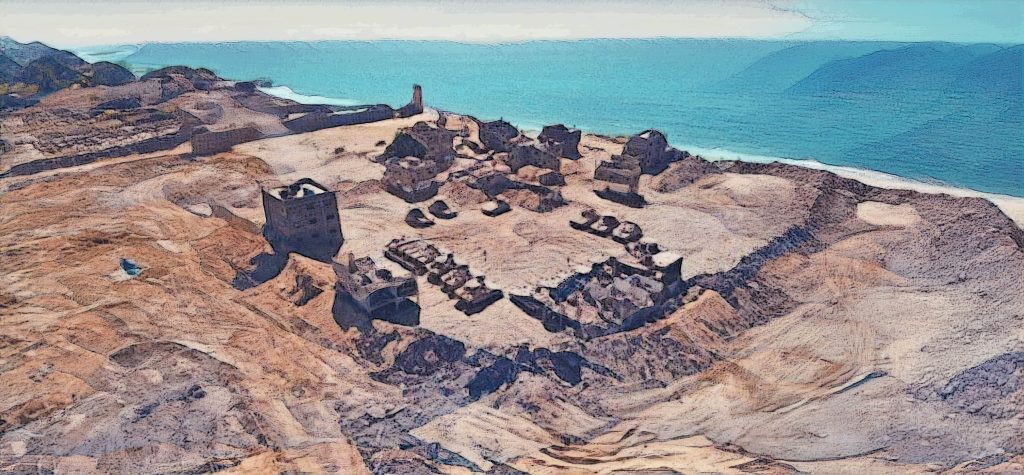

At the southernmost tip of Gaza’s coastline, where the sea meets the Egyptian border, lies a small village of a few dozen huts and homes. Though humble in appearance, this place, nestled by the waves, stands as a symbol of Gaza’s tragic history over the last decades.

The village’s roots trace back to the aftermath of the 1948 Nakba, when hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were displaced from their homes. It became a sanctuary for refugees, though it wasn’t formally established until 1965. Built as a gift from the Swedish people and Swiss soldiers of the United Nations Emergency Force, it was meant to provide for those uprooted. Today, a memorial in the village square marks its purpose. But over time, the settlement has been left to its own devices, a forgotten exile within a besieged land.

The 1,000-strong population of the Swedish Village has endured harsh humanitarian and economic conditions since its inception, but life has worsened significantly under the Israeli blockade of Gaza, in place since 2007. Fishing, once the village’s lifeblood, is prohibited along this coast by Israel. Israeli patrol boats relentlessly pursue local fishermen, arresting them and destroying their boats and nets, leaving many without a way to support their families.

The village’s isolation within the Rafah governorate compounds its hardship. With no access to public transportation, children are forced to walk up to seven kilometers on rough roads to reach their schools. Frequent and long-lasting power outages further exacerbate the challenges of daily life. The ever-encroaching sea has also become a source of fear, with coastal erosion forcing many to abandon their homes as waves draw closer each year.

Neglected for decades, the Swedish Village has come to be known as “the forgotten village.” The dilapidated homes and crumbling infrastructure seem to be of little concern to anyone. However, the Israeli forces have had an even darker vision for its future.

People clinging to what little they have

The Swedish Village is home to Tagreed Yousif Mekdad, who counts herself lucky to still call it home. She explains:

“I’m the daughter and sister of fishermen. Our lives depended on the sea. We’re far from the world, a marginal place – a border between continents. But we’ve always tried to get our voices heard, to reach the institutions that could help us develop the area.”

The village’s youth, eager for change, spent years trying to work, study, and improve their circumstances. But then came the latest exodus. Tens of thousands of people from northern Gaza have been forced to move south to areas like Al Mawasi in Rafah.

“Our lives were already difficult, but now they’ve become unbearable. High prices, people crammed together, lack of provisions… Every day, the Israeli occupation boats hunt our fishermen who are trying to make a living. Some are killed, others wounded. One day, a plane opened fire on the fishing boats, some of the fishermen returned home as martyrs, others were later sent home by the Egyptians.”

Tagreed recalls a night of terror:

“One time, we were making pastry bread to sell in order to survive this aggression. It was 3am when we heard a voice shout that a missile was coming. We ran as asbestos fell from the roof onto our pastries. Later, we searched the rubble for survivors with witnesses and a paramedic. They had targeted the house of Rabah Abu Salim, leaving five martyrs and nearly 20 wounded.”

And we said goodbye to our home

After being displaced with the other residents of Rafah, the residents of the Swedish Village began to tell themselves that the end was near. Israeli tanks were always roaming around. Tagreed and her family sought refuge in a makeshift tent camp in Brahma in the Sultan area. For ten days, they slept on the streets, struggling to find shelter and survive. Eventually, they returned home, though with grim resignation.

“We decided it was better to die in our own blood. We knew we would probably be killed and our house is more merciful than the tent. They could come for us any day, but at least we will be in our home.”

The threat of displacement loomed again when Israeli occupation forces desecrated a cemetery in Sultan. The villagers feared they would be scattered forever and lose track of one another. The families and neighbors had strong communal relationships. They all lived together hand in hand, so it was extremely difficult to bear the separation. They hugged each other and took each other’s addresses, and then left.

“That’s when we grabbed a few bags of our important belongings and started walking around like this, carrying our stuff.”

“As we walked to Khan Younis, my sixty-year-old mother muttered: ‘We shall see if we return or not…’ We walked and walked. I told my mom, ‘We should have taken more stuff with us. We’ve got nothing to sit on. Here’s the mat. It’s so thin and rough, she responded.”

A great fisherman, and an even greater human being

Maysra was a simple artist who loved art. Despite the village’s hardships, he pursued his passion for art, fitting in his studies between the long hours of fishing, a family trade passed down for generations. He was kind and easygoing.He worked closely with youth groups, always patient and meticulous, encouraging students to capture the finest pictures.

One morning, his younger brother and two neighbors pulled two loads of fish, but the first time they cast their net, they were targeted by a missile. Maysra’s brother Muhammad, along with another young man called Ahmed Shabana and his uncle Ibrahim al-Najjar were hit.

The forgotten village has been turned into a military outpost for the Israeli occupation soldiers who blew to pieces the small homes and the dreams for which the villagers sacrificed.

The inhabitants of the village, who knew each other so well and cooperated in all things in their everyday lives, are now scattered across Gaza with their hearts worn out from mourning.

And if the genocide is over… Where can they go back to?