On 1 November 2023, in the midst of the ongoing Israeli war on Gaza, physicians Ghassan Abu Sitta and Rupa Marya published an article entitled “The deep medicine of rehumanizing Palestinians” in Yes magazine. The article, submitted to and rejected by the British Medical Journal, was written from the operating room of Al Shifa hospital. Three weeks into the war, the two physicians addressed the detrimental effects of dehumanization taking place in Palestine, a process that allowed for the brutal bombing of hospitals, universities and neighborhoods, and the unlawful blockade of water, medicine, and food to continue. Abu Sitta and Marya write:

“Dehumanization is part of the colonial process and is the prelude to massacre. The use of this language is the heralding event we must recognize in order to intercept and collectively intervene to prevent genocide”

The physicians then focus on the neuropsychological effect of dehumanization on the mind:

“Such language switches on neural circuits that bypass our cognitive centers, steering our minds in ways that fix beliefs over time, proving difficult to change even in the face of contradictory evidence”.

Dehumanizing language, such as referring to Palestinians as “human animals” and to Palestinian children as “children of darkness” is therefore no small detail. It has a neuropolitical effect, and materially makes way for genocide. Languages of dehumanization normalize violence and render unfathomable massacre invisible, mundane, banal, reminiscent of playing video games, and a well-deserved form of punishment for human-animals. As Gaza becomes a site for military experimentation with new drone technologies, dehumanization in the battlefield also takes on a technomoral form, with drones programmed to take on tasks that include watching, killing and even addressing civilians.

For the last four months, this work of dehumanization has extended beyond the battlefield and Israeli politics to include European and North American policies of silencing and policing Palestinian voices and symbols, including protestors and activists, artists, academics, union workers, social media users, and other professionals, particularly in Germany.

In their article, Abu Sitta and Marya call for a reshaping of the ethical role of physicians in times of dehumanization and genocide. They argue that it is the duty of physicians to rehumanize Palestinians, and they connect the process of rehumanization with decolonization, an overused term that has come to mean nothing more than an intellectual muscle flexing in ‘politics’ in academia, yet remains an urgent praxis in the lives of people in settler colonies and post-colonies today.

Rehumanization according to the two physicians is then “an important exercise for the world to engage in”. It brings us a step closer to justice, and to survival from colonial and imperial violence. It is a form of neuropolitical rewiring, a work of reimagining healing, life, and liberation of bodies and minds:

“Whereas dehumanization trains our neurons to accept atrocity, rehumanizing can expand our vision to see healing realities that lie beyond the current limits of our imaginings.”

Departing from the physicians’ call that “the work of rehumanization is the medicine we urgently need”, I ask: how can we, as mental health workers, understand and deal with the psychic suffering that ensued from the systematic extermination and forced displacement we are witnessing in Gaza and Palestine, both in and outside the clinic?

How do we listen to and conduct therapy for a form of suffering that is barely acknowledged, recognized, and permitted to surface globally, and many times even regulated and violently silenced? How does one heal, and become rehumanized in a dehumanizing world that is hardly able to see their suffering, no matter how brutal, and no matter how much evidence of it there is?

In other words, what happens when we center the work of rehumanizing Palestinians, as a psychopolitical path towards reimagining new mindful bodies who are seen and heard wholly, mindful bodies who matter, who have the chance to survive and rebuild, who are protected and loved, and who are free? How do we rehumanize on a material, psychological and communal level?

To rehumanize is to break off with the trauma/ resilience framework of suffering

So far, the framework that makes suffering legible—a suffering that we can identify and sympathize with—is the framework of trauma/resilience, a western and globalized binary of suffering that is appropriated and contested in various local sites. It circulates through humanitarian and psychiatric institutions, as post-traumatic-stress disorder (PTSD) and trauma on one hand, and psychological resilience in the face of violence on the other.

Yet, the issue with this framework is not its cultural specificities— in that it does not “fit” and is not compatible with a certain Palestinian culture. The problem lies not in the supposed cultural differences of how people experience violence, but in the political and economic instrumentalization of this framework to position suffering in the global landscape. In a world where one must fight to prove that one is indeed suffering, to literally fight for visibility, the trauma /resilience framework, even in therapeutic clinics, sounds prescriptive and more like a global stamp of approval.

Does trauma rehumanize?

Trauma—in its many elusive forms— has become the quintessential global object of suffering, constituted by humanitarianism and psychiatry as the psychological entry into the human experience of violence, torture, war and injustice. In these discourses, trauma is considered a form of moral witnessing to violence’s detrimental atrocities and a compass for a modern, shared and empathic humanity. Trauma is ‘the stuff’ of what makes us, all of us, human, these discourses claim.

Yet, PTSD and trauma from Israeli violence have been well critiqued and challenged in the Palestinian context as imperialist, apolitical and incompatible with the temporality of violence in settler colonial and refugee contexts. In the Lebanese context, trauma from Israeli violence also appears to be part of psychological warfare rather than an expression of its aftermath and has infrastructural and ideological underpinnings.

The political incompatibility of trauma to represent injuries from Israeli violence has been further employed to assume that there is a general absence of suffering from this violence. On the Israeli side, however, PTSD cases in soldiers have always been easily identified. The discrepancies in PTSD cases have been used and claimed by Israeli journalists, politicians and others as a way to further dehumanize Palestinian and Lebanese, representing them as people who do not suffer, who are used to violence, whose bodies are not modern or civilized enough to be traumatized, and whose culture is a culture of death. After all, a human-animal does not get traumatized, nor does it have the civility to suffer from bombs, militarization and massacres.

Trauma from Israeli violence is therefore an integral part of the battle over suffering and victimhood, that we see unfold today in the ongoing genocide. It has always been present in Israeli wars in the form of psychological warfare and has been employed to further dehumanize Palestinian and Lebanese bodies and minds.

A process of dehumanization, then, takes place within the framework of trauma, and I, as a survivor of Israeli violence, a mental health practitioner, a scholar and a patient of therapy, have grown to really dislike this framework. Trauma feels like wearing a school costume everyday to ‘fit in’ the global landscape; an imposed frame that posits itself as the only way to truly suffer. Yet when experiencing Israeli violence, trauma is clearly ideological. It is not about rehumanization.

One epic example of how trauma from Israeli violence further dehumanizes Palestinians and Lebanese is the movie Waltz with Bashir, an Israeli adult animated movie addressing the war trauma suffered by Israeli soldiers as they invaded Lebanon in 1982 and participated in the Sabra and Shatila massacre, when 2000 to 3500 palestinian refugees were killed, tortured and mutilated in two days. The movie depicts the psychological journey towards healing of an Israeli soldier as he recounts to his therapist his memories of the 1982 invasion, arriving to a kind of catharsis when he succeeds to remember and speak about his role in the massacre.

The movie ends with a move from animation to real life, as we turn to see the actual massacre, represented in the movie by a Palestinian woman screaming in Arabic, her voice apparently untranslatable, because there were no English subtitles to her cry in the cinema theater in Ann Arbor Michigan, where I saw that movie in 2008, at the beginning of my PhD studies (ironically, the woman was calling to the camera to film the massacre and send it to the foreign countries for them to see).

I still remember the beginning of that movie. I remember seeing animations of empty bags of chips, and stray dogs barking in the streets of Beirut. I will never forget how painful it was to watch this movie as it erased the war that formed my own psychological pain as a six-month-old baby; the invasion and subsequent Israeli occupation of South Lebanon that prevented me from seeing my grandparents until the age of two, that framed my childhood. My war.

Lauded as an anti-war movie, Waltz with Bashir managed to rehumanize the Israeli soldier while erasing any voice of suffering from the Lebanese and Palestinian side, turning them unrepresentable and undecipherable in the trauma discourse. A complete inability to recognize, narrate and represent Palestinian suffering from the Sabra and Shatila massacre.

Ironically, Waltz with Bashir (2008) registers this ‘absence’ of trauma and indifference to violence in one scene, also a ‘true story’ of an Israeli journalist accompanying the Israeli military during the invasion of Beirut, who notes his shock and surprise at the sight of Lebanese people watching the invasion and the bombing from their balconies and not hiding in shelters. The movie represented, yet again, the Lebanese as essentially and almost naturally indifferent and unaffected by violence.

If not trauma, then does resilience rehumanize?

One might interpret the movie’s representation of Lebanese standing at the balcony watching the invasion as a form of resilience, or ‘Sumud’, a Palestinian psychopolitical form of steadfastness, resistance to violence, oppression and colonial occupation in everyday facts of life. ‘Sumud’ has been imperative and integral to Palestine resistance and communal survival throughout the years and is part of Nakba knowledge, a visceral and intergenerational knowledge about how to survive from Israeli genocide.

‘Sumud’ can properly represent the work of survival in oppressive and colonial contexts, and reveal communities’ agentive positions. Yet, resilience, as a dual side of trauma— i.e. if one is not traumatized, then one has psychological resilience and is not affected by the violence experienced—has the capacity to dehumanize, since it represents Palestinians as purely heroic subjects whose suffering, again, remains invisible and unrepresented.

Perhaps one example of how ‘Sumud’, when ideologized, can dehumanize Palestinians, is the sexist comment made by Lebanese daily Al-Akhbar’s editor in chief Ibrahim Al-Amin that Palestinian pregnant women can reproduce the massacred populations in a matter of two months. While Al-Amin framed his comment in the context of liberation movements’ steadfastness, this form of de-humanization sadly echoes how Israel refers to the bodies and minds of Palestinians as uncivilized and devoid of suffering. A second example is the rising interest in psychogenetic research to study and understand the resilience of Syrian and Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, viewing ‘Sumud’ almost as a naturalized form of difference.

If we were to take rehumanization as a central focus in our understanding of suffering, neither of the trauma and resilience binaries are suitable frames for this process.

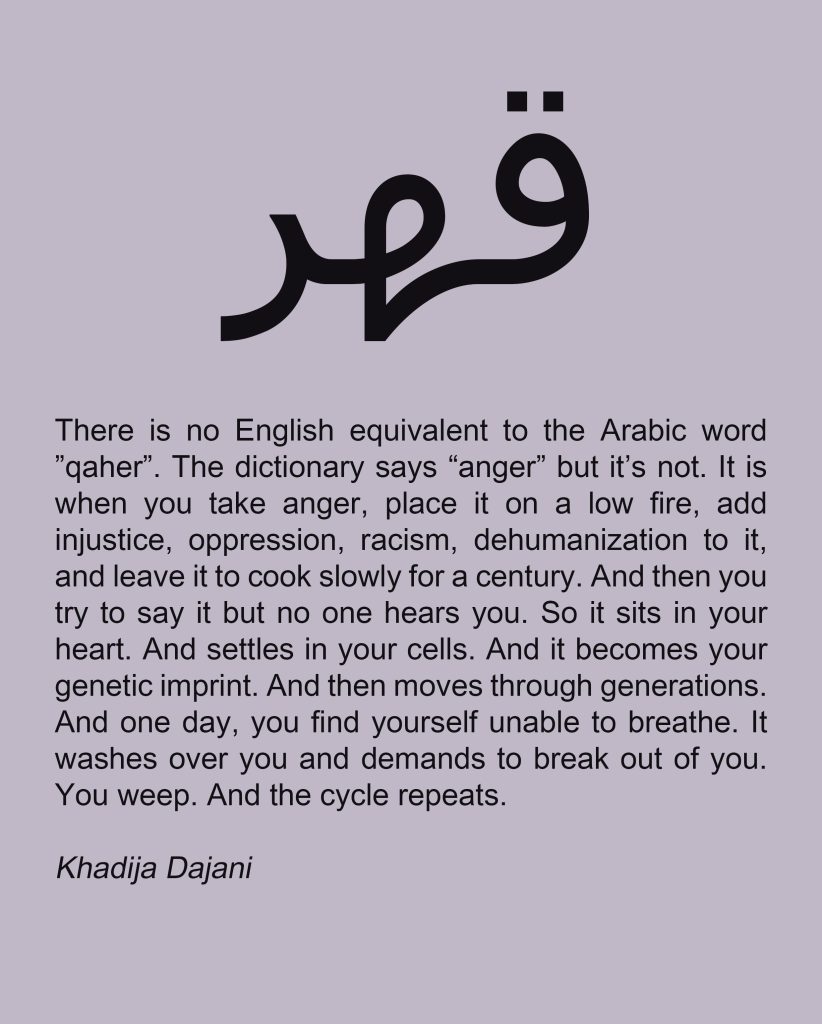

In my earlier reflections on violence, suffering and healing after the Beirut port explosion, I argued to move away from the trauma/resilience binary, towards attending to the ways of surviving and rebuilding, and to apocalyptic empathy: a radical form of affect at the end of the world. These reflections, inspired by the work of Black American science fiction writer Octavia Butler, were a call for reimagining and rethinking what it means to be human, beyond centering suffering as the site of humanity. They focused on what it means to survive and recover in radical times, with its complex emotional landscape of happiness, guilt, deep mourning, numbness, living-as-dead, disgust and ‘Qahr’ قهر.

Rehumanization and decolonization: rupturing with the global, piecing back the local

As more than eighteen “humanitarian states” have moved to defund UNRWA, and as the genocide continues in its four months, I also write from a place and desire of rupture with global frameworks that are militarized, part and parcel of humanitarian global community, yet are unable to account for suffering in contexts of settler colonialism. My desire for intimate local spaces of healing is a visceral one; spaces where we share knowledge about the pain from Israeli violence, about the persistence and dwelling in survival, about making lives matter in unlivable spaces, and about mourning and grieving.

These are the intimate and local spaces of rehumanization that we have, alone and together. To rehumanize Palestinians is to rupture with the global rather than stay ‘connected’ while holding a feeling of disillusionment that I know echoes among many, as if we are living on two different planets. To rehumanize is to work with our local knowledges intimately, on both bodies and minds.

Writing this piece, I remember an interview I conducted in 2022 with Dr. Ahmad Dieb in Tunisia, in the framework of my research on the project of postcolonial psychiatry and medicine in the Middle East and North Africa. Dieb, a Tunisian surgeon and physician who took part of the Arabization project of medicine and psychiatry after French colonialism, had curated and established Tunisia’s first museum of Arab medicine.

During the interview, conducted in classical Arabic, Dieb spoke about how he traveled to different countries in the Arab region to locate the various surgical tools used in Arab medicine, whose history far precedes European medicine, and whose many inventions and knowledge has been lost and fragmented due to colonialism. When he could not locate the actual tools, or when he could not find funding to retrieve them, Dieb made a replica of them himself, based on historical records. He also turned into a painter, recreating, with the help of professional painters, many historical paintings representing Arab medicine.

I was struck by his deep commitment, and by this act of love from a physician whose role was intuitively one of re-enactment of the history of Arab medicine. I asked him, why would a physician go into so much trouble to reproduce historical tools and paintings of Arab medicine, almost becoming a painter and a sculptor himself.

He answered loudly, his pain so tangible that we both teared up:

“لكي ألملِم شتات نفسي”

“So that I can gather back the pieces of my self.”

Moved by his response, I wondered then what the political and moral values this arabization project of psychiatry and medicine has in the twenty-first century, viewed as somewhat conservative and isolationist in its return to indigenous knowledge.

I can clearly see now that Dieb’s work is itself a work of mending knowledge and culture back into visibility. I can viscerally understand why this physician would go into all this trouble, and I relate to this decolonial moment anew as a mental health practitioner trained in European and North American skills, with my own soul fragmented today into so many pieces.

While Israel, supported by western powers, engages in the act of epistemicide–another process of dehumanization that wipes out entire knowledges and ways of being and belonging–Dieb’s work is itself a work of rehumanization, and resonates so powerfully with the call of physicians Abu Sitta and Marya.

These older moments of decolonization are about the work of piecing together the soul and the self, an act of a psychological, political and communal rehumanization. They are moments of both rupture and rebuilding, an intimate and private detachment, a rebuilding without. Without the international community, without having to translate one’s pain, without fighting to appear visible, without having to provide evidence.

As we rethink what rehumanization means on an emotional and psychological level, as we retreat into our intimate and visceral spaces, I ask us to disentangle ourselves from the global binary of suffering and focus more on the work of mending and recovery that surrounds us in these radical times, and attend to its complex and contradictory affect.

Alone and together, we carry this pain without, and rehumanize it.