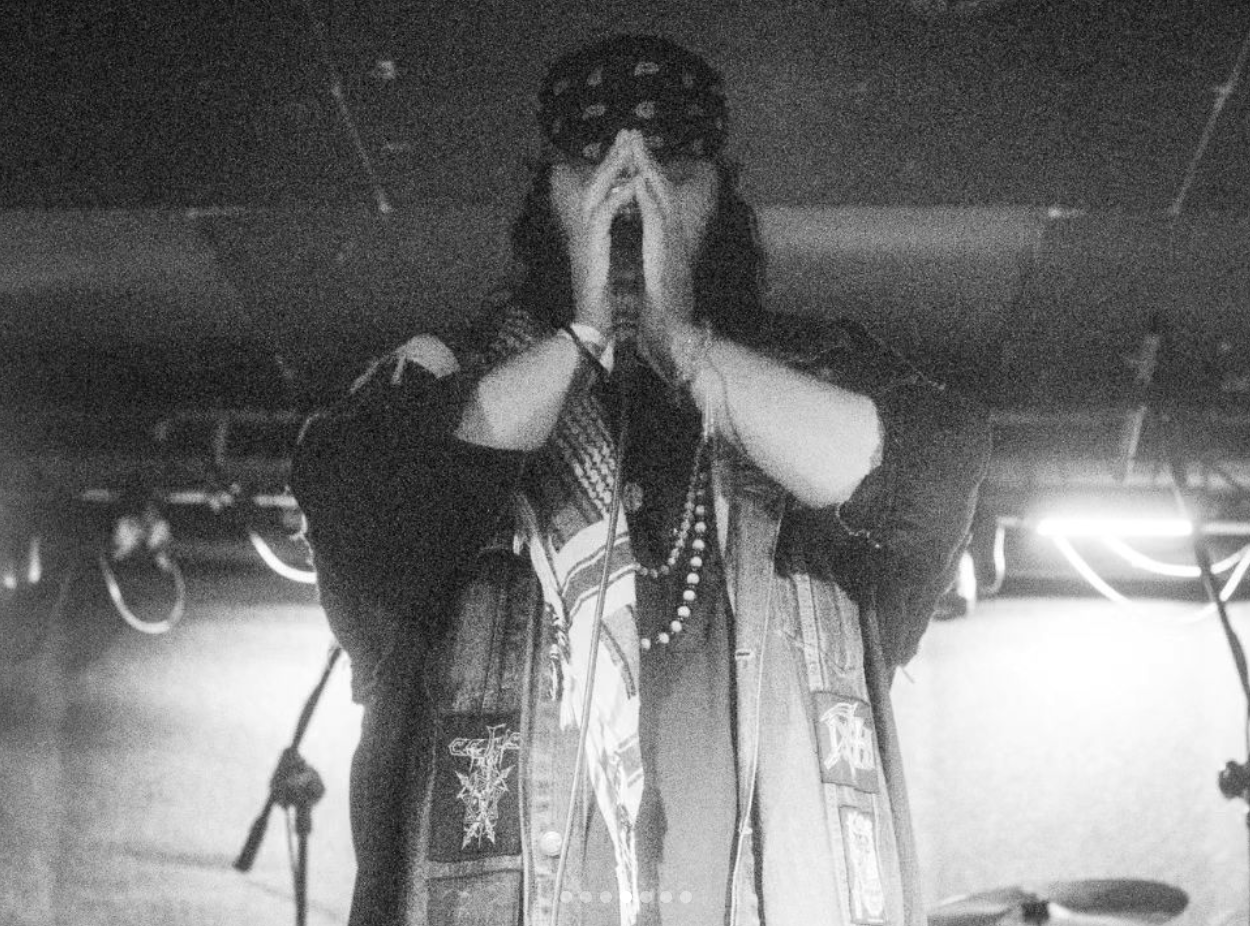

“Punk music was always meant to shock people,” says Hassan, famously known as Dozakhi (which means abominable and hellish in Urdu) among his peers and fans in the local punk scenes in both Pakistan and Germany. “I always believed in using that in a progressive way to advance good ideas,” he adds.

Dozakhi is the frontman of a Berlin-based hardcore punk band called Zanjeer. The group consists of immigrants from Pakistan, Britain, Australia and the former Soviet Union, and they recently performed together with other international hardcore bands in Berlin at Decolonoize Mini-Fest, a collective that organises shows “the old punk way: From The Scene – For The Scene.” They also played at a solidarity night for aid in Palestine in Berlin, joined by bands from Israel, Germany and UK/Egypt, paving the way for a new direction for the local punk scene for taking action to make a difference.

“Thankfully, in cities like Berlin, there is a sizable Ausländer (foreigner) presence, and you always feel at home, more or less,” says Dozakhi. “The best part of the show for me was that so many South Asian leftists from the Berlin activist community came to show their support,” he adds. “It’s really important that punk as a culture or lifestyle continues to be accessible and intersectional… places like Berlin are a lot more diverse when it comes to the punk scene, though, and generally, you find loads of Eastern European and South American punks across the country.”

A history of punk in Germany

Looking at the history of punk in Germany, one aspect that has remained true is the urge to create an impact through protest against the status quo and the boredom of convention. In the mid-70s, when punk music gained popularity in the UK and the US, it trickled into Germany as well. What made this history interesting is how differently punk music’s impact partitioned Germans on either side of the wall.

Historically, German punk was about shocking people out of political complacency and state oppression. This feeling still holds true for punks now, especially those from migrant backgrounds who are trying to hold space and have their message heard in an otherwise non-accessible scene.

“It is a white-majority country, so of course it’s going to be like that,” says Dozakhi. “But you do have to pause and think when you see that other spaces, such as hip-hop and electronic music, have way more POCs in them compared to punk. And let’s not forget that Turks and Arabs have been here as guest workers for decades, and their children were born in Germany and had to develop their own subcultures because German society just wouldn’t accept them.”

Punk music in migrant languages

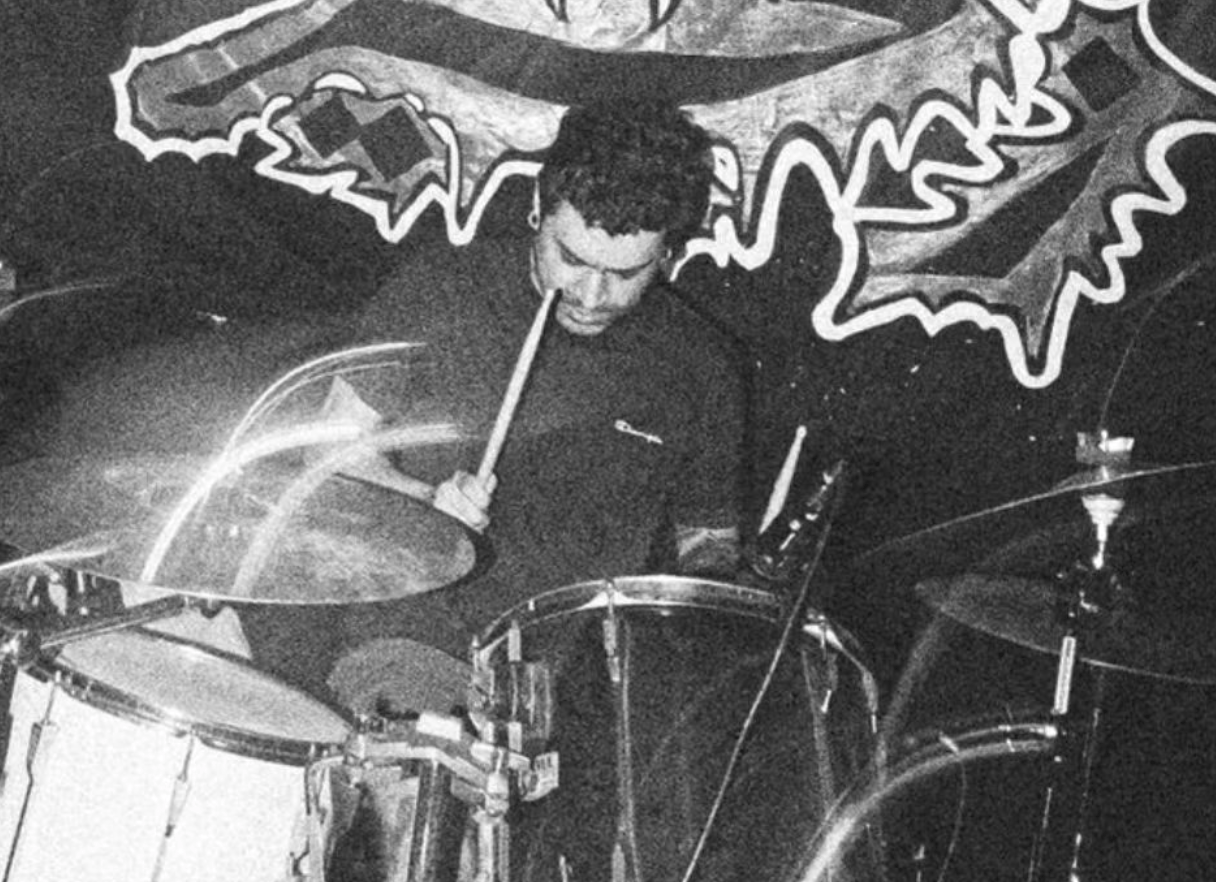

Zanjeer’s drummer, Steve, and Dozakhi both moved to Germany to pursue higher education and have been here for three and five years, respectively. Both have played in punk bands in their home countries, but upon starting Zanjeer, they decided to write music in languages attached to their identities. This helped set them apart from European bands and encouraged others in the scene from migrant backgrounds to do the same.

On their first EP titled Parcham Buland Ast (which means “The flag is high” in Farsi), there are songs in Punjabi, Urdu, and Farsi, creating an unexpected but harmonious mix. In fact, the band name ‘Zanjeer’ means ‘chain’ in Urdu, Hindi, and Farsi.

While Farsi is not Steve’s native language, it played a role in his life while connecting with family in Iran. Despite English being his ‘native’ language, Steve felt dissatisfaction with the lyrics he wrote in English. “I thought that as most listeners wouldn’t understand them straight away, it provided a veil of mystery that I found comforting,” shares Steve. “The response from fans has been great. People think it’s cool and necessary that punk bands are not just singing in Western languages. I’ve seen people get emotional hearing a language they have a connection to in a style of music they like, where they had never heard it before.”

According to Dozakhi, the impact of releasing two songs in Farsi has been larger than expected. The Iranian diaspora includes many dissidents. When some express to the band that they feel they have a voice in the punk scene, it is extremely significant for Zanjeer. “Honestly, I have so many Iranians—diaspora as well as locals—coming into our inbox, both punks and non-punks alike,” says Dozakhi. Through Zanjeer, the band members have come in contact with the emerging punk underground scene in Iran, such as the band TØF, who are in the process of releasing an EP soon.

Immigrant punks in Germany

As immigrants, there is still much to unpack when navigating the German punk scene, especially in the wake of the ongoing Israeli war on Palestine and Germany’s role in it, and how that trickles down into the country’s punk scene and its connections to the Antideutsche movement.

Things have been politically charged across Germany, especially with the recent local elections and the rise of the right-wing AfD, gaining popularity even among Gen Z voters. However, the punk scene has historically had a connection with the left, making the presence of the Antideutsche movement difficult for immigrants in the scene to understand.

“The automatic connection between punk and the political left has been an ongoing debate since punk has existed,” says Steve. “Some people take an internationalist solidarity stance, while for others, it’s more about personal autonomy and freedom of expression—not that these are mutually exclusive camps, of course.”

Because of the connection between punk and the political left, at some point, the Antideutsche movement became intertwined with parts of the German punk scene. However, over the past year, it has become increasingly clear that Antideutsche continues to be a harmful movement with less relevance over the years in left-wing politics.

Confronting the Antideutsche

Both Steve and Dozakhi have had run-ins with people in the music scene who share Antideutsche ideology. “I found it incredibly strange, almost offensive. The existence of this sect came as a big surprise to a lot of the international punk community post-October 7, 2023,” shares Steve. “But personally, I had been waiting for something like this to happen so that all these pro-military, pro-colonialist, pro-genocide ‘punks’ could start coming out of the woodwork.”

For Steve and Dozakhi, it is particularly insidious that this movement uses the historical context of Nazi genocide to display their sentiments against German heritage while being entitled to use it to preach what they believe is morally correct and justified.

“They aren’t consulting Jewish leftists or Israeli punks, or indeed anyone in the Middle East, when coming up with these arguments—just their own white German pseudo-intellectual circles,” says Steve. “We have connections with punk bands in Israel, and they can’t stand these Germans who feel entitled to speak on their behalf because of what their grandparents did or whatever. It’s totally messed up and sick.”

View this post on Instagram

Dozakhi adds: “I have even seen them cancel Israeli punk bands like Holocausts, labelling them anti-Semitic. As far as I know, they [Antideutsche] were not really the norm among German punks once, and I believe it will change eventually. There is already resistance to their ideas. Even Israeli punks, including some of my dear friends, really find them ridiculous.”

A punk community

Being an immigrant in a punk band in Germany, singing on stage while sporting a (banned) keffiyeh, and navigating the political stance of a country you want to turn into a home is excruciating in the current atmosphere if you want to have a voice. But for Zanjeer, the support for their music, not just in Germany but from international diasporas of Iranians, Pakistanis, and other European punks, has been a tremendous encouragement.

Dozakhi has been told by people from Los Angeles to New York that they feel inspired to make punk music in Farsi, as well as Urdu and Punjabi speakers who listen to Zanjeer. For Dozakhi, the mission of the band feels like a success, and he hopes that in his lifetime, he will be able to listen to punk in countless South Asian and West Asian languages.

“Honestly, I have only ever been humbled by the response of people whenever we play. They’re so happy to see people singing in different languages and coming from different places,” says Dozakhi. “I think that’s fucking beautiful and a testament to the internationalism of punk!”