On 26 May 2004, almost exactly twenty years ago, the New York Times published a historical apology for its failures in covering the war in Iraq, including the events that lead to it, and its aftermath. As we know, that invasion caused the destruction of an entire country, and more than 300.000 victims.

The admission exposed the failure of a journalistic model. In fact, only a few months after the invasion, Brent Cunningham, the Columbia Journalism Review’s managing editor, wrote a piece with the title “Re-thinking Objectivity”. Objectivity, he said, often translates into journalists being “lazy”, as they can content themselves with reporting the two sides of the story, without investigating which one is closer to reality.

In the 1970s, after the Tet offensive of the Viet Cong, the US started to reconsider its involvement in the Vietnam war. Later, the coverage of the conflict was blamed for the shift in public sentiment against it. Even if reality was much more complex, the Vietnam war passed as proof that war reporters and photojournalists have indeed the power to change the course of a conflict.

We often hear these two conflicts mentioned in relation to the current war on Gaza.

The media failure in Iraq is recalled to draw a parallel with the recent failure to verify Israeli claims about 7th of October, such as the debunked story about the beheaded babies (the Gaza equivalent of the Iraq WMD).

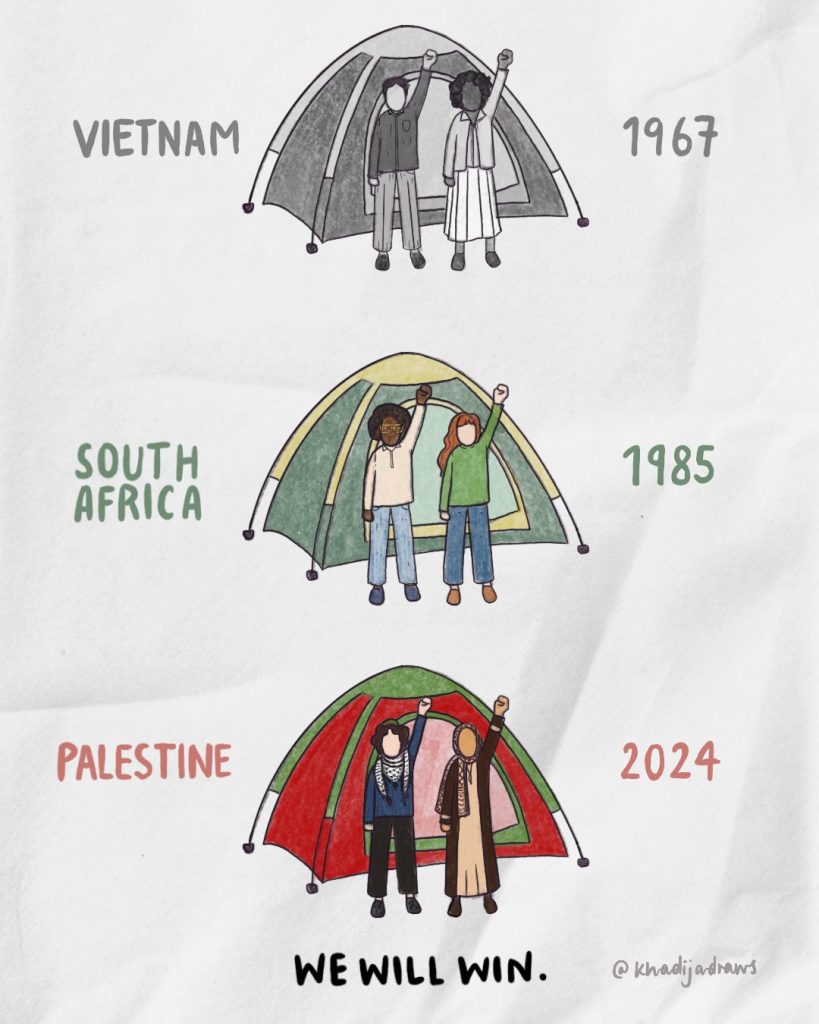

And it is difficult not to think about Vietnam in the face of the student encampments spreading across dozens of universities. This time, the parallel could be interpreted as a good omen: the protesters will win.

But, apart from some superficial similarities, using previous experiences as lenses to look at what is happening now is very misleading.

The events in Gaza are changing forever the relationship between media and politics in Western so-called democracies. In fact, we are witnessing a total disruption of the previous rules, and the complete failure of an entire system, while no viable alternative is in sight.

As the complete alignment of Western elites (politicians and journalists above all) to Israel is putting at risk the foundations of the liberal state, it is also destroying the credibility of its media systems and journalistic institutions.

And this time, a few belated apologies won’t be enough to go back to normal.

Expired objectivity

If the Iraq war gave a strong hit to some pillars of professional journalism, media behavior in Gaza is putting the final nails in its coffin.

Never before have mass media shown this level of disregard to verifying facts, when presented by only one side.

One exemplary case was the video at the Rantisi hospital: IDF spokesperson Daniel Hagari points at a paper on a wall with a hospital work shift calendar on it, and presents it as a ‘guarding list’ of ‘terrorists’, when in fact it contained no more than the days of week.

After the story was heavily debunked on social media, mainstream media, such as CNN, insisted on giving space to it, or, even worse, edited the content to exclude only the debunked parts, without any public acknowledgement of the previous mistake.

The rumor about babies beheaded on the 7th of October also managed to spread among different media outlets, including CNN, before some journalists finally began to cast some doubts over it.

Similarly, mass media were quite complacent in giving space to the Israeli constant statements to have found the command center of Hamas (always under hospitals), and the presence of tunnels was used, mostly unchallenged, as a justification to target civilian facilities.

The case of al Shifa hospital is, in this regard, instructive in how mass media can be manipulated by propaganda and reduced to rumor mills, as they accepted to circulate different videos of IDF soldiers traveling inside the facility and showcasing implausible evidence that the facility was the ‘Hamas Pentagon’.

Another example is yet again a front page story on The New York Times about alleged sexual violence perpetrated by Hamas militants on the 7th of October. While the content of the article started to be discredited, even in the paper’s own newsroom, the outlet refused to acknowledge its mistake yet.

The list could go on.

In this context, as Cunningham pointed out, objectivity becomes again an easy excuse for media organizations to give space to actors, and voices, who are clearly and repeatedly lying, without challenging them.

When it comes to Palestine, establishing false symmetries to cover the conflict is nothing new, and has quite a long history, but never to this degree.

All these cases prove that our news media, because of the way they function, are simply inadequate to confront political sources who are playing out the rulebook (i.e. they are ready to fabricate content and deny realities, as if their future credibility is no longer a valuable asset worth protecting).

It is quite ironic, however, that it was an Israeli official, Yair Lapid, a former prime minister, to put the objectivity to blame, saying that “if the international media is objective, it serves Hamas”.

Fairness, where art thou?

And yet the case of The New York Times about the 7th of October sexual violence actually proves Western media were far from being objective. Anat Schwarz, who was charged with collecting evidence on the ground, is an Israeli filmmaker and former air force intelligence official with no previous experience in reporting. She was later caught ‘liking’ a tweet inviting Israel to reduce Gaza to a slaughterhouse. As some journalists put it, selecting her to be a co-author of a front page story on a topic of that sensitivity and relevance was, at best, “poor editorial decision making”.

In early January, The Intercept published a study based on more than 1000 monitored articles from The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Los Angeles Times, and found a large disparity in how these media used emotive language selectively (for example avoiding using words like ‘children’ or ‘killed’, or ‘slaughter’ in the case of Gaza victims); emphasized Israeli victims over Palestinian ones; highlighted more anti-semitic acts than islamophobic ones, etc. An analysis by The Column of content distributed by US cable news gave similar results, that the title summarizes as ‘massacred’ vs ‘left to die’.

Therefore, it was not surprising that a memo leaked in April revealed that top editors of The New York Times demanded the staff not to use terms like ‘genocide’, ‘ethnic cleansing’ and ‘occupied territory’.

In fact, ‘double standards’ appear not to be an appropriate expression anymore, as we are rather witnessing a wide spread and multifaceted dehumanization of Palestinians, as Mohammed El Kurd, Karim Kattan (or, on this platform, Lamia Moghnieh and Nisrine Chaer), among many others, pointed out.

In light of the above, Christian Amanpour’s statement about the need for ‘international journalists in Gaza’, however moved by good intentions, appears not only unfair, once more, towards professional local journalists, but actually based on an idea that is crumbling in front of our eyes.

In general, for anyone who navigates both through social media and mainstream media, it becomes very clear that the latter made a big effort in hiding the extent of the horrors people in Gaza were going through on a daily basis. It is not about a single expression, or a single mistake.

It is rather the consequence of the editorial failure of an entire media system, based on the need to normalize the horror.

An era of the empire’s narcissism?

We cannot put all the blame on top editors and pundits alone. After all, we know that the media field comes only after politics. It is difficult for journalists to play a determinant role when political elites constitute a united front. Conversely, we learned that mass media can function as a counter power when there is, at least, some dissent among those circles (as it happened in Vietnam).

Today, political elites in many Western countries appear aligned as never before in supporting Israel’s war on Gaza (with some differences from country to country).

This alignment translates in an open denial of a massacre, and a pervasive repression of freedom of expression. Canceling events, firing, smearing, and marginalizing voices, arresting people, banning demonstrations, public and private threats, became increasingly common in the period following the 7th of October.

The demonization of counter hegemonic positions and the militarization of the public discourse (us vs them) intensified during the last few years, during the Covid 19 pandemic, and then the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but now has reached another level.

Therefore, the behavior of mainstream media can be understood only in this wider context of the weakening of democratic rules and practices.

All these elements (censorship, repression, news media incapable of challenging officials, the repeated lies, the dehumanization) are typical aspects of authoritarian regimes and belong to their ways of dealing with public discourse.

But since the fall into authoritarianism is far from being complete, and because many sincere ‘liberals’ are clearly not seeing it, I think we can look at this moment as a kind of collective narcissism that is seizing western elite circles who are increasingly aware of their decline, and at the same time are completely unequipped to face the challenges ahead (a multipolar world; growing inequalities; climate change; technological transformations).

It is a psycho-political drama that completely excludes the possibility to look at the Other and humanize it (both externally and internally).

One of the most brilliant definitions of this state of affairs was proposed by Naomi Klein. In a recent speech, she suggests that the total erasure of Gaza can be assimilated to a massive demonstration for everyone to grasp the new rules. A sort of equivalent of what the atomic bomb in Hiroshima meant for the postwar political order. Michael Hardt and Sandro Mezzadra used the expression ‘war regime’ as a new paradigm that can explain some of these trends.

It is not a Sci-fi dystopian novel by Octavia Butler: it is already happening. On 2 May, US senator Tom Cotton used the term ‘little Gazas’ to refer to the campus occupations by US students, labeled as “fanatics” and “freaks”.

It is only in this framework that we can understand the behavior of political circles and the media organizations following them. Only if we accept that this is about the creation of new rules, can we start answering questions such as: ‘Did they really think our societies could go back to normal, and pretend that nothing happened?’.

The answer, we now know is: there is no going back to normal.

So, who is winning the information war?

Indeed, the similarities, to anyone who lived in Syria, Egypt or other authoritarian regimes are quite striking, and one above all: social media, with all their flaws, have become the main space in which counter hegemonic narratives can be promoted and circulated.

It is in this context that a huge divide is emerging when it comes to the position towards the current genocide between the Global Majority on the one hand, and Western countries supporting the genocide – the Global Minority – on the other, but also within the societies in these very countries. In this last case, it also takes the form of a generational gap.

In the first case, it is very simple: Israel is definitely losing the information war, and risks to become (if it didn’t become already) a ‘pariah state’ in the international community.

The second case is more complex, as the polarization in these countries appears to be quite strong, and it is difficult to assess already all the consequences of Israel’s actions, especially in the long term.

However, it is clear that also in this case, even though a large part of the mainstream media and the political elites constitute a united front, the actors trying to counter their narratives managed to gain a considerable support that goes from endless statements of solidarity (including many film celebrities, prominent scholars, musicians, and renowned novelists), to millions of people demonstrating, to media activism, to occupations and a myriad of other initiatives.

If the movement against the war in Gaza was not able to significantly change the course of action it is because, as we have seen, of the strong consent among the political elites.

In terms of mobilized people, number of initiatives, sheer amount of media activism, and the impact on civil society, the movement that is trying to stop the carnage in Gaza is quite extraordinary. In both the US and Europe, a number of polls suggest that the amount of people demanding at least a cease-fire, and shifting towards pro-Palestinian positions, keeps growing. According to a recent poll among US citizens between 18 and 34 yrs, those rating Israel positively plummeted from 64% to 38%. In other words, almost half of young Americans radically changed their view during the last few months.

Is that a propaganda defeat for Israel and its allies?

Yes and no.

Yes, Israeli propaganda could have been better managed, and is another proof of Israel’s sense of total impunity. Hasbara, the Hebrew term for public diplomacy, during the last few months has become a term to mock clumsy efforts to sell a ridiculously fake story.

From the nurse video to the repeated efforts to show poor evidence of Hamas presence under hospitals, to ‘Pallywood’ (but the list is very long), propaganda content was sometimes so poorly produced that it could be identified as a fake even before more systematic debunking would take place.

To make things even worse for Israel, soldiers on the ground produced a sheer amount of visual documents of themselves committing war crimes, from prisoners kept naked and blind folded to mocking Palestinians in their destroyed houses, playing with the toys of the children who previously lived there, speaking about killing children, and so on.

But we would be very naive to think they lost the propaganda war. For different reasons.

First, the war on Gaza outmatches any similar conflict in recent history when it comes to civilian victims. The extent of the massacre is of such proportions, that even a very successful propaganda would not have been able to keep justifying the assassination of thousands of children for long, behind mantras such as ‘right to self defense’ and the horrors committed by Hamas on the 7th of October (some of which went under intense scrutiny later, including by Israeli media).

“In the battle of photos of pathos” admitted Moshe Klughaft, an Israeli strategic advisor, “we don’t stand a chance”.

Second, at least since the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the communication strategy of belligerents tends to be based on disturbing the narratives of their opponents, more than trying to control the media field. The key is not censorship as it used to be in most of the 20th century conflicts, but abundance. Creating doubts about what is really happening and repeating the same mantras enables the elites, when they are not divided, to gain time, and keep enough control in order not to change their actions.

In this context, the obsessive insistence on mantras that already lost most of their credibility among a large part of the public is clearly directed first of all to cliques of supporters who, at the moment, are also those who would be able to stop the war operation: the top officials in the US, UK, and Europe and the constituencies supporting them.

In this sense, even if the lies are plain to see, they deliver a specific message: this is the official line, and you know where you have to stand (similar to the propaganda mechanisms highlighted by Lisa Wedeen in Syria).

Third, because the main audience is Israeli. This explains, at least partially, the relative ease of politicians and journalists to express genocidal intent in public. It also explains the sheer amount of visual documentation of Israeli soldiers of their own crimes. It is true that there is nothing new in colonialist armies taking such photos, but it was later revealed that documenting active destruction and killings has been encouraged by an Israeli military department. The telegram channel 72 Virgins collected photos and videos inviting participants to share them as much as possible among the Israeli public, so that “everyone can see we are screwing them”.

The problem is not anymore to save the credibility of the media, and the messages, among a larger public, but only to keep a part of it quiet, and feed those already loyal.

Fourth, Israel adopted a diversified and quite effective strategy that combined activities aimed at muddying the waters through trolls or official statements; pressure on social media platforms; efforts to reduce original content from the Strip (preventing international journalists from entering; targeting Palestinian journalists and their families; and cutting power sources).

All these elements considered, we can say the information management was far from being perfect, but it was nonetheless partially effective in attaining one main objective: gaining time and containing the reaction to a genocide happening under the eyes of the entire world.

In other words, given the amount of destruction and killing, the consequences in terms of image for Israel and its allies could (and should) be much worse.

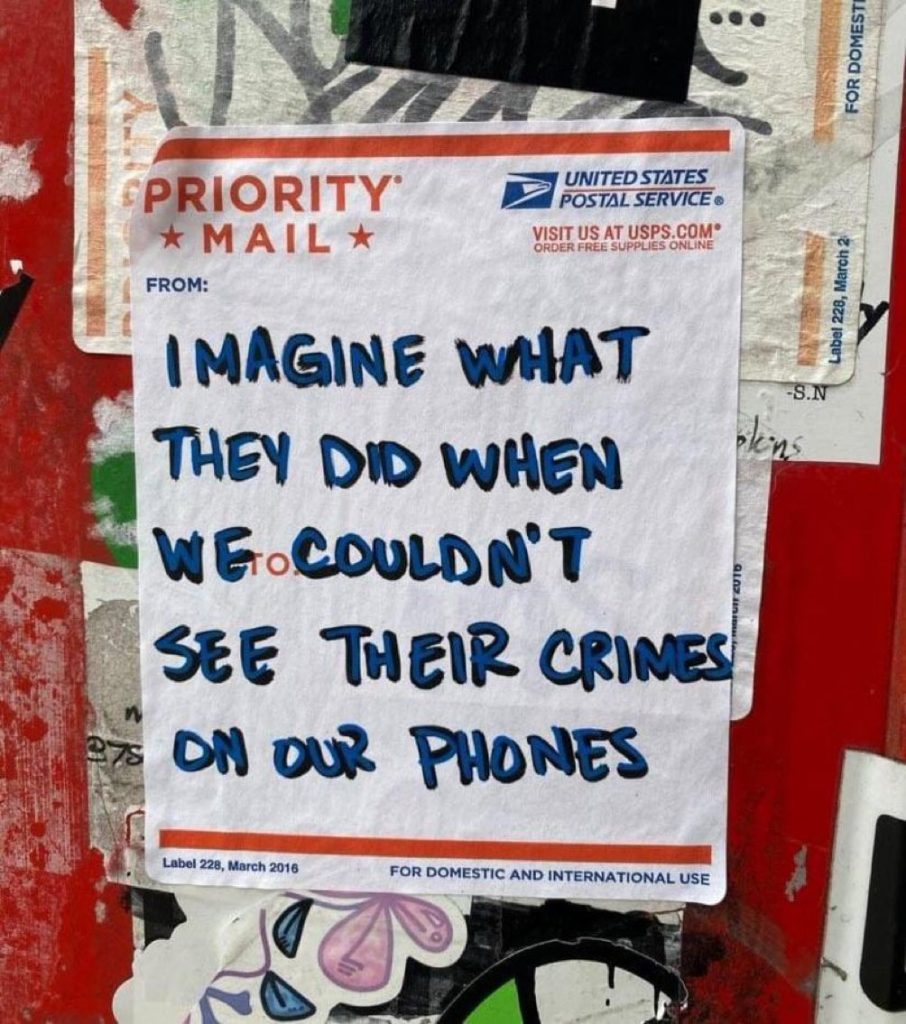

At the same time, there was an element that constituted, and still constitutes, the only real obstacle capable of derailing those propaganda efforts: a connected young generation living the genocide unfiltered on their smart phones.

Towards separated information worlds?

On 3 December 2023, Jonathan Greenblatt, the CEO of the Anti Defamation League, said: “We have to talk about Tik Tok. It is the 24/7 channel of so many of our young people and it is like Al Jazeera on steroids, amplifying and intensifying antisemitism and anti-zionism and with no repercussions.”

This followed a leaked audio that started to circulate in November, in which Greenblatt states that: “We have a Tik Tok problem” and “a major generational problem”.

Given the frequency of similar statements, the decision by US President Biden to sign the so-called “Tik Tok Ban”, on 2 May was not surprising. A few days later, Israel banned Al Jazeera, further confirming the authoritarian trend of so-called liberal ‘democracies’.

Is Tik Tok really an obstacle for the political elites in the West at this moment?

Of course it is. Social media always tends to create echo-chambers, but in this case, because of the relentless effort to normalize the genocide on mainstream screens, it seems like Tik Tok (and to a lesser degree other platforms) have shaped a completely different experience for their users.

Sim Kern, a queer, Jewish writer, very popular on both Tik Tok and Instagram, in a video published on 1 May 2024, describes a conversation she had about the student encampments with an older, ‘liberal’, person, who was active in the protests at the time of the Vietnam war. What she says highlights quite well the phenomenon:

“What this moment has that the 1970s did not is cell phones and social media. I said ‘you were activated as you were because Walter Kronkite came on the news every night and announced how many people have died. The youth today are activated because they have seen with their eyeballs in HD on their phone not once a day, but all day long, they’ve seen the people dying. They’ve seen kids being pulled from rubble. They’ve seen parents crying over the dead bodies of their children. We’ve seen horrors’. (…). He is not gonna get Instagram and start following Bisan and getting the updates. We have to transmit that. So I just told him about Reem, and Sidra, and Hind, and all the horrifying things that we’ve seen and how it’s affected me. And he listened and he got it. (…). He did not know. He just fully did not have any idea what was going on in Gaza and what the youth of today have been watching on their cell phones and why they are camping out. And once it was explained to him, he got it. (…). We are living in totally two different informational worlds. If they are not on Tik Tok and Instagram and watching the reels, they’d have no idea what’s going on”

In a similar way, Simone Zimmerman, a Jewish woman activist and founder of If not Now states in another interview:

“The reason why there are so many young Jews fighting for Palestinian freedom is because we read the news. We see the horrors that are being committed against Palestinians. (…). I think it is just undeniable the experience of being a young person on social media right now. You almost have to work quite hard to not know what is going on in Gaza right now. Because the genocide is livestreamed on to our phones. We are seeing young people who look like us, have the same hopes and aspirations as we do, who want a normal life, to be safe and free. These amazing storytellers and content creators…I am thinking of Bisan for example, who is making these beautiful storytelling videos, but they come from tents of displaced people, reporting on the horrific destruction happening all around them every single day. (…). You can’t unsee those things. (…). Many of our parents do not see the horrors that we are watching on our phones every day. They do not see injured children shaking on hospital beds. They are not seeing young people trying to get food for their families. And they are not seeing the videos of young Israeli soldiers who are celebrating their war crimes, laughing and playing on the rubble of Palestinian homes. Both of those experiences feel like it is reality unfiltered, and it is so radicalizing to see all what is happening on our phones. I think many people are really transformed by that”.

Of course this online experience, and the way it is activating especially young people, didn’t happen in a vacuum. As we noted already in relation to the 2021 events, Palestinians developed during the last years much more capacity to promote their narratives, even in mainstream media, thanks to a new generation of voices, but also by creating a connection with other struggles such as Black Lives Matter, Global South democracy movements, and anti-colonial movements.

Moreover, the enhanced availability of smartphones and digital cameras in Gaza helped to provide a constant and enormous flux of images in real time during the last few years.

When Israel started to kill civilians indiscriminately, many Palestinian video makers in Gaza had already hundreds of thousands of followers.

What happened next was a result of the algorithm of Tik Tok, which helped to make the content produced by them immediately viral, and the storytelling ability (and the courage) of people like Bisan Wisam, Motaz Aziza, Plestia Alaqad, Hind Khoudari, Aboud Batah, Ahmed Hijazi, Saleh Jarafawi, Wael Dahdouh, Yara Eid, and many others.

In a few months, most of these content producers managed to conquer the hearts of millions of followers and, as we saw, to connect with and mobilize many of them.

A blurred photography of the future: A Cadmean victory

So what about the future of journalism and media?

We are waking up in an upside down media world. A reality in which Tik Tokers debunk content that professional media with a prestigious history did not care to verify, and young activists elaborate and present complex and fact based arguments while old star journalists stutter emotionally and frantically mantras such as ‘right to self defense’, ‘do you condemn Hamas?’.

A world in which an entire generation is understanding local journalists in Gaza have more credibility than officials repeating desperate invocations of concepts such as ‘free world’, ‘democracy’, and ‘human rights’ that appear increasingly emptied of their meaning.

This could seem at first sight like a positive outcome, as it contributes, today, to defeating a callous propaganda trying to justify an ongoing genocide and to promote, as we have seen, a quite dark vision of our future.

Winning this battle is indeed the priority. We cannot afford to live in a world that justified or even supported a massacre live streamed in front of our eyes. Any other outcome would be a disaster.

However, the cost of this ‘victory’ (if we may use this word) can be very high, and while the responsibility falls, almost exclusively, on Western political and media elites, it will be all of us who will pay the price.

We still need journalists and media organizations capable of contextualizing, verifying, and filtering content.

While mainstream media are sacrificing their credibility to defend the (alleged) interests of certain political projects and the people behind them, social media like Tik Tok are not an alternative. The algorithm and the virtual architecture of Tik Tok helped, in the case of Gaza, to counter a certain type of propaganda, but in other cases can be less effective (lack of appropriate visual material) or counter productive (can be used to spread misinformation and hate speech).

As for other current blockbuster platforms such as Instagram and Facebook, we already know they are not a neutral space, as they tried to contain pro-Palestinian narratives as much as they could, by shadowbanning, over-moderating and censoring content; and other times closing accounts (including some of the content producers in Gaza). Others, such as X, formerly known as Twitter, or Telegram, have become spaces where hate and divisive speech can thrive. Yes, this time we used them to counter hegemonic, genocidal narratives, but they could just as easily be turned against us.

Another element is that this war saw also a significant use of Artificial Intelligence in relation to war tactics but also media content production. This should be another cause for preoccupation in the next few years, as it will probably further advantage the actors provided with more resources, making current imbalances even worse.

Finally, a last, and perhaps most important, reason for not being particularly optimistic is that the propaganda strategies employed by Israel and its supporters were not so ineffective. If they are partially failing, it is only because thousands of people are being exterminated. These actors adopted a series of measures that are part of the modern propaganda toolkit (aimed mainly at creating disturbances and disruptions in the media discourse of their enemies) in addition to forms that are more typical of authoritarian states (extensive use of misinformation; assassination of local journalists; no access for international journalists; dehumanization of the enemy, etc.).

The implementation of the last ones have a detrimental effect on the credibility of mass media and political sources, but they are quite effective in creating an information chaos that can prevent many people from positioning themselves. This is the most important goal for whoever is committing war crimes.

This degeneration of propaganda strategies is no good news as it paves the way to a world where it is more acceptable to lie in the face of cameras, and the credibility of the media will be close to zero. In this context, it is not Tik Tok that can save us.