States. We still don’t know whether the US or its allies played a role in supporting the anti government protests, but what is certain is that the regime change plays in favor of the US strategic vision in South Asia. The interim government formed after rounds of negotiation between the army and the protesters is being led by Muhammad Yunus, a Nobel laureate economist, who has close ties with the US establishment. Hasina’s government, because of several historical reasons and geopolitical compulsions, was averse to the US, becoming increasingly close to China.

At this moment, there are two competing geostrategic projects that are becoming instrumental in navigating diplomatic relations in South and South-East Asia. The first one is China’s Belt and Road initiative, which would invest $40 Billion in Bangladesh reflecting the growing influence China has in the country. The second project is the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) which tried to include Bangladesh in an anti-China alliance. Hasina was cautious and refused to get on board with a blatant anti-China military collaboration. This scenario is likely to change under the new regime, which is already showing more willingness to cooperate with the West.

In this context, the lack of strong leftist and socialist forces that could have given this movement a more progressive direction is unfortunate. What is needed today is a new progressive political force that could break the cycle of tyranny that has marked the country’s post-independence history to ensure peace, justice, and democracy for all working classes, minorities, and every segment of society.

However, this does not mean the current movement itself is reactionary. Bangladesh’s working people and democratic public have endured an immensely repressive phase over the last decade. The July Revolution has brought an end to an authoritarian regime, and this achievement deserves recognition and celebration.

The most important decision that the interim government has to make at the moment is when and how they are going to conduct the next election. It is difficult to predict when, but the legitimacy that this government earned through the “revolution” has its own expiry date. Until now, the government has not come up with a concrete roadmap for handing over the power to an elected cabinet. The hope and the relief that came with the change in government will quickly transform into frustration and anger unless the interim government finds a way to ensure a peaceful transition of power to the hands of elected representatives.

It has been more than a week since the interim government has taken over and the political situation is stabilizing in Bangladesh. The institutions of the state, like the army, judiciary, and the bureaucracy, have not seen any radical reform yet, which can be an indication that the “revolution” has not brought any fundamental change, especially within the state apparatus and the political economy. Unless the interim government succeeds in bringing meaningful changes in the lives of the working classes and addressing the social and economic issues of the majority of Bangladeshis, one may expect there can be another round of protests and growing peoples’ movement and that could be decisive for Bangladesh’s fate. One can only hope that the young generation and the working class who inspired the July movement will soon emerge as a progressive political force that will guide the real changes in Bangladesh.