“Boycotting is very often the most powerful thing we can do,” the British actress Tilda Swinton stated in a press conference at the 2025 Berlinale, the International Berlin Film Festival, where she was honored with an Honorary Golden Lion.

It is fitting then that Peter Wollen’s Friendship’s Death (1987), the one film that Swinton chose from her extensive filmography to be shown at Berlinale this year – a film centered on the very idea of boycott’s political efficacy and its ethical, humanistic urgency – was screened in the film program of On Strike Berlin, an alternative programme running parallel to Berlinale in various venues across the city.

Indeed,the program was organized collectively by On Strike: screenings & talks striking Berlinale to answer a call by Strike Germany and Film Workers for Palestine to boycott this year’s Berlin Film Festival. On Strike cites numerous reasons on its website for joining the boycott. Among them the German state’s foreign policies pertaining to Israel’s assault on Gaza, German politicians’ backlash against expressions of solidarity with Palestine, and the events that took place at the 2024 Berlinale, including the recriminations in Germany against the Israeli documentary filmmaker Yuval Abraham and the Palestinian filmmaker and activist Basel Adra, the co-creators (alongside Hamdan Ballal and Rachel Szor) of the searing documentary No Other Land (2023), documenting the displacement and destruction of Palestinian homes by the Israeli army in Masafer Yatta, in the occupied West Bank.

The film won Berlinale’s Best Documentary award and subsequently the Best Documentary award from the American Film Academy at the Oscars, yet faces censorship and reprisals as it screens globally.

To counter this climate of silencing voices speaking against the decimation of the Gazan population, the illegality of forced displacements, and against Israel’s assaults, as well as to create a richer climate of discussion about the ongoing occupation of Palestine, the screening of Friendship’s Death featured special guests: British film scholar Nicolas Helm-Grovas (presently writing a book titled Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen: Towards Counter-Cinema) and Palestinian editor and educator Hazem Jamjoum, moderated by filmmaker Philip Rizk, to contextualize the film’s socio-political and historical context, and its present relevance.

The emergence of a political consciousness

Wollen’s Friendship’s Death tells the story of an extraterrestrial android called Friendship, sent to Earth on a peace mission. Friendship originally is meant to address the United Nations in New York, hoping to persuade humans to abandon their bellicose ways and their annihilation of all life forms. Much of Friendship’s journey to Earth is enclosed within the larger philosophical consideration of her quest for autonomy: A sophisticated robot – a futuristic AI – uploaded with advanced data and facts about Earth by her extraterrestrial creators, she nevertheless originally lacks the sense of self-determination. Not cognizant of having a choice to decide her own fate, she will only come to it slowly.

This aspect of self-determination and autonomy, mingled with Friendship’s undying fascination with and compassion for humanity, serves as the basis for Wollen’s launch into historical and political debates running throughout the film. In this sense, Wollen’s film is particularly urgent today, because its underlying theme is the emergence of a political consciousness, and the contrast between passivity and commitment, with Friendship’s android mind serving as a cognitive tabula rasa, in which this consciousness emerges.

The film’s historical backdrop is “Black September” of 1970; the action takes place in a hotel in Amman, Jordan, where Friendship lands, after her spaceship crashes mid-flight. Friendship loses her documents, suddenly becoming a non-entity: As an android, she’s trapped in the human shell, essentially undocumented, and stateless – a fact that immediately aligns her with all the Earth’s political outcasts, as all people denied their dignity, and their civic and political rights. This position gradually pushes Friendship from her original impartiality and wish to complete her mission to her alignment with the oppressed and the dispossessed; a stance that leads her to abandon her diplomatic mission and join the Palestinian cause.

Questions of solidarity

Friendship has only one close contact at the hotel: Sullivan, a British journalist who is covering the Middle East conflict, and is sympathetic to the Palestinian struggle. Friendship and Sullivan are stranded at the hotel, in the midst of Jordan’s civil war. This aspect of the film, in particular, gained much from the Q & A discussion, during which speakers framed it within international solidarity and the 1960s’ revolutionary movements.

Solidarity is indeed a motif running through the entire film. There are the limits of Sullivan’s solidarity, in the sense that his job is to report on the conflict, yet he doesn’t see the possibility of an immediate positive outcome, and, by the end of his stay sounds defeatist (Wollen’s critique of Sullivan aligns with the criticism that Adra makes in No Other Land of journalists expecting immediate resolution to a conflict spanning decades).

There is the clear theme of Friendship’s solidarity with humanity – her concern about its self-destructiveness, which makes her empathize with both the Palestinian and Israeli victims; an empathy which doesn’t preclude her recognizing that her peacemaking mission is bound to fail; she is more likely to be captured, and used by the US industrial complex to manufacture weapons of destruction, than she is to convince militaristic societies to abandon their quest for power. In this sense, while Friendship’s boycott of her mission is undershot by pessimism similar to Sullivan’s, it is uniquely linked to her acknowledging that she isn’t an innocent bystander; as a robot, she is part of the techno-military complex that perpetuates wars. Wollen clearly also means to say that we are all implicated in the foreign policies and territorial grabs of our governments.

The equally pertinent question of solidarity on which Wollen touches, explained in detail by Hazem Jamjoum during the film’s Q & A, lies with the Middle East: Friendship’s Death records a critical moment in Middle East history, when, after Jordan hosted Palestinians in the wake of the Arab defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War against Israel, the idea of Pan-Arab solidarity that had mobilized the region in the early ‘60s, giving rise to the idea that the Arab countries would liberate Palestine, comes to an end, as Jordan attacks Palestinian resistance fighters: “A crushing moment for the notion of the Arab revolution.”

Jamjoum also stressed in the Q & A that the student movements aligned with Palestinians, some formed into militant factions, were anti-authoritarian and anti-monarchist, which put them at odds with regressive Arab regimes. One might add that, in Europe, solidarity with Palestine was inscribed in an anti-colonialist, anti-imperialist, anticapitalist ideal, which also died in the 1970s.

Friendship’s answer to this collapse of solidarity is manifold. When questioned about her position on the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) hijacking planes, she commiserates with both the fear and suffering of the kidnapped, and the anger and desperation of the hijackers.

In a crucial conversation with Sullivan, Friendship relates how she ventured outside the hotel, to Jerash, a city in the North of Jordan, and was picked up and interrogated by the Jordanian Army Patrol, alongside her PLO escort. Friendship repeatedly confides her helplessness trying to ensure her escort’s safety; she fails as they are separated – a traumatic episode, which, not incidentally, coincides with Friendship identifying the hotel in Amman as “home” for the first time.

Similarly, in No Other Land, Abraham tries to safeguard Adra and others as the Israeli army bulldozes Palestinian homes, yet Adra’s cousin dies of a bullet wound after being shot by an Israeli soldier. Like Abraham’s, Friendship’s political consciousness evolves out of a profound sense of helplessness, and a growing awareness that the efficacy of her civilian actions is limited.

Can cinema forge a vision of solidarity, dignity and justice?

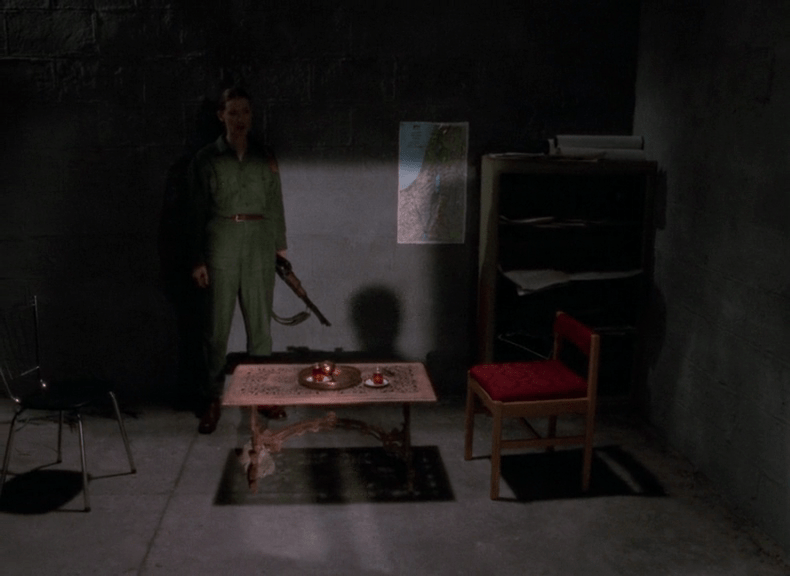

Both Sullivan and Friendship face choices with political implications: Sullivan returns to England; Friendship stays in Amman. Wollen shows her wearing a militant uniform, and in the voiceover, she is heard reading a note, hidden in her pocket, to her future killer. The film ends with Sullivan reminiscing about Friendship years later, in London, trying to watch a film she left behind, finally decoded with a more advanced technology. Yet Friendship’s file is an abstract puzzle of signs, in a way suggesting that humans still lack the wisdom to receive her message.

Lacking a coda, what remains of Friendship’s legacy is her choice to bear witness and her sacrifice – Wollen gives Friendship the most searing lines in the film, in which she expresses her desire for her existence to have meaning, looping back to the film’s ethical resonance. Friendship chooses to resist, but it is Sullivan who tells her tale, and his daughter who decodes Friendship’s film. In the end, Wollen’s film expresses a hope that cinema can forge a vision of solidarity, dignity and justice; or, to quote Swinton’s Berlinale speech, to be a vehicle for inclusion, making us consider “what sovereignty means to humans” – one of the most pressing questions of our time.