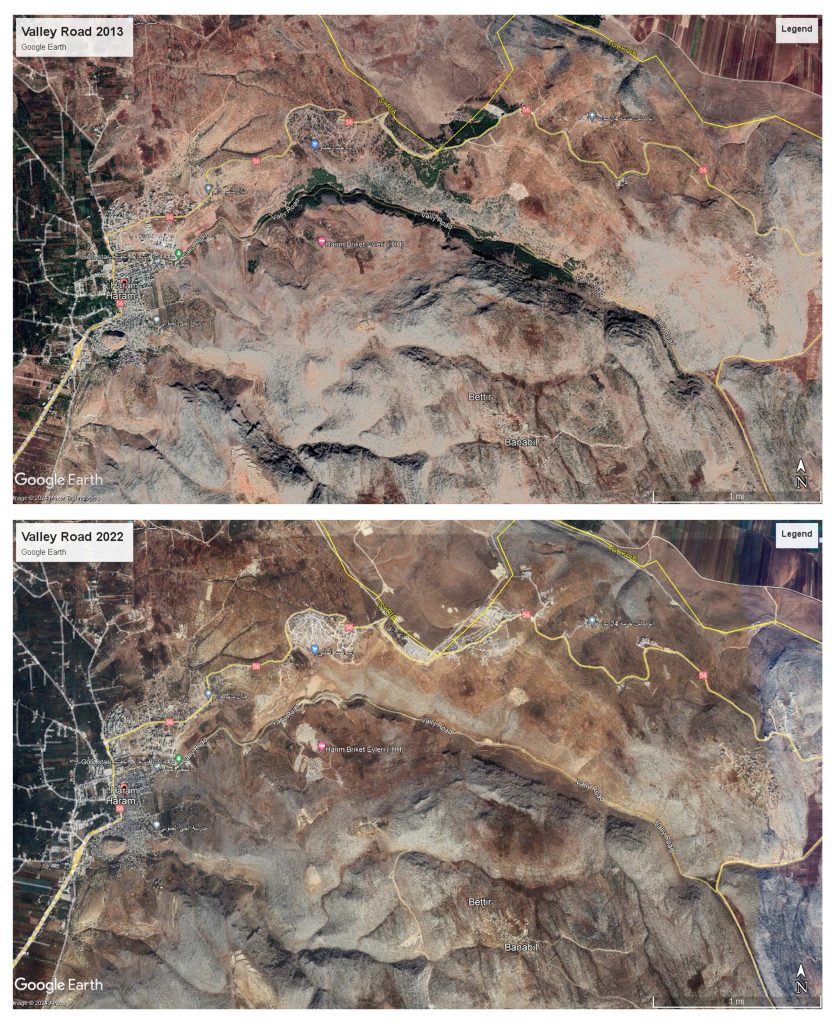

The “Valley Road” that heads eastward from the town of Harem to Sarmada, in the northwestern Syrian province of Idlib, winds between rolling hills covered with short-cropped grass, intensively grazed by herds of sheep.

A few years back, visitors driving through the area would have enjoyed a completely different sight. This scenic route sat in the thick shade of cypresses and pine trees, and at its edges the soil was greener, dotted with seasonal flowers and pine needles. Satellite images from 2015, captured on Google Earth, show long sections of the road sandwiched between two emerald belts of trees.

“The area around Harem used to be rich with cypresses and pines, especially as you head towards Aleppo on the ‘Valley Road’,” recalls 38 year-old Muhammad*, an aid worker who lives nearby. “But after people from all around Syria were displaced to Harem and its surroundings during the war, people began to deforest the area in order to heat themselves,” he adds.

Today, the forest has effectively been logged out of existence, and it is hard to believe that trees stood on these bald hills less than a decade ago.

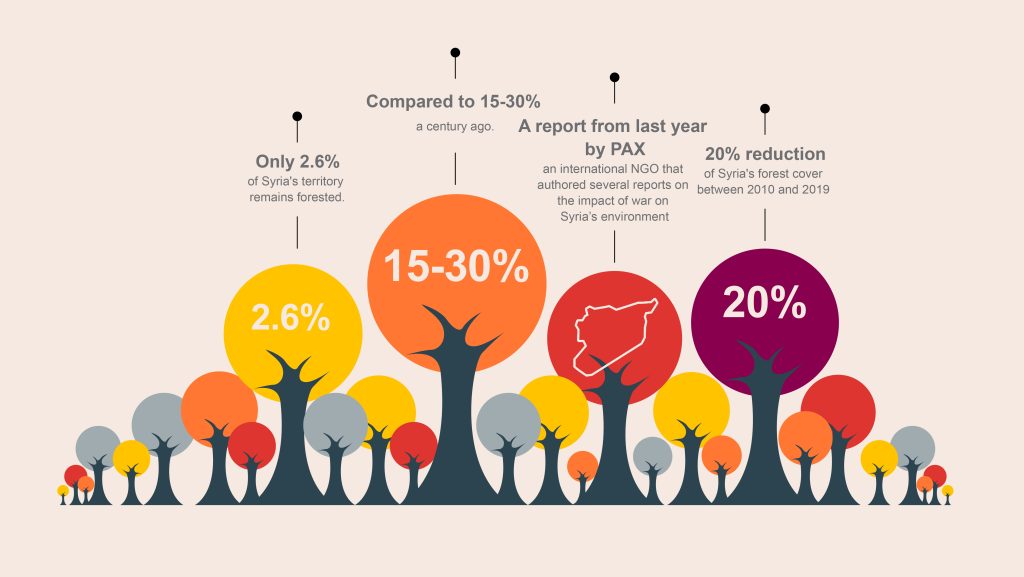

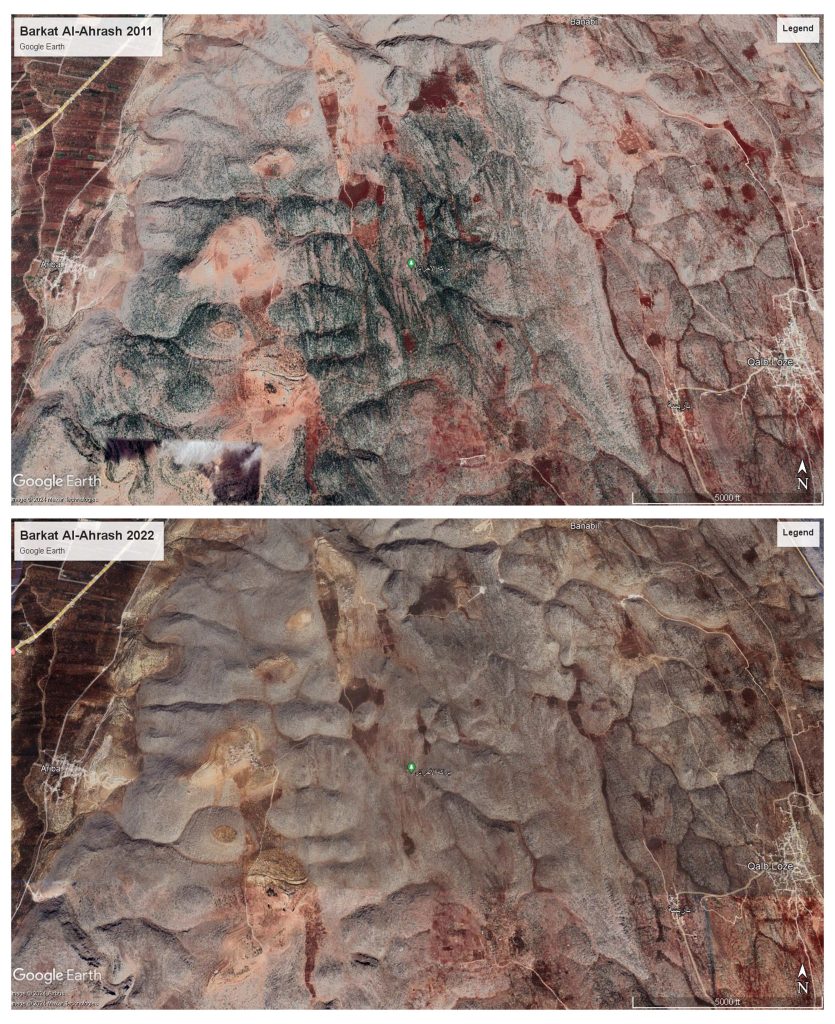

The story of Harem’s woods, eaten away over the years by illegal logging, is one among thousands in Syria. According to recent research findings in forestry, between 2010 and 2019, Syria’s forest cover shrunk by almost 20%. A report from last year by PAX, an international NGO that authored several reports on the impact of war on Syria’s environment, warned that only 2.6% of the country’s territory is still covered by forests, compared to 15-30% a century ago. But even these few surviving forests are in danger. Remote-sensing analysis by PAX also warned that 36% of the remaining natural forests – most of which spread over the western provinces of Idlib, Hama and Latakia – have been damaged between 2018 and 2020.

Unregulated logging, charcoal production and wildfires are some of the key factors that have fueled the decline of Syria’s forests during the war. In some areas, different parties to the conflict also accuse each other of deliberately looting the forest, of lighting fires or letting them soar out of control to achieve military goals.

Energy insecurity and rampant poverty

The damage to Syria’s forests is most visible in the country’s northwest and coastal areas, where nearly 80% of natural forests are located. These are home to iconic but threatened tree species like cedars (Cedrus libani) and cilician firs (Abies cilicica), to evergreen pines, cypresses, and a host of deciduous trees including oaks, chestnuts and pistachios.

In these coastal and mountainous regions, much greener than the rest of the country, deforestation is a major issue fueled by the ongoing civil war. This is particularly salient in the opposition-controlled parts of Aleppo and Idlib provinces, where millions of displaced people from around the country have sought refuge since 2014, fleeing the brutal repression of the Syrian regime. The opposition-held enclave of Idlib is now densely populated with around 3 million residents, 70% of whom are internally displaced from other parts of Syria. Many still live in tents in informal camps set up on agricultural lands that were haphazardly cleared to make space for these arrivals.

“Orchards were cut down to set up these camps, and forests were cleared to make space for crops,” recalls Ahmad al-Yousef, a 44 years-old environmental activist from Idlib who runs a weather forecast and monitoring page on Facebook. In Idlib and beyond, mass displacement and war also contributed to deforestation as people turned to forests to source firewood. Due to the widespread destruction of energy infrastructure during the war, electricity, fuel and gas became both scarce and very expensive.

But families cutting down trees to heat up in winter aren’t single-handedly responsible for the massive decline of forests. “Over time, organized groups began to form to cut wood and sell it, and after a while there were no trees left in the forest around Harem,” said Muhammad, the Harem resident. “Eventually, it reached the stage where people were even pulling roots from the ground, which led to this great disaster: there are no longer any trees or even roots left in this forest,” he adds.

Wood mafias

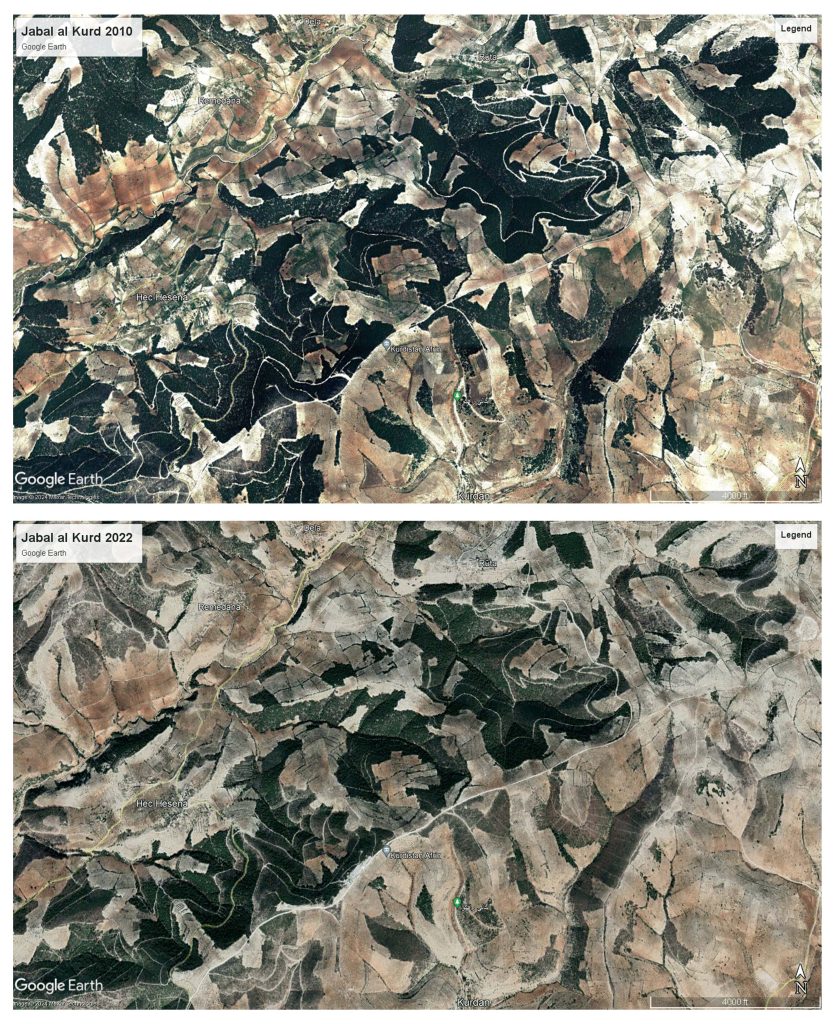

Over the years, unregulated logging became a tentacular business in certain parts of Syria, notably in the northern Aleppo province, which is under the control of Syrian opposition factions backed by Turkey. According to the same PAX report, this region recorded a spectacular decline of 60% of forested surfaces, which study authors largely attribute to organized logging run by armed groups, “a main driver” of deforestation since 2015.

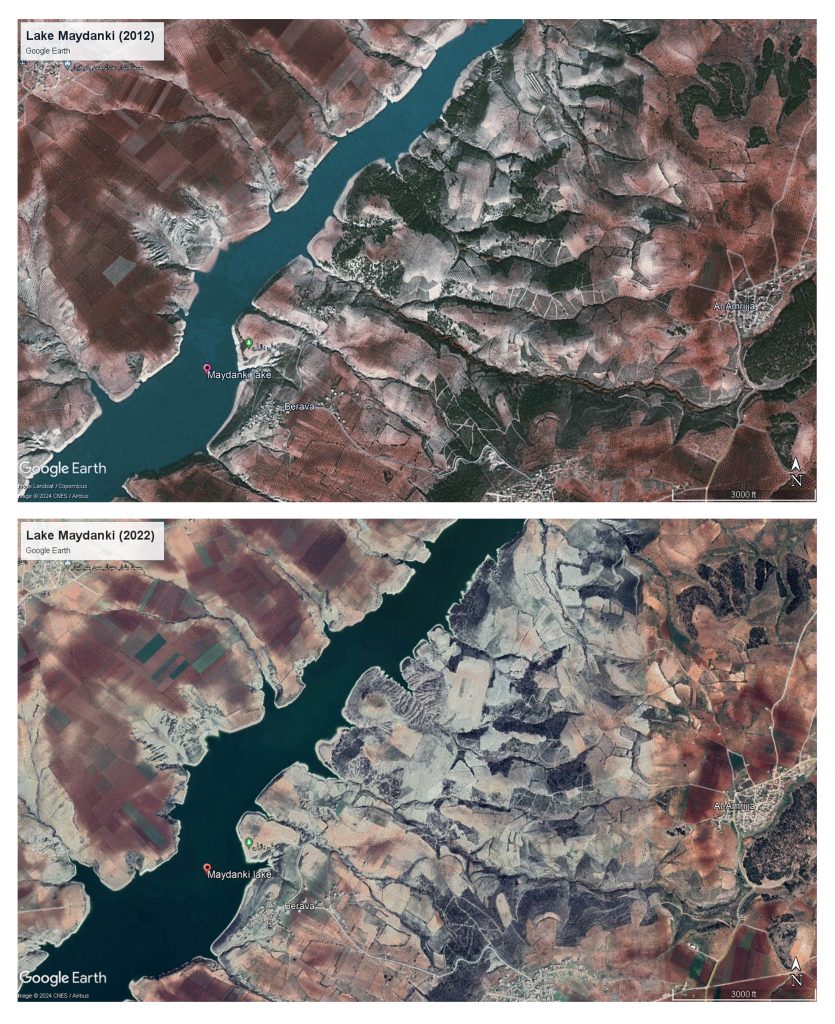

It’s not the first time that these military factions are accused of organizing and benefitting from widespread logging, which targets both natural forests and fruit and olive orchards. In August 2022, massive tree-clearing on the shores of Lake Maydanki, a nature reserve in the district of Afrin, sparked outrage and condemnation on social media, with several environmental activists accusing the Sultan al-Murad Brigade, a local armed group, of felling the trees.

While responsibility for this massive tree-logging is difficult to investigate, given that the area is tightly controlled by armed groups, many of these claims are corroborated by photos, videos and social media posts that show members of armed factions involved in the logging business. Several were verified independently by the Syrian human rights organization Syrians for Truth and Justice, who collected anonymous testimonies from members of the armed groups involved in the local business. The deep involvement of several opposition factions into wood mafias is also evident to many observers on the ground: one of the journalists we contacted for this story to photograph Idlib’s remaining forests even declined to participate in the project, saying the topic was “extremely sensitive” due to the heavy involvement of militias.

Those who lived in the region before the war say illegal logging has always been an issue – but on a much smaller scale than what Syria witnesses today. Local communities probably tapped discreetly into nearby forests for firewood, but the demand for it was dramatically lower, since there were abundant and affordable alternatives for heating, such as electricity and fuel. But in cases like Maydanki’s clearing spree, logging takes place in open daylight, using heavy machinery and affecting hundreds of trees over a short period of time.

Guilty fires

In addition to the damage caused by logging, violent wildfires blaze through swathes of Syria’s coastal forests practically every summer, contributing to the overall decline in tree cover.

The destruction they cause countrywide is difficult to assess precisely, since Syria is split into several areas of control and data is not centrally collected across these. In opposition-held Idlib and Aleppo, the Syrian Civil Defense – which handles firefighting – responded to roughly 175 fires across 74 towns and villages in 2023 alone, according to Ahmad Yazigi, one of its spokespersons. That same year, the fires affected a similar number of villages and ravaged 500 hectares in the government-held provinces of Latakia, Hama, Homs and Tartus. But the most extreme fire season to date was the summer and fall of 2020, when over 140,000 people living in mostly government-controlled parts of western Syria were displaced by fire.

Given the devastating impact they have, fighting these fires has become a priority in both government and opposition-controlled areas. In the wake of the 2020 fires, 24 suspected “arsonists” were sentenced by regime courts and subsequently executed. But these mass executions, which took place after speedy trials, were denounced by human rights activists, who say the regime used fires as a pretext to silence its opponents in the affected areas. Such drastic measures are also unlikely to have a significant impact, since the fires are caused by multiple overlapping factors.

Some are environmental, like “high summer temperatures and extreme heat waves that provide ideal conditions for a fire to start,” Yazigi, the Syrian Civil Defense spokesperson, tells UntoldMag. But human factors are usually the catalyst, particularly in opposition-held areas that are still regularly bombed by the Syrian regime and its Russian ally. “Aerial campaigns by regime forces and Russia sometimes spark fires, and the remnants of unexploded ordnance can also cause fires later on, when the munitions are exposed to high temperatures,” Yazigi adds.

Many fires are simply lit accidentally when people leave behind cigarette buds or shisha charcoal after a picnic in the forest, or when farmers trying to burn weeds in their orchards let the flames get out of hand. But some are lit intentionally. “In several cases that we responded to, the fires were lit by arsonists to collect wood charcoal, or to remove trees so that they could benefit from the land,” Yazigi says.

Tackling deforestation

Rampant deforestation affects all of Syria, directly or indirectly. When forests are razed to the ground, they stop performing many invisible – yet essential – services, like purifying the air, releasing moisture through their leaves, and storing carbon. Forest loss affects entire ecosystems, from the plants, lichen and moss living in their shade, to the animals living there and the communities that used to exploit their fruits and wood. When trees are removed, soil becomes increasingly exposed to the sun, affecting its quality and moisture. Tree roots also play an essential role in channeling moisture below ground and retaining soil in mountain areas, so erosion often increases in deforested areas, and water doesn’t find its way as easily into the ground.

“The various regions affected by deforestation are linked together, connected by mountains or riverbeds, and we are all directly affected – either immediately or in the long term- by the risk of losing our green areas,” Yazigi regrets. “Trees are an important wealth to preserve to protect future generations from environmental pollution and the diseases associated with it.”

But despite his organization’s efforts to fight forest loss by training local firefighters and raising awareness in local communities on wildfire prevention, much remains to be done to address the other root causes of deforestation.

On paper, things are moving forward in government-controlled coastal areas: under the new Forestry law adopted by the Syrian government in December 2023, private forest owners are not allowed to sell or rent their forested land once it’s been burned down, even partially. They must first replant at least 40% of the affected surface, under the supervision of a governmental forestry union, and ensure the trees survive for two years before they can apply for authorization from the Ministry of Agriculture to deal with their land freely again.

This rule probably aims at preventing people from intentionally setting fire to their forests to harvest charcoal, reclaim the land for agriculture or sell it to investors. It will also encourage private forest owners to invest in the regeneration of affected forests instead of converting the land to other uses. But like previous forestry laws in Syria, it is likely to be poorly or arbitrarily enforced.

For example, article 6 of the 2018 Forestry law (now replaced by the 2023 version) states that any public or private entity seeking to exploit a forest must obtain the Syrian government’ authorization, pledge to reforest the land once it’s been exploited, and submit a deposit to public authorities covering the cost of rehabilitating the area (in case the entity exploiting the forests fails to comply with its obligation to reforest the land). But several sources on the ground, including a worker in charcoal production and a former civil servant at the ministry of Agriculture, told the Syrian newsite Enab Baladi in 2020 that the law was hardly enforced and that the forestry police could easily be bribed.

The situation is hardly better in opposition-held areas, where “there are no plans to seriously support the planting or protection of forests,” according to al-Yousef, the environmental activist. “The most basic decisions that have been announced so far are not enforced. Trees are still being cut down daily, both in forests and in the areas where trees were re-planted.”

In Harem, Muhammad hopes to see the forests of his youth restored one day to their original beauty. “Reforesting this area would be a huge but very necessary undertaking,” he says. But this dream is a long way off, and he harbors no illusions. “It would need a lot of resources, active follow-up and a lot of specialists to supervise afforestation, care for the saplings and protect them.”