Since 7 October 2023, the Palestinian community in Germany, especially in Berlin, has been subjected to intense suppression of their protests, cultural symbols, voices and narratives. This crackdown has significantly hindered their ability to publicly express grief and outrage against the State of Israel’s bombardment of Gaza, which according to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) constitute a “plausible case of genocide”.

By banning protests, the German state not only negates Palestinians their right to free expression and peaceful assembly, but also seeks to control the public narrative and visibility of Palestine and Palestinian life in Germany. Although the intensity of this suppression escalated on 7 October, it is part of a historical politics of erasure, diminishing and eradicating the collective existence and identity of Palestinians in Germany, through repression, censorship and discrimination.

Silencing of Palestinian voices after 7 October

The Berlin State’s and police’s response to Palestinian solidarity protests since 7 October, especially in the first weeks, has been notably severe. They have either outright banned gatherings or resorted to aggressive measures to control them. From 11 to 20 October alone, the European Legal Support Centre (ELSC) counted 600 detentions in Berlin, including of minors among those showing solidarity with Palestine, alongside a series of criminal and administrative proceedings. According to the organisation Campaign for Victims of Racist Police Violence (KOP) the extent of police brutality has been captured in various videos showing the use of pepper spray, deployment of police dogs, and physical aggression, which resulted in numerous injuries.

Just to give an example, on Indigenous People’s Day, 12 October 2023, a diverse coalition of anti-colonial groups, including indigenous, Black, queer, and feminist collectives, staged an anticolonial protest in front of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Berlin. The demonstration was disrupted when police forcefully intervened, specifically targeting those carrying Palestinian flags, because, according to them, “Palestine has nothing to do with colonialism”. The organisers of the protest refused to exclude those standing in solidarity with Palestine from their anticolonial protest, and the police responded. This led to the violent arrest of approximately a dozen individuals solely for possessing flags and banners that were linked to Palestine.

The racial profiling, interrogation and unlawful arrests of people wearing the keffiyeh in Neukölln, a district home to a considerable Palestinian community, is yet another manifestation of anti-Palestinian, anti-Arab, and anti-Muslim racism that guides this repression. It is not a coincidence that the massive police presence and violence targeted the district of Neukölln, where the criminalization of migrant places and stigmatisation of people of Arab, Turkish or Kurdish origins is a common practice.

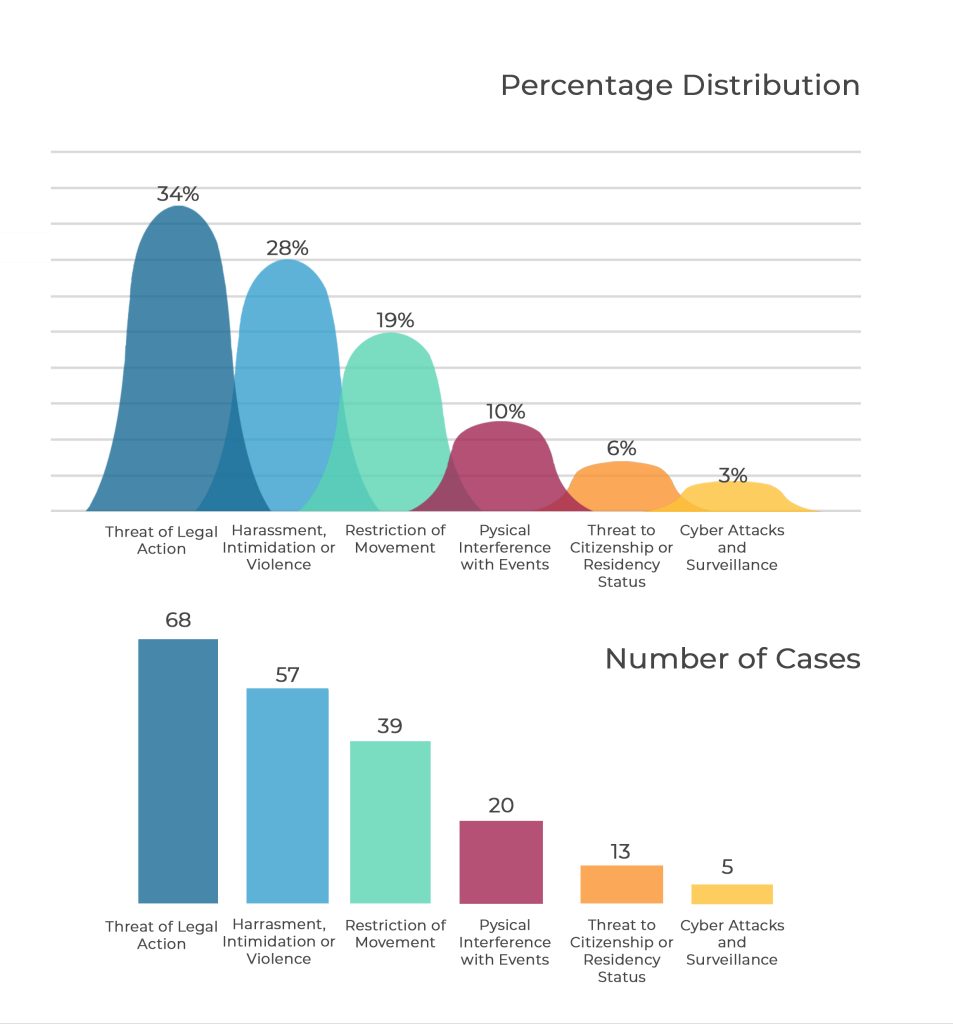

Between 7 October 2023 and 31 January 2024, the ELSC documented 202 cases of political repression, including 68 threats of legal action, such as administrative civil rights complaints, as well as 57 cases of harassment, intimidation, or violence against individuals or groups advocating for Palestinian rights. Additionally, 39 instances where individuals or groups faced restrictions on their freedom of movement, through denied access to or use of specific locations were reported. In 20 cases, physical interference by individuals or groups disrupted Palestine related events.

Anti-Palestinian repression not only plays out in the streets and public spaces of the country, it penetrates a wide range of the political spectrum, official institutions, civil society, cultural institutions and media.

In a particularly controversial move, the Berlin Senate Administration, in mid-October, issued a letter to schools in the city. The directive allows schools to prohibit the display of Palestinian symbols, including the keffiyeh and “Free Palestine” badges. The keffiyeh, a traditional Palestinian scarf, holds immense cultural significance and is viewed as a historical symbol of resistance against the colonisation of Palestinian lands and people.

Furthermore, on 21 December 2023, the Berlin Senate Cultural Administration decided that the awarding of funding would be subject to the condition that applicants sign an ‘antisemitism clause’. The clause uses the controversial and legally problematic working definition of antisemitism of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance and its extension by the German government, which enables labeling any critique of Israeli government policy as antisemitism, and hence, a ground for exclusion. In response to mounting pressure from artists and cultural workers, the Senate dropped the clause after one month of its introduction.

Cultural, academic and educational institutions face mounting pressure to silence Palestinian voices or those in solidarity with them. The cancellation of the award ceremony of Adania Shibli’s book “Minor Detail”, which won Germany’s 2023 Literaturpreis, reflects a broader attempt to stifle Palestinian voices within cultural and intellectual spheres. Various unfounded allegations of antisemitism, hidden antisemitism, or the argument that the topic of Palestine is deemed “too sensitive”, “too complex” or “inappropriate at this time” have been employed to hinder the presence and expression of Palestinian solidarity, voices and narratives in the cultural sphere.

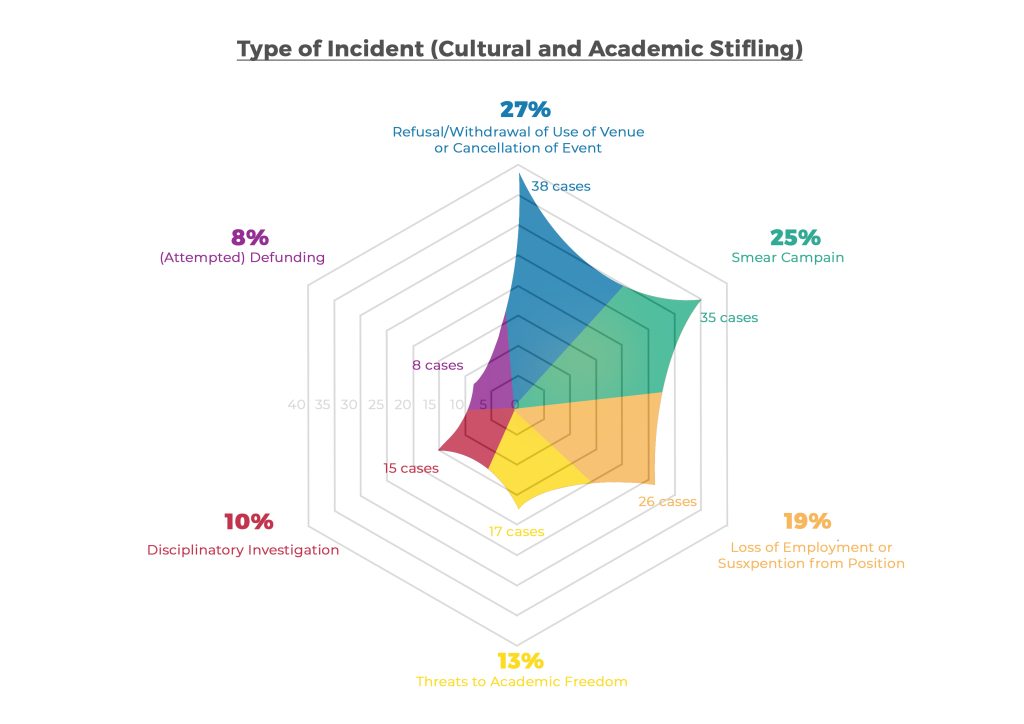

The ELSC recorded 139 instances of cultural stifling in the same period, including 38 instances where access to venues was withdrawn or events were cancelled, 35 instances of smear campaigns, and 8 instances where threats of defunding were made for expressing views on Palestine. Academic freedom was compromised in 17 instances, limiting the ability of scholars, researchers, and academic faculty to freely share research, information, and ideas related to Palestine and Israel. Additionally, 15 individuals or groups were subjected to formal complaints based on baseless accusations of antisemitism due to their advocacy or expression of support for Palestinian rights through social media posts, speeches at protests, podcasts, literature, or talks. The ELSC also identified 26 cases where individuals were either terminated from their jobs or suspended for their vocal support for Palestine. This intimidation, censorship and silencing in cultural and academic institutions and beyond not only undermines basic rights of free speech and academic freedoms but also prevents any meaningful space for critical reflections, (un)learning and discussion on Israel/Palestine.

The repression, censorship and exclusion against Palestinians in Germany is not merely a reaction to the events of 7 October, rather it has to be understood in its historical context, one in which Germany has continuously tried to not only repress Palestinian voices but engage in a wide range of practices and strategies to erase Palestine and Palestinian life in the country.

Systemic erasure

The Palestinian community in Germany has evolved significantly from its initial composition of students, workers, refugees from Lebanon or political exiles. This group has expanded over the years, becoming one of Europe’s largest Palestinian communities with an estimated population of 250,000. Berlin alone is believed to be home to between 35,000 and 45,000 Palestinians.

However, exact figures are difficult to determine because Palestinian citizenship does not exist in the German official statistics. Since Palestine is not recognized as a sovereign state in Germany, Palestinians often find themselves categorised under various statuses including labels such as refugees, stateless individuals, or persons of undefined nationality. Additionally, their migration records frequently link them to their countries of transit like Lebanon, Syria, or Jordan, instead of their Palestinian heritage. Not to mention Palestinians holding Israeli citizenship, who are typically registered as Israelis, or those with German or European citizenship.

As a result, official figures suggest that there are only 6,315 Palestinian nationals in Germany as of 2022, and it’s also worth noting that in 2020 the national category of “Palestinian territories” disappeared from the statistical reporting of the foreign population in Germany.

This ambiguous categorization of Palestinians in Germany not only obscures accurate data and knowledge about Palestinian life in Germany, but also contributes to their historical and systemic exclusion and marginalization. As part of the politics of erasure that renders Palestinians invisible, it negates their collective identity and existence and disguises their history, pain, achievements and significance in German history.

A long history

Understanding the Palestinian enduring resistance in Germany is pivotal, especially in the context of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO)’s formation in 1964. The PLO, which operated predominantly in the centres of the diaspora, played a crucial role in the Palestinian national project. Germany served as an important base for the PLO, with key founders like Hani Al-Hassan and Abdallah Frangi having lived and studied there. In fact, networks of Palestinian students, professionals, and workers in the country were integral to the global structure of PLO resistance.

However, for a long time, Palestinians lived almost unnoticed by the public. This changed with the attack on the Israeli team at the Olympic Games in Munich in the fall of 1972, when Palestinians became a hyper-visible figure and an embodiment of terror, threat and suspicion. As a result, the Ministry of Interior introduced tightened visa restrictions for Arab countries with interior ministers of the federal states deciding to speed up the deportation of Palestinians, leading to hundreds of expulsion orders issued against citizens of Arab states without legal basis. The General Union of Palestinian Students (UPS) and the General Union of Palestinian Workers (GUPA) were also banned in West Germany.

Politically active Palestinians faced increased surveillance and interrogation, marking a significant shift in their perception and treatment in West Germany. The repression and violence against Palestinians in the 1970s created a climate of fear and control, resulting for many in a denial of their Palestinian identity to the outside world in order to avoid discrimination, persecution or exclusion.

As Sarah El Bulbeisi, a researcher who has studied the Palestinian community in Germany, argues, the colonisation of Palestine, and the attempt to erase Palestinian life, society and identity, continues in Germany through symbolic violence in the form of discrimination, censorship, persecution and surveillance. She notes that “the taboo is so powerful that not only the experience of violence suffered by Palestinians but also being Palestinian per se becomes something socially condemned”.

Racism and Orientalism

What El Bulbeisi speaks about has been most clear in the past two years when collective commemoration and mourning of the Nakba in public spaces have been repeatedly banned by the police in Germany.

For Palestinians, the Nakba marks the destruction of historical Palestine and the ethnic cleansing and permanent dispossession of the Palestinian people, engendering a collective memory of loss, displacement and the beginning of ongoing struggles for statehood and rights. For the Palestinian diaspora, collective mourning is not only a way to express enduring grief, but also a process of healing, remembering and cultivating a community in exile.

In May 2022, the organisers of Nakba commemoration events in Berlin were served with a letter from the local police, banning all planned activities from 13 to 15 May. According to Palestine Speaks, one of the organisers, the Berlin police justified their ban with two arguments: first, the Palestinian diaspora as well as “Muslim communities, (…) presumably from among the Lebanese, Turkish as well as Syrian diasporas and (…) especially youths and young adults are considerably tense and emotionalized”, and, second, the Nakba commemoration events could be a potential threat to public safety.

The German state and police, hence, construct an orientalist threat that combines violence, emotionality and antisemitism in the figure of “young angry Arabs/Muslims”, which emerges in tandem with an imagination of the rational German-Self that has successfully rid itself of antisemitism and violence.

As the renowned Palestinian public intellectual Edward Said, pointed out in his seminal work ‘Orientalism’: “the notion of a distinct culture […] always get(s) involved either in self-congratulation (when one discusses one’s own) or hostility and aggression (when one discusses the ‘Other’)”.

In other words, the construction of a peaceful, tolerant and anti-antisemitic German-Self relies on the contrasting portrayal of a violent, intolerant, and antisemitic Muslim/Arab “Other.” This binary framework serves to obscure the complex historical and indigenous origins of antisemitism and its contemporary manifestations in Germany, particularly given that in 2022, right-wing extremism accounted for 84 per cent of antisemitic crimes.

The British-Australian feminist writer and scholar, Sara Ahmed, contends that this notion of potential threat, or “could-be-ness,” creates a shadowy figure of danger detached from specific individuals, yet “fear sticks to these bodies (and to the bodies of “rogue states”) of that ‘could be’ terrorist.” Fear of the “could be Arab or Muslims terrorist/antisemite” becomes a powerful tool used to legitimise security measures, mobility control, and justifies racially charged narratives within the country’s media discourse, policies and practices.

The necessary Other

The 7 October attacks reignited this orientalist narrative in media and political discourse, arguing that Germany has an ‘imported antisemitism’ problem, brought into the country by refugees and migrants, especially from Muslim or Arab-majority countries. German politicians across the political spectrum quickly called for ‘massive deportation’ or restrictions to citizenship and immigration.

For instance, expressions of support for the Palestinian cause have been used as justification for refusing to renew residency permits. Additionally, the latest draft of the naturalisation laws identifies antisemitic attitudes as a basis for exclusion, while also stipulating the recognition of Israel’s right to exist as a prerequisite.

Germans of Muslim and Arab origins are publicly called out by the German vice-chancellor Robert Habeck and President Frank-Walter Steinmeier to show their ‘loyalty’ by condemning Hamas violence, holding them collectively responsible for actions that are not their own.

This attribution of collective blame happens at a time when the German far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD) ranks second in the current polls, a party whose leading figures are openly aiming for a National Socialist-oriented reign of violence.

This is not only a targeted stigmatisation of these communities but rather a racism that functions as part of a larger structure and history. This binary opposition is crucial for German identity formation, where historical ethno-national understanding of the nation is predicated on a clear demarcation between the ‘native’ and the ‘other’, perpetually casting migrant communities as eternal strangers.

For people of Muslim faith and those labelled as Muslims, exclusion, discrimination, stigmatisation and sometimes physical violence are part of everyday life. Since 7 October , the Alliance Against Islamophobia and Anti-Muslim Hate (CLAIM) has observed a worrying rise in anti-Muslim incidents in Germany, documenting 187 cases of violence, verbal assaults, threats, and discrimination against Muslims between 9 October and 29 November 2023.

Steadfast defiance

The persistent suppression, marginalisation and negation of the Palestinian community in Germany, especially evident since the events of 7 October are indicative of a broader historical struggle for collective recognition and fundamental rights.

Throughout history, the attempts by the German state to erase the existence, visibility, voices and narratives of Palestinians in the country have been challenged by a strong mobilisation of solidarity and resistance. In the 1970s, the ban on Palestinian associations and the wave of deportations, sparked a left-wing solidarity movement calling for the protection of the rights of migrants in West Germany.

In contrast to their parents and in reaction to increased symbolic violence, second-generation Palestinians in Germany, are more and more re-appropriating their lost history and identity, exploring their family stories, and engaging in activism to reclaim visibility and foster a self-owned Palestinian narrative in the country. The 2015 refugee governance crisis established Berlin as a hub for Arab communities and cultural expression and made it possible for Palestinians of the second generation to connect with Palestinians who have been exposed to differing cultural, social and political contexts.

The last months also witnessed tremendous acts of resistance and solidarity. Demonstrations were organised by collectives that centred the Palestinian question in the broader struggle for decolonisation, justice and global solidarity. From organising spontaneous demonstrations, mass sit-ins, student-led protests and performative interventions at universities to wearing the keffiyeh as a symbol of resistance.

Across the streets of Berlin, one finds stickers, graffiti and paintings of flags and slogans, reclaiming public spaces and visibility while challenging the dominant narratives and historical erasures. Almost every day, there are teach-ins, community discussions, film screenings as well as musical and dance performances that bring Palestinian culture, heritage and history into the public space in the city.

From the reclamation of cultural symbols to solidarity movements and public demonstrations, these acts of resistance signify a burgeoning collective consciousness among Palestinians in Germany. Palestinians are challenging the dominant narratives and historical erasures and forging a path towards reclaiming their space, narrative and existence. As the Palestinian film director Pary El-Qalqili stated in her speech at the Internationalist Feminist Alliance demonstration against gender-based violence on 25 November 2023:

“We, Palestinians here in Berlin, are the daughters, sons and grandchildren of the survivors of the Nakba! Palestinians, whether in Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria or in the diaspora, have been witnesses to the ongoing Nakba for generations! But we have always stood up again! And here in Berlin, too, we have stood up time and time again when they denied us education and work, issued chain deportations, banned our associations, took away our spaces, criminalised our protests, arrested us and threatened us with deportation. We Palestinians stood up again and again and we are still doing so today.”