Women have played an instrumental role in the media, showcasing remarkable courage and resilience. Their presence and voices have shaped narratives, challenged norms, and broken barriers. From journalism to filmmaking, women have fearlessly pursued stories that highlight societal issues and champion equality. Their unwavering determination and bravery continue to redefine the media landscape, thus paving the way for future generations.

This has precisely been the Mediterranean feminist network MedFemiNiswiya’s endeavor, which UntoldMag acknowledges through a conversation with Cristiana Scoppa, an Italian Journalist and program officer, and Mahacine Mokdad, a Moroccan journalist, producer, and independent filmmaker.

What is the purpose of creating MedFemiNiswiya and what is this network?

Cristiana Scoppa: MedFemiNiswiya is a network of feminist journalists from countries around the Mediterranean Sea. It is officially registered as a non-profit association in France under the name of MedFemiNiswiya.

This network was born out of a project started by a French foundation, called The Mediterranean Women’s Fund, which is a women’s foundation that supports the feminist movements around the Mediterranean.

In 2018 the advisory council -a group of women from various feminist associations from around the Mediterranean that regularly meet at the Mediterranean Women’s Fund- discussed the issues and priorities for the foundation to support women’s organizations around the Mediterranean. One critical issue that they highlighted was the lack of information about feminist organizations, about the challenges that women are facing. They realized that very often they were struggling with the same issues, maybe in Croatia or Morocco, but there was nothing in the media about these common challenges.

So, the first idea for this organization was to nominate feminist journalists, whom they were already working with in their respective countries and then the Mediterranean Women fund conveyed a first meeting of journalists. Mahacine was among them.

Mahacine Mokdad: They invited these journalists and heads of female organizations who were already either friends or acquaintances, so it immediately felt like a family.

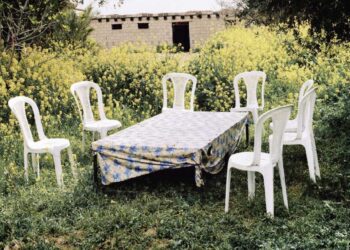

We first met in Caranzano, Province of Alessandria, Italy, in a beautiful house called AltraDimora, owned by a kind woman. For years, AltraDimora had hosted many such events and meetings and had been a gathering place for women thinking of solutions for their common issues.

This time, it was our turn to be hosted there. We spent three entire days together, sharing the everyday in this common space. At first, as we were brainstorming, we began by identifying the challenges faced in our respective countries. The brainstorming continued on the following day and we tried to articulate exactly what it is we needed- another NGO? Funding? A new NGO that would focus on women’s rights through information, articles and videos, etc…?

The third day we came up with the idea of a platform: we all agreed that this would become our mission, we formed our editorial board and confirmed the topics we wanted to tackle. And that was the beginning of this journey.

Mahacine, what motivated you to pursue journalism and advocacy for feminism, representing and to focus on Mediterranean perspectives?

M: During the years I worked for the second Moroccan channel, I specialized in reporting on rural areas, within forgotten communities that are often considered “useless”.

It was crucial for me to meet the women and men of these communities and give them a platform to publicize their struggles as well as the means used to confront them. Nothing was more encouraging for me than seeing the story of a young girl from the Atlas Mountains inspiring other girls in other regions and helping them believe in their abilities to break out of the social trap that prevents them from pursuing their studies and even more.

In Morocco, television is a powerful medium among rural communities. They follow very closely what is happening in the world through the small screen and the stories of their sisters, which often resonate with their lives and thus have an immeasurable impact on them. Despite everything that can be said about television as an instrument of propaganda, it remains a traditional medium that we must continue to invest in so that information continues circulating among communities forgotten by decision-making centers.

And Cristiana, what motivated you to pursue journalism advocacy for feminism, representing Mediterranean perspectives?

C: I became aware of the privileges connected to being a man as an adolescent girl when my parents encouraged and justified the freedoms enjoyed by my brother as opposed to me and my sister with the words “Perché lui è maschio” … “Because he is a boy”.

I understood that this was not only the attitude of my mother and father, but the behavior of society in general, as women and girls were requested to protect themselves against possible assaults from boys and men by restraining from doing what they would have loved to do, obeying and being modest. On the opposite, men and boys continued to enjoy total freedom, although they often abused it and assaulted, raped, and killed women and girls.

I found all these totally unjust and completely unacceptable. Feminist journalism became my way to promote social and cultural change, women’s rights, and freedoms.

Cristiana, can you tell me how many members have joined the network since 2018, and how you serve journalism in the many different countries you cover?

C: We are present in all Mediterranean countries except Albania and Slovenia where we have no representatives and no journalists on the ground who can contribute to our network.We have an established salary/fee per article which is the same all over the Mediterranean. This means that for some countries the work they do is well compensated, while for others the wage is low according to the market. This sisterhood agreement regulates the network and makes it possible to value the work we do on an equal basis- even though we are aware that the costs for living are not equal.

In practical terms, our work revolves around organizing editorial meetings and online Zoom meetings. We involve the members of the network and work in teams. We have an administrative team working on funding and so on and we also have an editorial team that works on the production of a MedFemiNiswiya content and ensures the articles are translated.

What is the purpose of your publications in three languages (English, Arabic, and French) despite having members from all over the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Africa?

C: As English is an international language used and understood everywhere by a majority of people, publishing our content in this language is very important. In Arab countries, there is a lack of feminist content and therefore a crucial need to produce content in a language that can be understandable by people who might not have access to education in other languages. As for the French language, I must add that we were funded by a French organization and MedFemiNiswiya was established in France.

All the writings have been translated into these three languages by journalists and experienced people in our team.

We have just created a section on the website called VO (original versions), which hosts articles in the original language they were received in. This is important since it allows local publics and readerships to have access to locally produced content. By way of example, my colleagues and I in Italy provide articles in Italian, thus ensuring their dissemination within our country.

Mahacine, from your point of view, what progress has been made in terms of women’s representation in leadership roles within Mediterranean cultures and what steps can be taken to further improve this?

M: All over the Mediterranean, as in the rest of the world, the fact that women deserve to occupy leadership roles is nowadays acknowledged. This does not unfortunately mean that women have achieved a fair representation in these roles, be it in the political, economic, or cultural domain. Moreover, in many countries, we observe patriarchal political forces that emerge and affirm themselves, with significant backlashes for women’s rights and freedoms they had conquered so far. It is therefore important to continue to provide information on these issues, to inspire and promote the active participation of women when it comes to fighting for their rights.

Cristiana, as a journalist focusing on women’s issues, how do you approach cultural sensitivity while highlighting instances of discrimination or inequality faced by women in the Mediterranean, Middle East, and North Africa?

C: The Mediterranean has always been a space of cultural exchange. But increasingly, nationalist political movements are on the rise in the various countries around its shores. Nationalism goes hand in hand with sexism and racism: it is, therefore, important to recognize diversity as a constitutional feature of humanity and to promote citizenship as a universal concept, one that applies beyond borders, and that can be understood as the entitlement to economic and social well being, equity, respect and freedom of choice, regardless of the nationality, place of birth, sex, and gender.

By portraying stories of women in my journalistic work and highlighting their achievements and successes, I try to keep these principles in mind and show that improving the condition of women and respecting human diversity is beneficial to everyone, not only to women and girls.

Mahacine, can you give us an example of a journalistic piece from Morocco or any other country that was particularly important for you and/or for the MedFemiNiswiya network?

M: Several issues tackled by the MedFemiNiswiya teams stood out this year. Whether it is menstrual precariousness, the precarious situation of women in prison or the situation of rural women, the different dossiers which encompass a number of articles from several Mediterranean countries have not only made it possible to shed light on women’s struggles to obtain primary rights but have also showed that Tunisians, Spanish, Italians… are the guarantors of food security in their respective countries but yet suffer from similar problems and thrive to obtain the same rights. For example, the stories of shepherdesses in Italy echo the situation of clam pickers in Tunisia who suffer from exploitation, the absence of favorable working conditions, while also being subjected to intimidation from their male colleagues when they dare standing in the way of any form of discrimination.

Cristiana, could you share some pivotal moments or experiences that shaped your journey as a journalist/feminist from the Mediterranean region?

C: In 1997, as a journalist working with the feminist magazine “Noidonne” (WeWomen), I was invited by the feminist NGO AIDOS -the Italian association for women in development- to travel with its founder and president Daniela Colombo to Gaza. The many women I met and interviewed, the spirit of renaissance and the energy of women who started small enterprises with the support of the business incubator created by AIDOS, and their political engagement considering the coming political elections in the Strip continue to hunt my memories as I watch the destruction and suffering of Palestinian women, children and men in these terrible times.

And you Mahacine, can you tell a story of collaboration among different Mediterranean countries?

M: Collaborative projects between MedFemiNiswiya journalists are the strength of the network. The editorial team and the management committee of the network decided a few years after the creation of the network that it would be crucial to invite journalists from around the Mediterranean to express themselves on the same issues and to share various opinions and possible solutions. For example, the Women and Prison dossier brought together articles about Lebanese, Palestinian, Turkish, and Italian women. Their stories are strong and very precarious. They shared the experience of prison as a place of physical and mental abuse for women in which their basic rights were consistently violated. The predominant law of Omertà made it difficult to carry out real investigative work . What emerges from these articles are the forms of resistance and creativity that command respect: in the period of her incarceration, activist Zehra Dogan, for example, managed to create numerous paintings based on organic products and to then smuggle them outside the prison where they ended in exhibition halls in NY, London and Basel.

What is your message as a network to women around the world?

C: Although the challenges faced by women are still considerable and the seemingly little progress achieved can seem discouraging, we must recognize that the large majority of women today, all over the globe, are aware of their right to empowerment and are determined to resist against the imposition of limitations to the freedoms they enjoy- especially when we compare it to the situation of previous generations. This is a very encouraging sign, one that I hope MedFemiNiswiya will be able to document and offer as an inspiration to many more women around the world.

Mahacine, how do you personally and professionally think a Mediterranean feminist network can resonate or have any impact for the more Global South feminisms around the world, such as Africa, Latin America, or countries like Iran or Afghanistan?

M: The countries of the South are culturally rich and have several points in common despite their historical and political differences. Notably, women encounter the same difficulties: the right to abortion, parental affiliation, the marriage of minors, schooling of young girls, and so on. The experience of a Moroccan woman living in the Rif mountains necessarily echoes the experience of her peers in Brazil, Panama or Guatemala. Religious contexts and patriarchal societies indeed condition the state of advancement of human rights in general and those of women in particular, but one thing is certain: a challenge taken up by Mediterranean women can only inspire and encourage reflection on the same subject on the other side of the Atlantic or in Asia Minor. Dr. Martin Luther King once said: “No one is free until everyone is free” and it is a maxim that continues to resonate today.