If there is a founding myth of the Spanish nation, it is to be found in Asturias, a region on the Cantabrian coast in northern Spain between Galicia and the Basque Country. Legend, not so much history, has it that Don Pelayo, the Asturian king, resisted the Arab invasions and, with the help of the Virgin of Covadonga, patron saint of Asturias, defeated the Muslim army around 722 and thus began the ‘Reconquest’.

For nationalist pride, Asturias is the ‘cradle of Spain’, a land of old Christians never trodden by the Muslim invaders. Perhaps that is why most Asturians, and visitors too, are unaware that in the West of the region, a few kilometers from the town of Luarca and at the foot of the Camino de Santiago, stands a Muslim cemetery with Arab tiles and a horseshoe arch. With no information sign to help visitors get over their astonishment, this Moorish cemetery in Barcia in a semi-ruinous state, appears in the middle of a forest and just a few meters from the coast.

Bernardo Álvarez-Villar

There are more unknowns than certainties about this necropolis. It is not even known how many people are buried there but it is estimated to be between 100 and 300 Rifian Muslims from Melilla and other areas of the former Spanish protectorate in Morocco. They were part of the Grupos de Regulares de Melilla, a unit of indigenous troops founded in 1911 and recruited by Fransisco Franco’s army to fight in the Spanish civil war (1936-9).

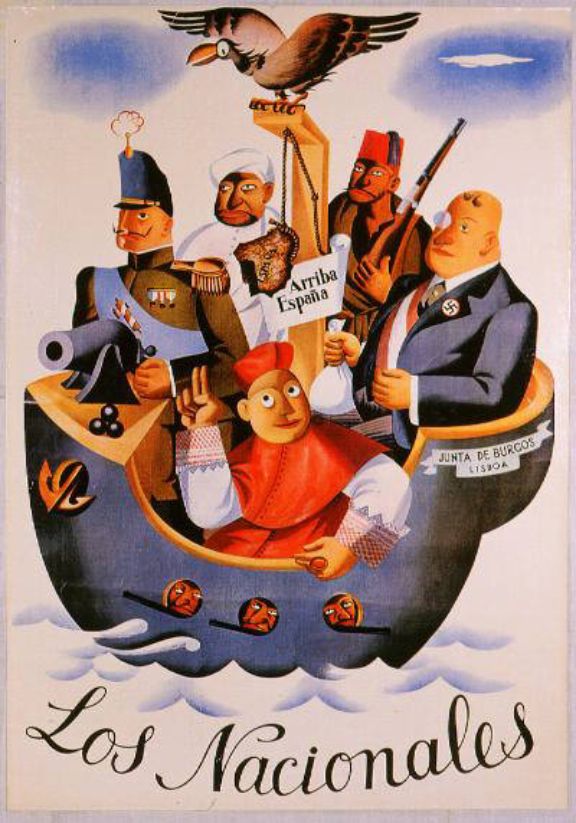

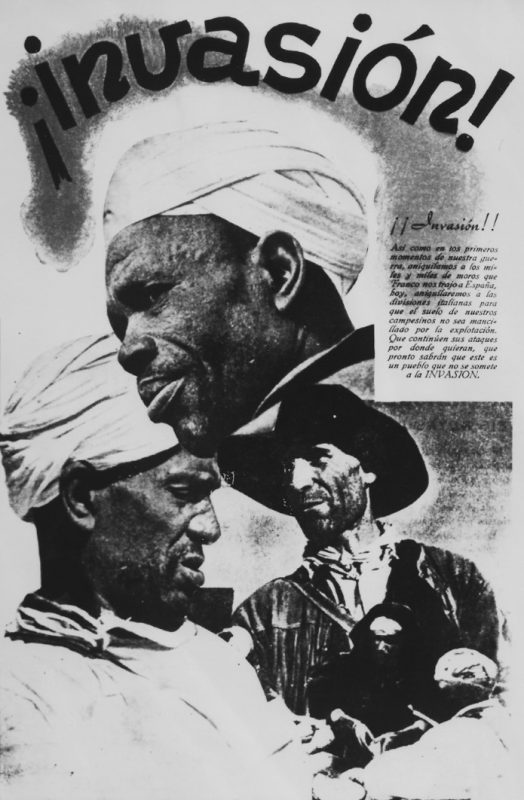

“One of the great icons of Republican war propaganda was that of the invading Moor, which would be a kind of return of the invaders of 711,” explains Xosé Manuel Núñez Seixas, a historian and author of “Sites of the Dictators. Memories of Authoritarian Europe, 1945–2020”.

Francesc Tur who wrote the book “The Invisible War. Moors, African Americans and Gypsies in the Civil War” agrees: “In the Republican press there was a great demonisation of the Arab, who was treated as if he were a savage, a beast who came to rape Spanish women.”

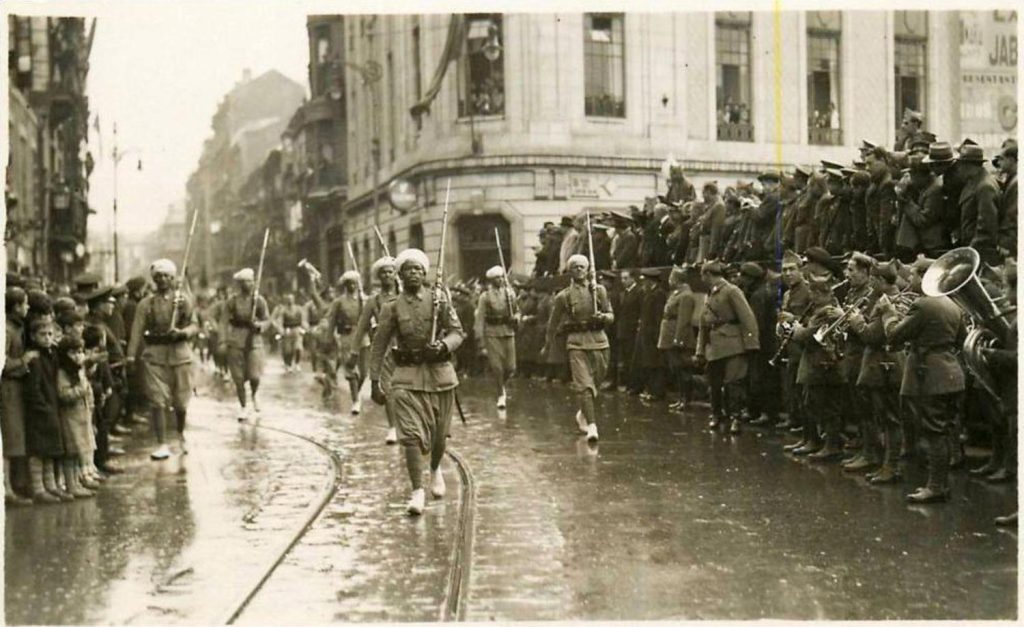

In October 1936, at the beginning of the war, several units of Moroccan soldiers from Ceuta, Melilla, Tetuan and Larache landed in Galicia. Franco’s coup d’état had triumphed in Galicia, but not in Asturias, a region with a working-class and leftist tradition. In fact, many of the soldiers who organized the 1936 coup d’état that brought Franco to power were part of the so-called “Africanists”, Spanish soldiers with experience in combat and repression in the Spanish colonies in Morocco.

Two years earlier, Asturian miners had staged the October 1934 revolution, creating an ephemeral Asturian Socialist Republic that was harshly repressed by the Republican army in a matter of weeks. It is estimated that 2,000 people were killed by Africanist soldiers and regular Moorish troops, according to historians such as Gabriel Jackson or Julian Casanova, although other historians give higher figures.

The cruelty of these soldiers caused such terror among the Asturian population that a stereotype about the malignity of the Moors began to incubate, opportunely used as a weapon of psychological warfare by the Francoist side, and fed by centuries of legends and popular songs related to the battle of Covadonga.

Aurelio del Llano, one of the best known Asturian folklorists, heard in 1920 a shepherdess reciting the ‘Romance de la cristiana cautiva’: “Caballero yo no soy mora,/ soy cristiana cautiva, me cautivaron los moros/ siendo niña chiquitita” ( Gentleman, I am not a Moor, I am a Christian captive, I was taken captive by the Moors when I was a little girl). In the last days of the revolution of 1934 revolutionary socialist leader Belarmino Tomás wrote about the Moroccan military saying that “their behavior is not worthy of any civilized nation.”

This was the reason why the military coup plotters chose these troops to march from Galicia to Oviedo, the Asturian capital where Coronel Antonio Aranda, leader of the coup d’état in the region, was holding out in a city besieged by the Republicans. During the advance towards Oviedo, the town of Luarca – some 90 km to the West – became the nerve center of the national rearguard, and home to the military government of the area. The bloodiest battles took place on the slopes of Mount Naranco, in the outskirts of Oviedo, where the Moorish soldiers died by the hundreds. “Being an elite corps and serving in the vanguard,” explains José Manuel Rena, a resident of Barcia and retired history teacher, “they were in the front lines, and there was real carnage.’’

Indigenous troops, cannon fodder

The main reason these Moroccan soldiers enlisted to participate in a foreign war was the pay they received, “about four pesetas a day, a good wage for ordinary people,” as Stanley G. Payne has written in ‘40 fundamental questions about the Spanish civil war’. There were also benefits for their families in case they died in combat.

Beyond economic reasons, Payne also argues that some of these austere Rifian shepherds and peasants had been convinced by Franco’s nationalist, Catholic and reactionary ideology that the war being waged in Spain was against atheists and enemies of religion. According to him, these young Moroccans were attracted to “appeals that emphasized the almost jihadist values underlying the fight against ‘red atheism’ and ‘godlessness’, so the volunteers were left in no doubt that they were fighting truly evil people.”

Consistent with this shared religious faith, the Muslim soldiers integrated into Franco’s army were provided with personnel and infrastructure to meet their needs. A theater was set up in Luarca as barracks for the Moroccan troops, who were always accompanied by imams and faqihs, experts on Muslim law who were in charge of burials according to the Islamic rite. And it is believed that it was precisely one of these faqihs who directed the construction of the Barcia cemetery in the autumn of 1936, using both voluntary and forced local labor.

It is a striking ideological role reversal: while the Republican, enlightened and cosmopolitan left spread a brutal and savage image of the Moors, the philo-fascist right resorted in its propaganda to the Moor “as a symbol that was part of the image of Franco as an Africanist warlord,” as Pablo León Gasalla, Director General of Culture and Heritage of the Principality of Asturias, explains, intellectuals and propagandists on Franco’s side celebrated the unity of the Spanish and Moroccan people in their struggle in defense of traditional civilisation. However, behind the rhetoric, the reality was quite different. “Moroccan soldiers were used as cannon fodder on the front line,” León Gasalla explains.

Ruin and abandonment

The Moorish cemetery of Barcia, the only vestige of Islamic architecture in Asturias, occupies a total area of 4,500 m² in two distinct parts. On the one hand, the burial area, rectangular in shape and with guard towers at its four corners, is accessed by passing under the horseshoe arch, once covered by a wooden door more than two meters high. In front of it, a mosque began to be built, intended for washing and wrapping the corpses according to the Muslim rite, but it was never completed.

“There was an imam called Omar,” recalls Rena, a resident of the village of Barcia, “who, after the war was over, came every year to clean and look after the cemetery. He died around 1970 and never came back.” Since then the undergrowth has grown until the graves are indistinguishable. Sections of the wall have fallen down and the watchtowers are full of rubbish.

“The first time I went, I was 13 or so, around 1979,” recalls historian Núñez Seixas, “it had a certain air of mystery about it. Then I went back as an adult, with my wife, and it was a mess. It’s a half-clandestine place.”

Bernardo Álvarez-Villar.

The village of Barcia, a municipality of 579 inhabitants, is the entity that owns and is responsible for the cemetery. Ricardo García Parrondo was its president between 2007 and 2023, he recalls: “When I joined, we cleaned it up, because it was an absolute scrubland. We tried to keep it that way. We would have liked to clean up the place more, but we have a very low budget and we can’t afford it, because it’s a complicated job. We’ve been trying for years and knocking on the doors of all the official bodies.”

Ismael González, councilor for tourism in the Valdés town council, where the necropolis of Barcia is located, does not hide the fact that this space “is not among the priorities for action in terms of either heritage rehabilitation or tourist use,” and that therefore a municipal intervention to rescue the cemetery from the ruin to which it seems doomed is ruled out. The cemetery has been part of the Cultural Heritage Inventory of Asturias since 2012, which opens the door to receiving grants for its rehabilitation.

However, according to León Gasalla, the region’s director of heritage, “no aid has been requested,” which is indicative of the lack of interest in a space that does not fit into the usual categories of historical memory in Spain. It is not very clear what consideration this cemetery would have in the recently approved Law of Democratic Memory, which contemplates the removal or elimination of those “buildings, constructions, shields, insignias, plaques and any other elements or objects attached to public buildings or located on public roads in which commemorative mentions are made in exaltation, personal or collective, of the military uprising and the Dictatorship.”

Bernardo Álvarez-Villar

In recent months there has been a heated public debate in Spain over the “Pyramid of the Italians”, a funerary shrine housing the bodies of Italian soldiers sent by Mussolini to fight in the Spanish civil war. The autonomous government of Castilla y León, presided over by the liberal-conservative Popular Party in coalition with the far-right Vox, has just ordered the protection of the monument in order to avoid what they consider a “rewriting of history” resulting from the approval of the aforementioned law. Both the Moorish cemetery of Barcia and the Pyramid of the Italians were built to bury fallen soldiers fighting on the side of the coup, but there is a fundamental difference between the two: the former is a simple cemetery, and the latter was conceived as a shrine exalting fascist ideology.

So far there has only been one attempt to restore the cemetery. It was an initiative of the autonomous city of Melilla on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Cuerpo de Regulares, the unit of indigenous troops based in Melilla. García Parrondo says that he had conversations with the councilor of Melilla, and that in 2011 a plan was drawn up, budgeted at EUR 200,000, for its comprehensive rehabilitation. But those were the years of the economic crisis, and the project was discarded due to its high cost.

Bernardo Álvarez-Villar.

This disdain for the Moorish cemetery of Barcia is not exclusive to the administrations. “A small sign was put up and covered with graffiti,” recalls García Parrondo, “because there are people who understand that those who are there fought against their families, and we have to go against them no matter what.”

Núñez Seixas, on the other hand, finds a curious contrast with other cemeteries of soldiers allied to Franco’s side, such as the Italian military tabernacle in Zaragoza. “I would add that Morocco’s lack of interest, and probably lack of means, is also clear: it would be remembering the fighters for the colonizer, after all,” he explains.

Nobody remembers the Moorish soldiers

The Barcia cemetery occupies an elusive place that is difficult to classify in the collective memory. “The problem with the Moors of the civil war,” García Parrondo thinks, “is that the winning side did not treat them well, and the losing side never wanted them. When the war ended, they were left in limbo.”

Núñez Seixas agrees that it is an “unwanted and rather uncomfortable memory. There is a double rejection, as the winning side recognises that there were mercenary and non-Christian troops in their ranks, and the memorialist movement is shocked to preserve the space as a burial place for another confession.”

León Gasalla also believes that this is “a very painful part of the past, which is conflictive and controversial.” But one way of dealing with it would be to maintain the cemetery and try to contextualize and explain why it is there. “Issues that have to do with the dead are delicate,” adds Núñez Seixas, “and in western Asturias there were quite a few executions. The memory of the Moors is very negative in the popular memory of Asturias because of their role in the repression but, on the other hand, they were mostly people recruited half by force. They could be seen partly as victims. So, what recognition should we give them?”

For García Parrondo, the ideal would be to recover the place as “a place of historical memory, to remind young people of what happened. And for it not to happen again.”

Nuñez Seixas agrees that “it should be possible for the authorities to re-signify it intelligently, without claiming the participation of Moroccan troops in the war, but rather explaining it. They are probably afraid of controversy, but it could be an interesting place for cultural tourism. It would have to be tidied up, redefined and investigated. And, if someone wants to perform a funerary cult, it should be possible.”

For years, the Muslim community in Asturias, made up of around 9000 people, has been asking to be able to use the necropolis, offering to take charge of the rehabilitation and maintenance of the space. They are asking to use it as a burial place for Muslims from Asturias, Galicia, Cantabria and León. “In the whole of Asturias we have only one plot in the Oviedo cemetery, and it is almost full,” says Yahya Zanabili, a retired Syrian doctor who came to Spain in 1970 and is the delegate of the Islamic Commission in Asturias. “Besides, the graves are not all oriented towards Mecca. As Spanish citizens we have the right to be buried according to our religious beliefs, and in Asturias this is not guaranteed.” The Muslim cemetery in Seville, also built during the civil war, was later rehabilitated and handed over to the Muslim community as a burial place.

In recent decades, the use of the Barcia cemetery has been very different. According to Rena, the resident of Barcia, there were neighbors who took the stones from the unfinished mosque to use them as foundations for their own houses. While we were visiting the cemetery, a neighbor who was passing by told us that a section of the wall was pulled down so that carts loaded with firewood from the pine trees planted inside the enclosure could be taken out. Rena sums it up in one word: “A pillage.”