UntoldMag proposes ECCHR’s founder Wolfgang Kaleck interview with Italian artist and photographer Laura Fiorio and Ethiopian-American author Maaza Mengiste about Fiorio’s project “My Fascist grandpa” on archives, the forgotten colonial period in Ethiopia, women in war, photography, and much more, originally published in ECCHR’s 2022 Annual report.

Questioning her grandfather’s fascist photo archive, Laura Fiorio, in her project My Fascist Grandpa, focuses on Italy’s fascist and colonial history through the lens of shared family histories. Her grandfather was an avowed fascist who participated in the colonial mission, scarcely remembered today, in what is now Ethiopia.

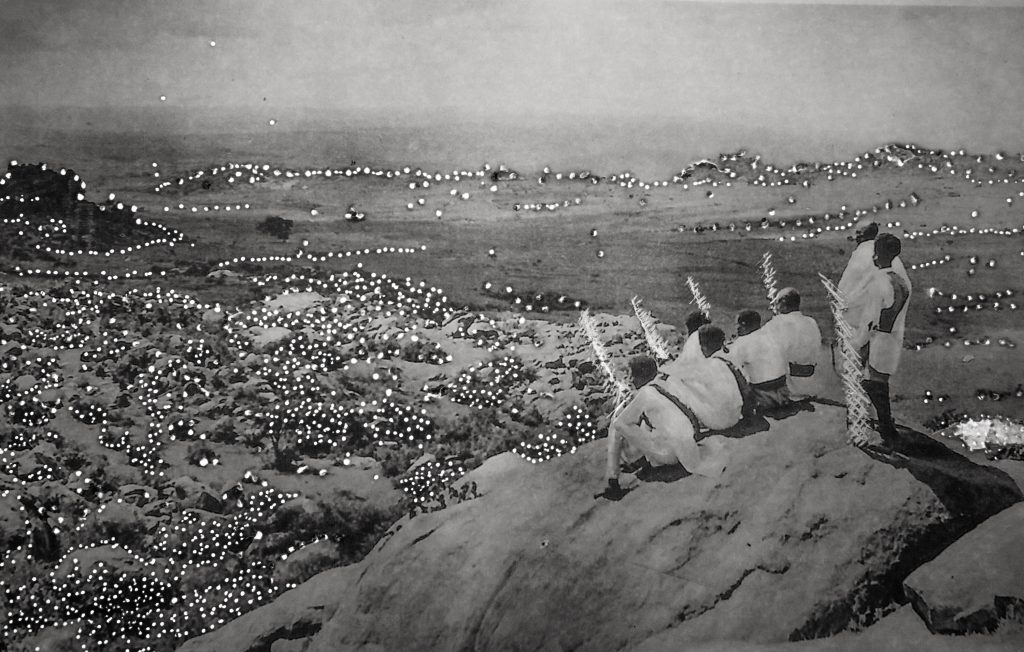

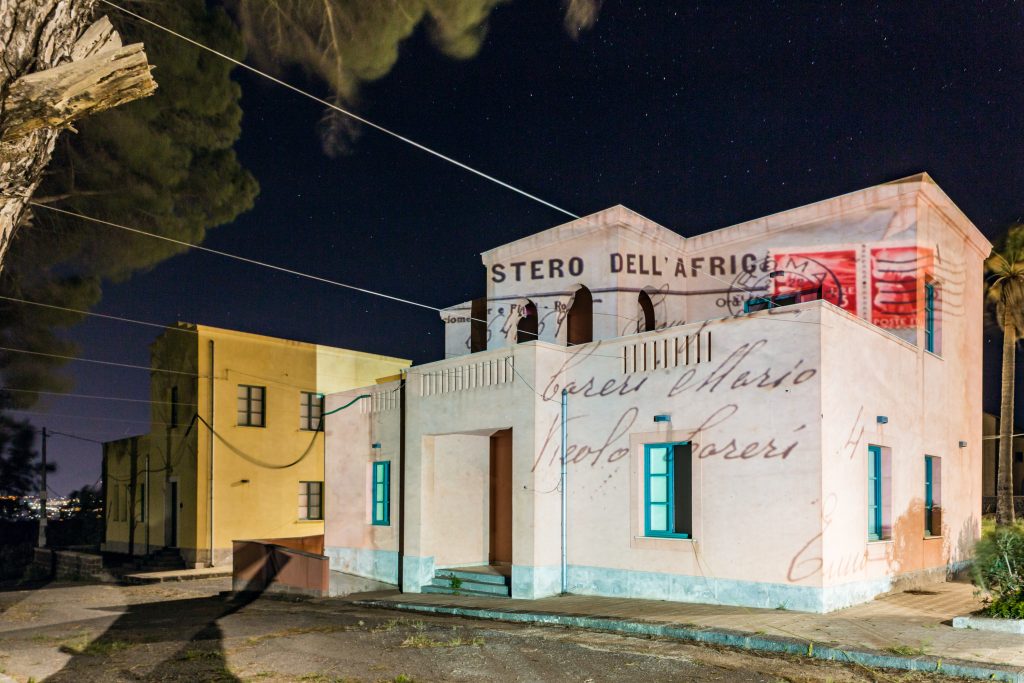

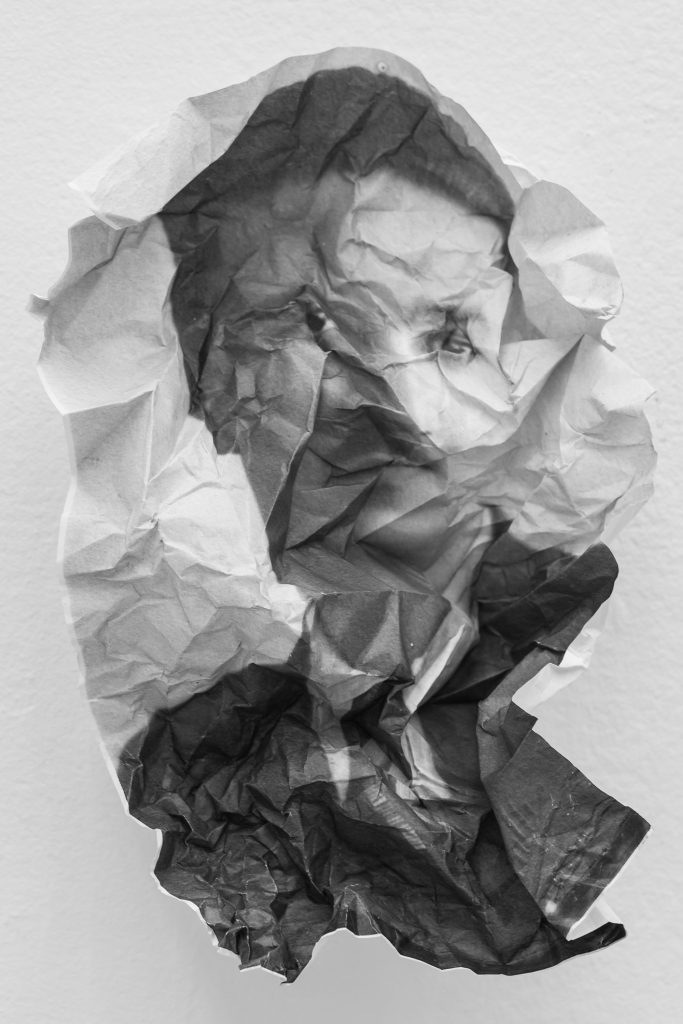

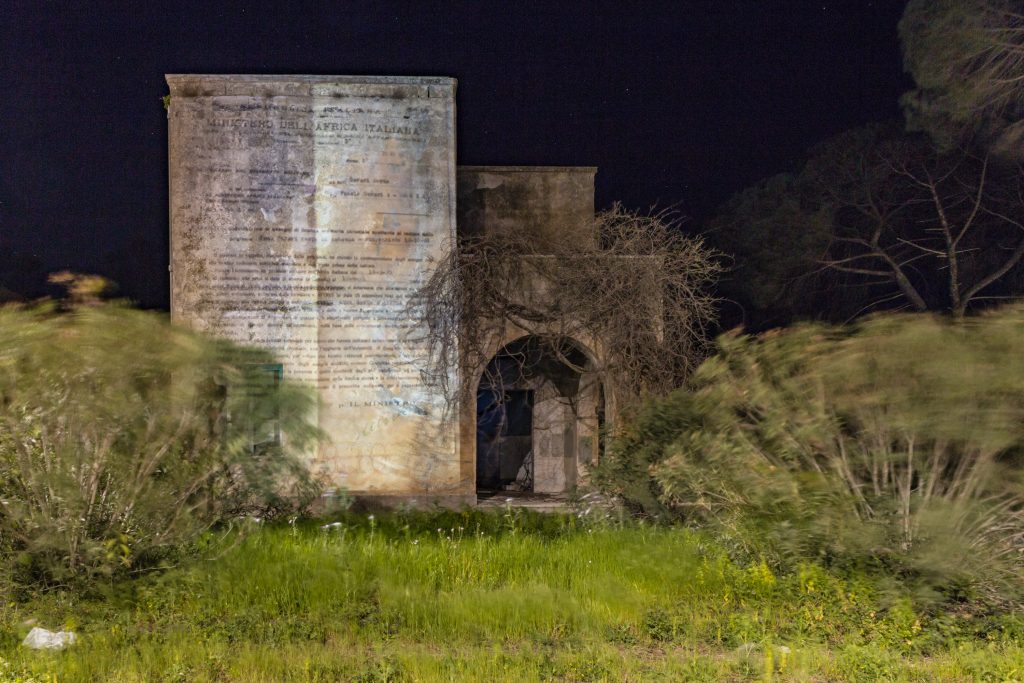

Based on photos from private archives, the project My Fascist Grandpa aims to transfer individual stories and memories – often forgotten or taboo – out of the private realm and into the public space in order to provoke critical reflection. To this end, Fiorio used conventional archival techniques to symbolically gather photography, mementos and letters into archival crates and then projected them onto the facades of fascist architecture in a collage-like intervention that defamiliarizes these objects and uncovers the difficult heritage hidden behind modernist architecture.

Through her work, she was introduced to Maaza Mengiste, who also conducted archival work in Italy. Mengiste visited numerous colonial archives, found memorabilia at flea markets and increasingly came across accounts of women in the Ethiopian army who resisted the colonial land grab by Italian occupying forces – a phenomenon almost entirely absent within memorial culture. She also discovered evidence of this in her own family, as her great grandmother fought in the Ethiopian army. Mengiste’s novel The Shadow King, highly praised internationally, revolves precisely around this narrative.

WK: Let’s talk about Italy’s fascist history, and a chapter of it which is fairly unknown even to an Italian audience, let alone a European one – the colonial war in Ethiopia. Laura, can you give us some insight into your work “My Fascist Grandpa,” which is part of ECCHR’s Annual report 2022?

LF: The research started with a site in Sicily, built in the fascist period by the Entity of Colonization of the Sicilian Latifundium, as that territory was considered backwards and in need of modernization. It’s important to recognize that the colonial past linked to these heritage sites is not critically discussed, not only in Italian territory, but also abroad. There is a collective amnesia about the occupation of “Italian Africa” – as it was called – while the role of Italy in colonial history is always minimized, if not denied.

Some years ago, I found pictures from my grandfather who was in the fascist army during the occupation of Ethiopia. You can see him with his comrades, in tourist-like pictures, smiling in groups or with local people in an innocent way while they were indeed colonizing the territory. What I decided to do was to make these pictures public, projecting them onto those architectures. Local people involved in the project also brought in some of their own material, and we did some workshops around these images, discussing what is to be done with this difficult visual, as well as monumental, heritage. Painting, cutting or other kinds of collective interventions were symbolic actions that we engaged, in order to add a layer to this shared debate and to draw out these invisibilized narratives.

WK: Maaza, you were born in Ethiopia in 1971, just a few years before the overthrow of the emperor Haile Selassie, who had ruled Ethiopia for more than 40 years, including the colonial period. And what happened then was actually not particularly a liberation, but a so-called Marxist-backed revolution in 1974 that brought a wave of repression with a very brutal regime, which also forced your family to leave the country. At some point, you started researching your own history.

MM: In one way, I’ve always known about the history of Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia and the war, and then the eventual victory over the fascist army. When I was thinking about writing a book, I thought this was a story that I wanted to tell because it felt like such a simple story of good versus evil. At the time, I wasn’t writing. I had never written a book. So, I think The Shadow King was many years in development even before I started writing it. And then, when I started really doing this research, I lived in Rome, and I was looking through fascist archives. I had already written my first book by that time, and I thought I knew the story that I wanted to tell. But the more I researched this history, the more complicated it became.

Laura spoke about photographs, and when I lived in Rome, I started thinking about the ways that family photographs could offer another kind of history that the archives were not telling me, partly because these photographs, taken by soldiers on the ground with their own personal cameras, did not have to go through censorship the same way that newspaper accounts or actual official documents were censored by the fascists. So, I started trying to find all of these personal photographs, and this completely changed my understanding of this war.

WK: In a way, it seems like it was an unwritten history. Why was there not more artistic or historical work, for example, from the Ethiopian side. The Italian side did what all the other colonial powers in Europe did: they tried to blank out this part of the history. How do you explain that?

MM: I think that Ethiopians after this war were documenting the war in their own way. There were no cameras. Ethiopians didn’t have cameras when they were fighting in the hills the way the Italians did. But after the war in Addis Ababa and across Ethiopia, there were photo studios that were set up by Greeks, by Armenians, by Ethiopians, by Eritreans. They were using the skills that they had often observed with the Italians or within other communities. They were starting to get access to cameras and also to what they could not photograph during the war. They started recreating and reenacting scenes in photo studios. They would take their old uniforms or their horse, if they had a horse, and they would stand in front of the camera in these studios, and that would represent their time in the war. There were songs that were created that would commemorate certain battles and certain fighters. There were books that were written and some autobiographies about their time, people’s time in war. I think your question to me is why? Why were some of these things never talked about? A lot of it has to do, I think, with Haile Selassie, who came back from the war.

WK: In 1941.

MM: 1941, and he told everyone: “We are going to forget and forgive what happened. Your Italian brothers,” there were many of them that chose to stay in Ethiopia rather than go back to Italy, “They will become part of our family. They will be in our community. The one who did something wrong was Mussolini.” So, there was no reckoning with what happened, no reckoning with war crimes. And if you have 40 years of this and then a revolution comes in 1974 and people have never had an opportunity to talk about the trauma of 1935 to 1941, to talk about what actually happened and what people were capable of.

WK: You write about a part of the story you described in your own words as “no one ever talked about the women.” And so, you focus very much on the role of the women in that war.

MM: In my research through photographs, however, I started discovering photographs of women in military uniforms in the Ethiopian army with their rifles. I started reading small accounts in soldiers’ diaries of women in the field when they were fighting. And I started thinking: no one ever told me this. There is an entire history here. Of course, they would have been in the war if they could. I know that if they were close enough to follow an army and collect the dead, they were close enough to be hit by bullets. Why wouldn’t they arm themselves in turn? And that really changed the direction of my novel. And then, the real detective work began by trying to piece together testimonials if I could find them, family memories from people that I knew, but also this archival research where the stories were not always apparent. But if I looked deep enough, I recognized that some of these women that I saw in the images were definitely soldiers.

WK: It was interesting to read in one of your interviews about when you saw a woman in uniform for the first time in a photograph.

MM: That photograph showed me a history that I had not really been aware of before. It was a woman in uniform with her horse. And I looked at that image. What it told me was, if there was one woman, then there were likely five. And if there were five, there were maybe ten. And if there were ten, there were maybe 50. And I went back through old documents that I had been reading, newspaper articles, and because I saw that photograph, I suddenly realized that I had missed a couple of articles that spoke about women in the Ethiopian army, leading men, leading charges.

What I realized is that from researching other wars, other liberation movements, reading the testimonies of women in antifascist movements from Spain to Italy around the world, realizing that they fought, and when they came back to camp, they had another battle that they had to fight. And it was often with the men in their own camps. Ethiopia is no different. We’ve known the place of sexual violence in war. It seems to go hand in hand. Whereas war is about being masculine, it is about being aggressive. It’s about surviving. Where does a woman fit into this world? If war makes a man out of you, what does it say about you if a woman is fighting next to you or against you and actually might be doing better? And these were the questions that started to really develop. I think this influenced the direction of The Shadow King, because these women soldiers were having to defend territory, land, but when they went back to camp, they had to defend their bodies as territory. But they were also fighting the Italians who saw them as territory to be conquered.

WK: Who is supposed to write this forgotten chapter of history, and to whom is your work directed?

MM: Oh, that is a good question. I think the question is who’s in my head – what image – who do I envision? When I was writing The Shadow King, I really envisioned someone quite like me who lived most of their life outside of Ethiopia. I was writing for someone who doesn’t know this history. And for those who are curious about the many, many ways that authoritarian dictatorships can happen. With bullets, but also with photography, for example. I think I was writing for the curious.

LF: This work is processual and collective, I think it’s for everybody who wants to participate. A lot of silenced histories are collective ones, and it’s worth creating a safe space for them to be told. The project’s focus is the past, but of course it’s to sensitize us to the present, looking also at the current political situation in Italy – the government we have is extremely linked to the fascist ideology. I mean, we can just look at the news a couple of days ago. They literally left 79 people to die not far from the Italian coast. The question is why this is still happening, why these power structures are repeating themselves. I think because the people aren’t able to have a space for counter-narrative to the propaganda. And it’s because of the structural violence we live in, every day – we don’t have time to gather together and care for each other, to share traumas and to look for solutions. Colonialism is not something in the past. It is still in the present, and it’s in the fabric of society. And it belongs to the present extraction and the present violence and what is happening now. It’s not called colonialism because we are told we are living in postcolonial times, but it’s still there in another way, with another name, maybe capitalism, globalization, extractivism or whatever. But that’s just changing the names. The violence and the structures remain the same.

“In 1940 the Italian fascist regime established the Ente di Colonizzazione del Latifondo Siciliano (Entity of Colonisation of the Sicilian Latifundo), following the model of the Ente di Colonizzazione for Libya, and the colonial architectures in Eritrea and Ethiopia. Territories that for the regime were to be ” drained,” “modernized,” and “repopulated,” as they were considered “empty,” “underdeveloped,” and “backward.”

To this end, the Ente di Colonizzazione del Latifondo Siciliano inaugurated eight boroughs and as many remained unfinished. Today most of these villages have fallen into ruin.

What does not seem to be in decay in Italy, however, is the persistence of colonial and fascist rhetoric, culture and policies. Despite the fall of fascism following World War II, the de-fascistization of Italy remains a woefully unfinished process. This is one of the reasons why even today Italy has maintained visible architecture, monuments, plaques and a toponymy celebrating the fascist regime.

Moreover, Italy – having lost its colonial possessions during World War II – has never undertaken a real process of decolonization.” (Text extract from “Towards an Entity of Decolonisation” by Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti (DAAR).

The project “My Fascist Grandpa” is part of a larger collective work and collaboration with Mario Margani, Entity of Decolonisation, DAAS and DAAR and Garage Arts Platform.

The Podcast was produced from ECCHR, in collaboration with Maaza Mengiste.