Brazilian Luan da Silva, 33, spends his Mondays offline. He wakes up, has breakfast, washes his hair, goes to the gym, organizes the week’s video schedule according to contracts, sits in the yard, and writes ideas.

From Tuesday onwards, he prepares, sets up equipment, records videos, edits and distributes them, monitors their reception, and responds to interactions. In between, he keeps up with global trends to innovate constantly and meet platform demands.

“I call myself a multi-artist to encompass more possibilities, but for 4 years, I’ve worked online as a digital influencer,” he says. Known in Belo Horizonte, capital of the country’s southeastern Minas Gerais state, as @alomarilu, Luan gives travel, beauty and fashion tips, as well as reflections on life, recipes, and the daily routines of his pets. In practice, he works on and for digital platforms, mainly Instagram, which he calls “my mini reality show”.

Digital influencers like him are part of a broader context that researchers call the platformization of work. This global phenomenon impacts various sectors of the digital economy, introducing information and communication technologies into work relationships, thereby controlling and generating service delivery.

“This dynamic is observed in various sectors, such as delivery and ride-sharing services,” explains Nina Desgranges, a Brazilian social scientist and researcher at the Institute of Technology and Society (ITS). “Content creators who bring forth or hope to bring forth income through platforms like YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitch can be classified as platform workers and, more specifically, as cultural workers in the platform economy,” she adds.

All digital platform work has a similar contradictory nature, including influencers: on one hand, the promise of flexibility and autonomy; on the other, working conditions that deviate from formal employment relationships, transferring any risks to the workers. This nature raises important issues related to labor rights and the regulation of these platforms and the work they facilitate.

Despite the common perception that influencers are paid to do something easy, lucrative, and enjoyable, their work routine is often marked by uncertainty, irregular pay, fluctuating follower counts, and compromised mental health.

Flávia Pinho, another influencer based in Belo Horizonte explains that digital content creation “is a very complete and complex work.”

Flávia got into the digital content creation business in 2015 to promote her makeup work: “I started with photos of clients, but as there was no demand I ended up putting on a lot of makeup. I realized that this type of content brought me more engagement and I started to explore this side.”

For her, “the big challenge is to create a connection with the public in order to reach a place of influence and achieve tangible financial returns. This takes time and dedication.”

“It seems simple, but it involves many steps and, for the most part, we need to master many areas, photography, editing, script development, client prospecting, in addition to the charisma that has to appear without a shadow of a doubt,” she adds.

Her success on digital platforms – with over 160,000 followers on her Instagram account @__flaviapinho – allowed her to open her own beauty salon called Glow in 2020. “I am currently dedicating much more of my time and energy to Glow considering the challenges of a new company on the market, but my goal is to return with my content in a more professional way,” she says.

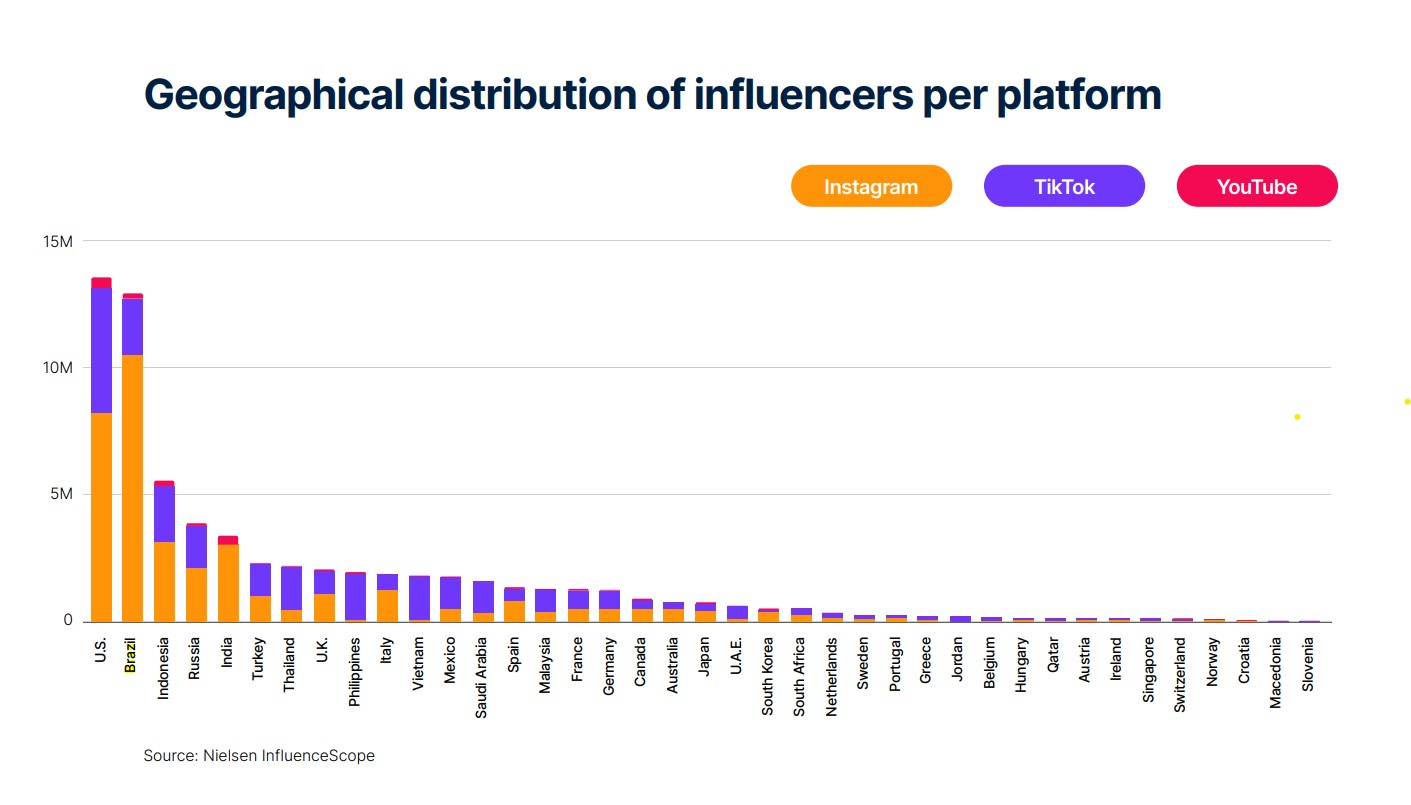

Brazil tops the list of countries with Instagram influencers, with over 10.5 million users, according to annual studies by Nielsen. On TikTok and YouTube, Brazil ranks second, behind only the United States.

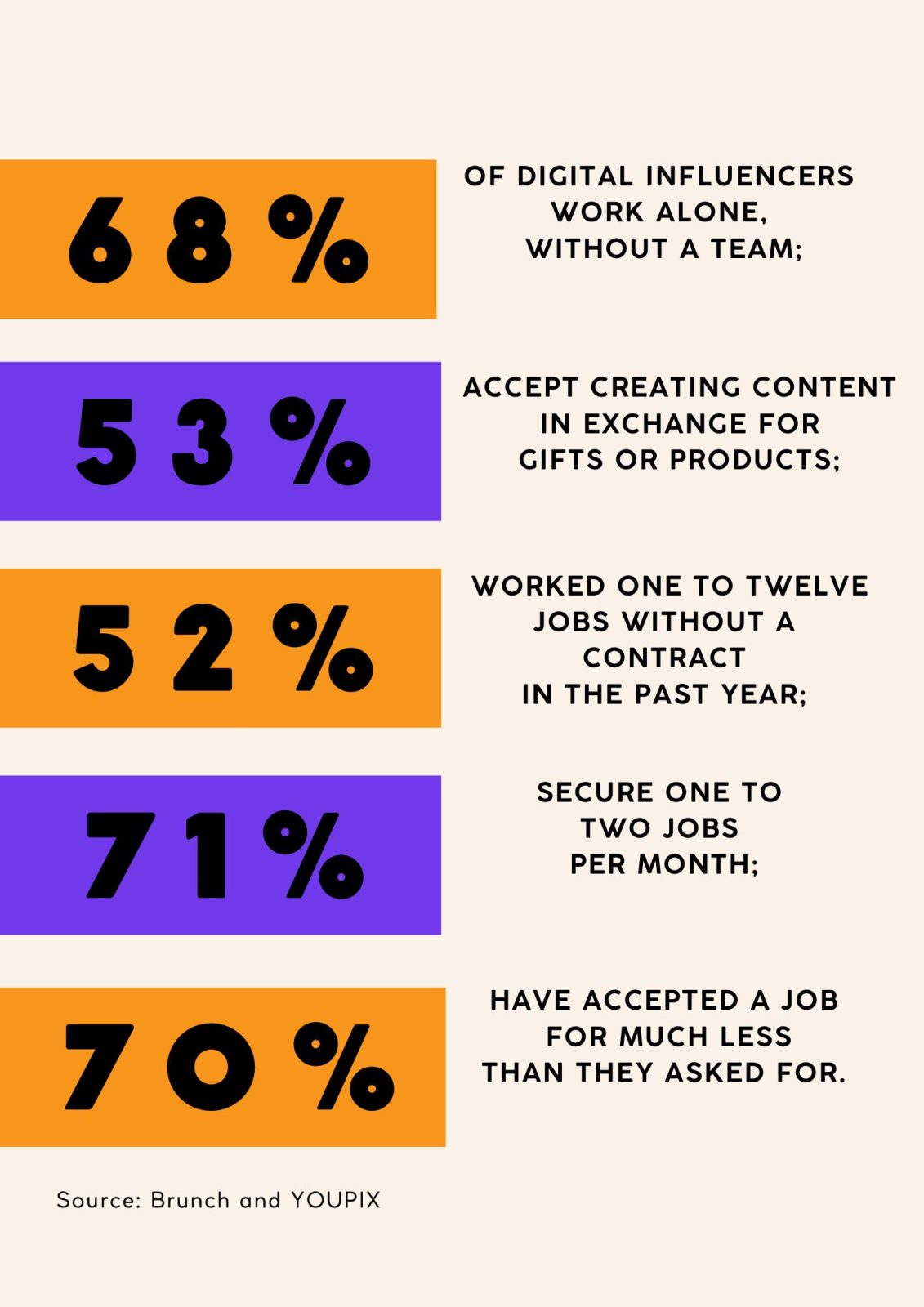

Given the large number of influencers, working conditions need careful consideration: over 68% of digital influencers in Brazil work alone, without a team; 53% accept creating content in exchange for gifts or products; 52% worked one to twelve jobs without a contract in the past year; 71% secure one to two jobs per month; 70% have accepted a job for much less than they asked for. These figures come from the Creators & Business survey, a partnership between Brunch and YOUPIX companies.

“It’s work without pay, done in the expectation of making it. In this case, you work imagining that one day you will be an influencer who lives entirely from the income of influence. Until that moment arrives, you work for free for the platforms,” explains Issaaf Karhawi, professor at Universidade Paulista with a Ph.D. in Communication Sciences from the School of Communication and Arts at the University of São Paulo.

Given these dynamics, platformized work is created without ethical and regulatory precedents in one of the most content-producing and audience-influencing countries in the world. While some countries have initial experiences of regulation, Brazil is beginning to discuss its solutions.

The debate about solutions and platform work regulation often focuses on delivery drivers and app-based drivers, but according to experts influencers should also be included in this long conversation.

Luan sees positive impacts in regulation and the debate it foments. “We are discussing what the work is and what it will become, given AI, for example… I think it’s important to regulate because of market saturation and the need for future security, even considering retirement,” he says.

For Flavia, the debate about regulating platforms is very important but there needs to be a balance: “I imagine that regulation can help guarantee some benefits, bring a little more transparency, financial protection, but it is important that these rules do not stifle creative freedom or make things too bureaucratic. It would make life very difficult, especially for small creators.”

Recognizing content creation as a profession and regulating it can not only legitimize the work but also open doors to essential protections and rights, leading to the development of ethical codes applied to the category, all to prevent the silent precarization of influencers’ work.

For Issaaf Karhawi, demands should start with transparency. “There are many discussions about monetization, of course, but… the essential thing is transparency in the relationship with platforms because influencers report not fully understanding how they work,” she explains.

Platforms often do not disclose how algorithms work, affecting the visibility of influencers’ content without their knowledge. Moreover, they collect vast amounts of data on influencers and their followers but do not always clarify how this data is used or shared.

Nina Desgranges, a researcher at the Institute of Technology and Society in Rio de Janeiro, highlights another item on the content creators’ list of demands for regulation: “policies that protect influencers’ intellectual property and provide mechanisms to resolve contractual disputes.”

In Brazil, where union culture has deep roots, association should also be considered an important topic in strengthening the Creator Economy. “Collaboration between influencers, unions, civil society organizations, and legislators can be crucial for developing effective policies that protect digital workers’ rights and interests,” Desgranges emphasizes.

Brazilian laws need to evolve alongside digital transformation. The process of the Bill 2630/2020 started in 2020, when it was presented and debated by the Brazilian Congress.

The bill creates the Brazilian Internet Freedom, Responsibility, and Transparency Law and proposes regulating digital platforms like Google, Meta (Instagram and Facebook), X (formerly Twitter), and TikTok, in addition to instant messaging services like WhatsApp and Telegram. The proposal has caused significant political instability and public lobbying movements among big tech.

The bill does not solely concern creators; it is broader and focuses mainly on controlling the spread of false information and hate speech online. The idea is to hold platforms accountable so that accounts or posts with criminal content can be more easily identified, removed, or flagged.

One key proposal is holding companies responsible for content published by third parties. Currently, there is no Brazilian law allowing their punishment in case of offensive or criminal content on their platforms.

Although not focused on creators, the bill promotes public debate and an environment filled with new ideas. Despite being processed under urgency, the bill has been stalled in the Brazilian Congress for a year.

For public debate to advance, legislators and society can use public consultation as a vital tool to understand the needs of content production professionals for and on platforms.

Collaboration between legislators and the creator community is key to effective and adaptable regulation, which, when done collectively and with concern, can promote a creative, healthy, and prosperous ecosystem.

“I believe it is possible for our lives to be transformed by this profession. But beyond the specialists, we, and especially Gen Z, need to be heard as well and commit to this debate”, opines Luan, while producing his “mini reality show” on Instagram.