In 1978, the German institution “Munich Re,” specialized in risk management, issued the first report assessing natural risks for most regions worldwide. The report applied the concept of natural risks as an umbrella term that includes earthquakes, volcanoes, storms, floods, and other natural disasters. During the past few decades, there has been an increased interest in the assessment of natural risks as a field of research and practice on a broad international scale, driven by the climate change crisis and the increasing frequency of natural disasters around the world. We can draw the conclusion from these studies by stating that we live on a planet whose climate, biodiversity, and geology are imbalanced, and we must predict and prepare for more occurrences of extreme weather, droughts, floods, and other natural dangers. According to the United Nations Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction, the number of natural disasters globally increased annually from around 100 disasters in 1970 to 400 in 2015, with expectations that they will rise to 560 disasters by 2030.

Syria is positioned 44th out of 190 countries in the ‘World Risk Report 2023.’ This annual report evaluates the probability of regions facing exposure to natural disasters based on scientific data. It also measures the impact on communities and the ability of countries and communities to resist and recover from disasters. In Syria’s case, while the likelihood index of exposure to disasters is not extremely high, indicators of fragility, vulnerability, and a weak ability to adapt were among the highest on the scale. This places Syria ahead of Vietnam, which is recognized as the country most prone to natural disasters globally.

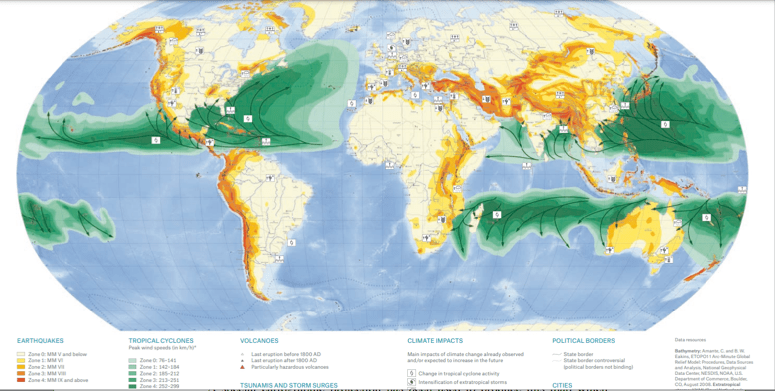

Figure 1 – Map of Natural Risks Worldwide (Munich Re Foundation, 2011)

This article raises a question about the extent to which the experience of the February 6 earthquake in Syria has contributed to encouraging and potentially strengthening the resilience of local communities to natural risks in general. The article will present images reflecting various aspects of societal resilience observed in different regions affected by the earthquake. We will emphasize observations that depict three levels of resilience, as categorized in the literature: the capacity to absorb the initial shock and adjust to natural disasters without societal collapse; the capability to deal with significant changes brought about by disasters and prepare for their ensuing consequences; and lastly, the ability to accomplish institutional transformation that addresses challenges in a high-risk environment.

The ideal portrayal of a disaster-resistant society in the era of climate change incorporates material aspects like infrastructure and developmental levels in nations. It also encompasses a socio-cultural aspect manifested in people’s awareness of natural risks and the utilization of that awareness in daily behavior and practices. Lastly, and most importantly, it includes an institutional aspect that assumes natural risks require specialized and innovative regulatory frameworks to deal with them. Below, we highlight the most notable changes observed at the social and institutional levels one year after the earthquake.

Housing Changes

Throughout the years of conflict in northwest Syria, residents have grown accustomed to residing in the innermost rooms of their homes to offer enhanced protection against aerial bombardments. They also got used to securing both external and internal doors with double locks due to deteriorating security conditions. Both of these measures made sense when the innermost rooms of the house were considered safe. However, with the earthquake and weeks of subsequent tremors, the path of exiting the house to the street and the time it takes for the process became critically important. Omar (35 years old, Idlib countryside) a father of two, explains: “Now we prefer spending time in the rooms closest to the exits. We ensure there are no obstacles in our way, like locks that take time to open. We still keep an emergency tent, and until recently, we had a bag called The Evacuation Bag containing food, clothing, and essential tools.” Such tactics that people learned in earthquake-affected areas constitute the first level of societal resilience, which we can observe in other manifestations, such as the reinforcement of buildings. Even those unaffected by the earthquake are now being fortified with additional supports and concrete structures on a wide scale. This movement has been widely noted in the city of A’zaz and surrounding areas, as reported by local residents. While the main incentive for these actions is property owners’ desire not to lose their assets, they significantly contribute to enhancing the resilience of urban structures in those areas. People, in general, have become more aware of construction standards, and real estate.

On the other hand, we noticed the preference of residents in the areas affected by the earthquake to live in single-story buildings or structures with a few floors rather than high-rise buildings. Most people see multi-story buildings as more dangerous because exiting them is much harder. This has impacted the real estate market and rental values, as Hassan (29 years old, A’zaz city) states: “I used to pay a hundred dollars per month for my apartment on the fourth floor in Mare’ before the earthquake. Today, I only pay sixty dollars… the building owner reduced the monthly rent after I started looking for a ground-floor house. He wanted me to stay in the apartment because it became hard for him to find new tenants.” In contrast, rents for rural homes and old Arab-style houses have increased. Of course, the housing crisis resulting from ten years of war and internal displacement that intensified after the earthquake does not allow the luxury of choosing between high-rise apartments and ground-floor houses for the vast majority of residents in those areas. Many are forced to live in buildings that are terrifying for them. Laura, 27 years old, who experienced the earthquake in Latakia and participated in civil response operations, says: “People were very sensitive to building safety and safety measures in the first months after the earthquake. However, many of them later slackened under the pressure of the need for housing and rising rents, returning to their previous lives but with greater fears.”

On the societal level, it can be said that many precautionary measures have become a part of people’s daily lives, and changes have occurred in the concept of a safe house from a home that shelters you from external risks to a place you can easily exit. This form of collective adaptation has occurred spontaneously through direct individual learning and constitutes an important part of the community’s resilience to risks. However, sustaining the outcomes of these adaptation processes and socially embedding them requires the existence of institutional and governance structures capable of learning from the lesson provided by the February 6 earthquake and leading a multi-level transformative process toward a more disaster-resistant society.

Changes in the Public Sphere

As for the UN aid system in Syria, a key player in managing the response, the writer and humanitarian response expert, Mohamed Katoub, argues that the UN aid system, which increased the fragility of situations in northern Syria before the earthquake, remained the same afterward. In other words, even after the United Nations acknowledged the failure of its system to deliver aid to northwest Syria during the critical days following the earthquake, no significant changes have occurred in that international mechanism a year later. Instead, aid has been reduced from 2.3 billion in 2022 to 1.9 billion for 2023, later supplemented by a special earthquake aid package of 0.4 billion US dollars, bringing the total aid to the previous year’s level. In general, the behavior of UN agencies and other international organisations remains more connected to the policies of their donors and the international context in which they operate than to developments on the ground in Syria. More important in a case like Syria are the changes that may have occurred in the approaches of the local governing authorities, both in areas controlled by the government or the opposition, as well as for the more active civil society in opposition-controlled areas.

In both government-controlled and opposition-held areas, Syrian local communities absorbed the majority of the initial shock of the earthquake. Later, authorities and organizations intervened in different ways in each area. While the government utilized its security and administrative state institutions, as well as its affiliated “non-governmental” entities, to control and monopolize the response and aid operations that poured in from abroad, non-governmental organizations played a major role in opposition controlled areas amid weak governance structures there. In this context, the White Helmets organization stood out, playing a crucial role in leading thousands of volunteers from civilians, faction fighters, and humanitarian workers during the critical 72-hour rescue operations. This occurred at a time when international aid and rescue teams were only reaching the affected areas controlled by the government. In addition to the Civil Defense efforts, several large Syrian organizations were active in the earthquake response.

On the institutional adaptation level, a notable action can be observed in opposition-held areas following the earthquake, as three major Syrian humanitarian organizations—the Civil Defense (White Helmets), the Syrian American Medical Society, and the Syrian Forum formed an operational alliance to coordinate earthquake recovery efforts. These organizations announced that the alliance is open for further participation. Earlier, the interim Syrian government declared the establishment of the “Supreme Council for Disaster Management,” comprising government bodies, non-governmental organizations, and unions. By the end of the earthquake year, a new alliance was announced between the Civil Defense and the Amin Foundation for Humanitarian Support, targeting the healthcare sector. Regardless of the efficiency of these alliances and new entities—an aspect not explored for the purpose of this article—they can be considered indicative signs. On the other hand, it is challenging to observe such indicators in Latakia, Aleppo, and other government-controlled areas affected by the earthquake, where security dominance continues to hinder any structural changes in both the civil and governmental sectors. Except for the temporary response coordination operations dominated by the Syrian Development Trust in Latakia and Aleppo, there appear to be no new governance structures formed following the earthquake, neither on the civilian nor the governmental level.

A Look Ahead

The theory posits that achieving disaster-resistant communities requires economic, infrastructural, legal, social, health, and other measures that strengthen communities in the face of disasters and enhance recovery afterwards. Such transformation seems distant in the case of Syria, where the doors of war have not yet closed. While the country still hopes for a political solution that restores political stability and economic activity, the earthquake serves as a reminder for actors in the Syrian scene that they also need to reassess the natural risks surrounding them from a perspective that incorporates various environmental hazards, not just earthquakes. The reality is that some natural disasters occurred before the earthquake, continuing afterward, including drought. The latest waves of drought began in 2021 and extended over the past three years, resulting in the depletion of half of the vegetation cover in crucial agricultural regions of the country.

For a society that has endured one of the worst war-related disasters in modern history, calling for preparedness for more coming disasters may seem overly exaggerated. However, learning lessons is the utmost we can take from the earthquake event. Consequently, having catalysts for projects that enhance the resilience of communities, such as the case of the Civil Defense and other humanitarian and developmental organizations active in opposition-held areas, increases the chances of progress there. But for government-controlled areas, the matter seems more complex, as there is a single locus of power setting policies that do not prioritize community strengthening.