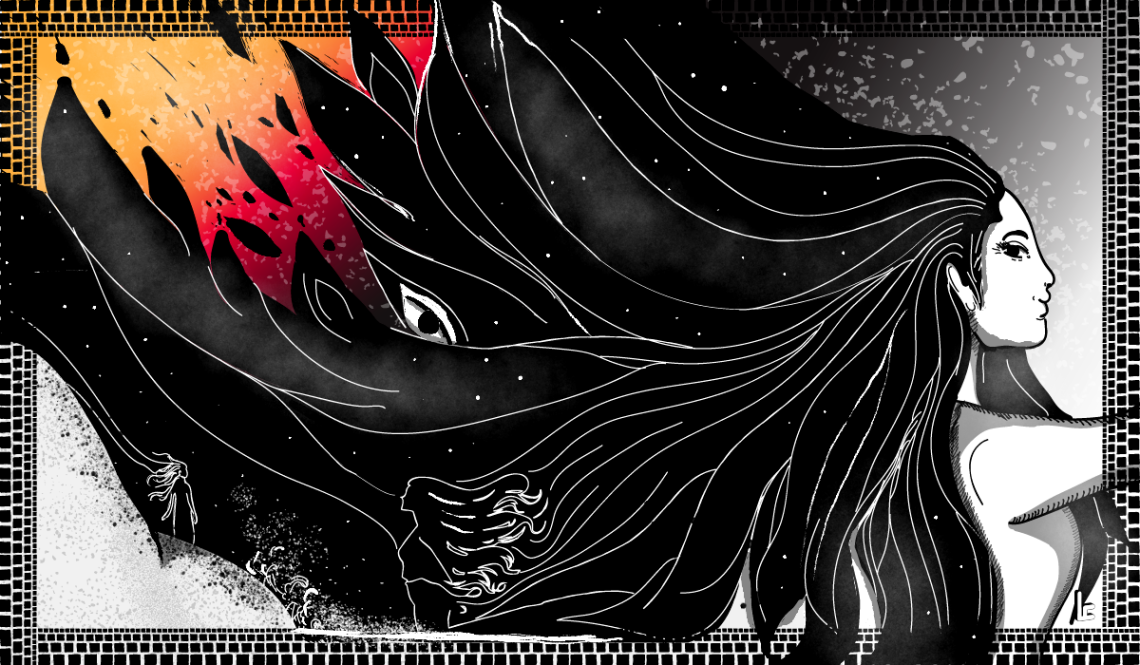

Growing up in Morocco during the 1990s, I sometimes went to sleep under the threat of Aicha Qandisha’s invocation. Often portrayed as half-woman, half-camel, this figure from Moroccan folklore associated with lust and possession, sometimes depicted as an ogress, sorceress or avenger, is one of the most fascinating creatures in the kingdom’s oral tradition. I used to imagine her dressed in white, with camel hooves and long, cascading black hair. I didn’t know much about her, just that she was to be feared. When I inquire about what she evokes in people, the responses are always the same: vague, disinterested and marked with superstition.

Today, with my political and feminist awareness, I believe that Qandisha, like many powerful women in history, was demonized to be erased from memory. I choose to believe in her existence, envisioning her in her most glorious form. Exploring her figure and legacy represents my effort toward repair, redemption, and reconciliation.

The archetype of the witch: between fascination and demonization

Despite having nearly 20 names based on her attributes and regional variations, Aicha primarily means ‘the living one.’ The origin of Qandisha, as enigmatic as her existence, could stem from Portuguese, referring to her status as a fallen countess (condessa in Portuguese), from Hebrew qadesha meaning sacred prostitute, or from Astarte, the ancient Canaanite mother goddess.

The founding myth of Qandisha suggests that she was a significant figure in the anti-colonial resistance against Portuguese occupation in the 16th century. While she is scarcely present in contemporary popular culture and artistic productions, Aicha Qandisha’s story continues to be transmitted, though often in a partial and incomplete manner.

In Ahmed Maanouni’s 1981 documentary film Transes, Larbi Batma, leader of the renowned group Nass El Ghiwane, completely refutes the thesis of the jenniya—witch—referring to her as one of the “first rebels in history.” He recounts the massacre in her village near Jorf El Asfar in the province of El Jadida and the rape she allegedly suffered at the hands of a soldier of the occupation.

This experience supposedly inspired her revenge: her enchanting beauty would become her weapon of war, seducing the colonizers, luring them into the woods, and killing them. In this sequence, archival footage in cutaway shots notably shows Bousbir, the prostitution ghetto of the protectorate in Casablanca, and other testimonies of the brutality of the French armed presence.

This reflects a clear stance on colonial history and the associated sexual violence—still too sugarcoated —by the director, whose film was restored by Martin Scorsese in 2007. Maanouni speaks of intersectionality ahead of its time, highlighting the exploitation of bodies and the dispossession of land, as well as the interdependence of feminism and decolonization. Aicha Qandisha thus suffered a double penalty: being a woman and being indigenous, objectified and hypersexualized by patriarchy and occupation.

Numerous variants of this legend exist where Qandisha is alternately a fille de joie, a notable’s daughter, an Andalusian princess, or a Portuguese countess. A controversial character, between the Judeo-Christian succubus and a mermaid, she would use her charms and overflowing sexuality for sinister purposes. With her pale skin, almond-shaped black eyes, and blood-red mouth, she would seduce men to oblivion until they lose their minds.

Vengeful, misandrist, and insatiable, she would particularly target young men—those she loved or those who did not fulfill their roles as family heads or providers. Some beliefs also consider her the daughter of Sidi Shamharush, sultan of the djinns, regarded as a saint by tribes of the Atlas. Present in the Sufi Buffis order, this version of Aisha jenniya suggests she is capable of possessing people or changing her appearance.

Whether the massacre of her family by the Portuguese troops was an act of reprisal or the starting point of her resistance is irrelevant: all stories end in a bloodbath and plunge our anti-heroine into madness. Upon her death, she is said to have become a weeping spirit, a llorona, haunting the forest and continuing to hunt men to devour them.

Furthermore, the Portuguese occupation of Morocco coincided with the peak of witch hunts in Europe and the United States. In the context of what is referred to as “the first femicide in history,” which is also the title of a documentary by Dominique Eloudy-Lenys released in 2024, it is plausible that the Portuguese invented the legend of the evil ogress, possibly drawing on other traditions, to destabilize her and dissuade people from rallying with her—or even to hunt her down.

This legend includes certain characteristics found in Western descriptions of witches: like Maryse Condé’s Tituba, a victim of the Salem witch trials, she would have lived in isolation, near a watercourse, river, or the sea. As a solitary, powerful, and desirable woman, she was seen as a clear danger that needed to be neutralized.

However, in Gnawa trance ceremonies, or hadra, she is still invoked as Lalla Aicha, honoring her as a holy figure to communicate with spirits. The ambivalence of her character endures, between spells and healing, possession and exorcism, creating a complex relationship of both fear and veneration.

The great forgotten women of history

In the end, very little is known about Aicha Qandisha, and there are no historical sources or written records to define this polymorphic myth. Given that history has predominantly been written from a male perspective, it is clear that many women have been erased from it, and folklore often serves as a simple and effective means to discredit the powerful.

The earliest known text written and claimed by an author though —the first instance of I—is by a female author, the Mesopotamian princess Enheduanna, who in 2,300 BCE addressed a letter to a goddess. This example, highlighted in Titiou Lecoq’s book Les grandes oubliées: Pourquoi l’Histoire a effacé les femmes, is part of her effort to trace the erasure of women and their contributions throughout history.

Lecoq’s research suggests that the origins of violence and inequality can be traced back to the Neolithic era with the advent of sedentarization, private property, and agriculture, which reshaped the understanding of fertility. Women thus lost their status as embodiments of the mother goddess and the miracle of life, becoming mere receptacles for seeds. Lecoq’s goal is to shift perspectives, reclaim history, and document the trajectories of remarkable women.

In Morocco, the existence of many significant figures remains debated today, such as Fatima Al-Fihriya, who founded Al Qarawiyine in Fez, the oldest continuously operating university in the world.

The story of Haddah Zaidia, better known as Cheikha Kharboucha, also remains a mystery. A popular singer regarded as the mother of aita (“the cry” in Moroccan dialect)—a rural musical genre linked to tribal and anti-colonial struggles—legend has it that she was walled up alive by a bloodthirsty caid who was secretly in love with her, outraged by her bold, politically engaged lyrics. While her music endures, her life remains elusive. Surrealist poet André Breton described her as “a ribbon around a bomb.”

Dihya, a formidable Amazigh warrior of the 7th century, was demonized by her Arab enemies, who called her La Kahina, meaning priestess or prophetess, suggesting that her military prowess was the work of the devil.

While the destinies of other Moroccan women with extraordinary journeys are better documented and less distorted than Qandisha’s, they remain marginalized. Aside from a few rare biopics—such as those about Zineb Nafzaouia, the 11th-century founder of Marrakech and wife of Almoravid Sultan Youssef Ibn Tachfine, and Fatima Mernissi, a prominent sociologist and Moroccan feminist leader, both of which were incidentally directed by men—female historical figures are seldom recognized in collective consciousness and popular culture.

There is no Malika El Fassi Avenue, named after the signatory of the independence declaration who secured women’s right to vote, nor an Avenue Sayyida Al Hurra, despite her being a pirate queen allied with Barbarossa.

Symbolism matters greatly. While some still claim that feminism is a Western import designed to corrupt the virtue of Muslim women, it is clear that Moroccan women have always played a significant role in history and fought for their rights and freedom. Therefore the issue of representation remains more relevant than ever.

Towards a collective rehabilitation?

It wasn’t until the 1970s in the United States that the archetype of the witch was reimagined as a feminist icon. In 2001, the Massachusetts Assembly passed a law clearing the names of all those condemned during the Salem witch trials. Since then, a wave of official rehabilitations has continued across Europe, supported by activist movements.

This process of reparation is complemented by efforts to remember, including the erection of monuments and other commemorative tools. In 2016, Pope Francis elevated Mary Magdalene, previously regarded by the Church as a prostitute, to the status of “apostle of the apostles” by dedicating a liturgical feast in her honor.

Two years later, Garth Davis’ film Mary Magdalene portrayed a character – played by Rooney Mara – imbued with gentleness, wisdom and humanity, while demonstrating a form of independence and rejection of the patriarchal model and motherhood. The same year in France, the figure of the witch saw a resurgence in popularity, notably influenced by Mona Chollet’s essay Sorcières: La puissance invaincue des femmes.

Pioneer Moroccan journalist Fedwa Misk launched the participatory feminist webzine Qandisha back in 2011. Accused of turning women against men, she nevertheless offered a platform to men in the interest of inclusivity.

Few cultural projects capture the emancipatory significance of Qandisha’s character. Two eponymous films, released in 2010 and 2020 respectively and directed by men, use the most terrifying aspects of the myth to exaggerate the story and turn it into thrillers. However, cinema has a significant role to play in shaping our collective imagination.

Director Yasmine Benkirane understands this well. In her debut feminist feature film Reines, released in 2022, the figure of Aicha Qandisha, though sometimes approached with a forced mystical angle, becomes the queen of the djins and acts as a benevolent presence to guide the young heroine on her initiatory journey.

In an interview with the Sorociné website, the director explains her desire to “reclaim Qandisha and make her a symbol of feminine revolt, just as European women have reclaimed the figure of the witch.”

And she probably holds one of the keys: the reappropriation of women’s stories by women. To recognize oneself in them, to honor them. What if we were all somehow the heiresses of these lineages of demonized women, as suggested by some contemporary feminist movements?

Somehow, I am myself the archetype of the modern witch: I heal myself with plants, I am sensitive to moon phases, I communicate with animals… and I wonder if it might be up to my generation to break the cycle of these transgenerational violences to re-sacralize the power of the feminine.

If one is not born a feminist but becomes one, through the force of circumstances and the brutality of the world, then I believe it is also up to us to create our own mythology, to know our references, to identify with our heroines, and celebrate our saints. Qandisha, for her part, still struggles to find a narrative that recognizes her as the symbol of resistance she surely was, and what remains of her story will only ever be what we choose to make of it.