Already having challenges to access assistance pre-earthquake – as Syrian children have fewer opportunities to be integrated into Turkish kindergartens – and with schools closed for several weeks in a row, Syrian mothers’ role as caregivers has become increasingly difficult. And it’ll have long-lasting consequences, especially on the psychological level for both the mothers and their young children.

This article is part of a dossier in partnership between SyriaUntold and Orient XXI, exploring the consequences of the devastating earthquake that struck Turkey and Syria in February 2023.

Mariam barely remembers the night she fled war-torn Syria with her family more than 5 years ago. But she still clearly recalls the fear she felt that day.

She was just six years old when, a few hours after midnight, she crossed the border into Turkey with her parents and siblings, trying to hide from armed Turkish border officers. She nervously plays with her fingers, her gaze on her hands rather than her surroundings as she sits inside the tent where she’s been living for the past six months with her parents and younger sister. She then grabs her favorite toy – a baby doll – in an attempt to feel more comfortable and tranquil.

Little did she know a few years later she would experience another traumatic event, this time clearly engraved in her memories. On February 6 at roughly 4am, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake rocked through southern Turkey and northern Syria, resulting in half a million destroyed homes and 50,000 deaths between the two countries, as well as a whopping 5 billions in damage.

Little did she know a few years later she would experience another traumatic event, this time clearly engraved in her memories.

In Turkey, over 1.9 million people have been displaced and, six months since the day of the tragedy, many are still staying in temporary shelters. Humanitarian organizations say children and the elderly have been the most impacted.

According to the United Nations Population Fund, 2.5 million children in Turkey require urgent humanitarian assistance and psychosocial support. Incidents of bullying and self-harm in minors are on the increase, and although no family was left unaffected, the destruction has particularly complicated the already precarious lives of Syrian refugee children.

The 10 south-eastern provinces of Turkey (most of the area affected by the quakes) host almost 2 millions of the 3.7 million Syrians who’ve settled in the country since the beginning of the conflict. Already living in difficult socio-economic conditions before the earthquake, “it comes to no surprise that Syrians have been the most impacted community by this natural disaster,” explains Yara al-Ashtar, 33, a Syrian aid worker with INARA NGO, who works to assess the needs of Syrian families displaced by the earthquakes. “Syrians who don’t have Turkish citizenship aren’t entitled to government aid and so they don’t have the same rights as Turks,” she adds. “They only have the yellow temporary protection card which only allows them to have very limited services, so most of the aid they can receive is from NGOs.”

Incidents of bullying and self-harm in minors are on the increase, and although no family was left unaffected, the destruction has particularly complicated the already precarious lives of Syrian refugee children.

Many have lost their loved ones, and were left to deal with the double trauma of escaping a conflict and finding a new home, only for that safe place to turn into rubble again.

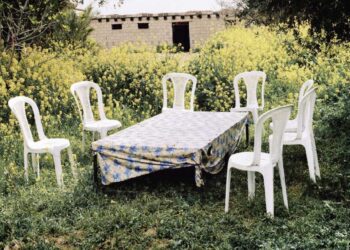

Mariam and what remains of her family now live in a tent in Masal Park, a large green area of Gaziantep, a major Turkish city along the southeastern borders hosting more than half a million Syrians. There are currently about 200 tents in the camp, housing more than 1000 people, mostly refugees from Syria.

The freezing temperatures in winter, then the over 45° in the summer, haven’t made the living conditions tolerable. A few pillows and blankets to cover the tent’s dirty floor and a teapot with plastic cups is all they have to welcome guests.

A few days after they crossed into Turkey, Mariam’s parents – Bayan and Yanal – and their then-three daughters spent some time in a refugee camp managed by the International Organization for Migration near Nizip, a small town in the province of Gaziantep. After many months of paperwork, they decided to give up their initial idea to reach Istanbul and settle in Gaziantep instead, Syrian refugees’ top destination. Back in Syria they had already felt the pain of displacement from their hometown of Homs to a refugee camp in the YPG-held territories in the north-eastern regions of the country.

It took them lots of efforts to integrate and find some balance, but they eventually managed to build their own house in the outskirts of this city, and had their last baby – Mahdia – in Turkey, the parents tell from their tent. Re-living again the trauma of displacement in a tented settlement brought them back ugly memories of their past, adding up to Mariam’s mental wellbeing challenges.

“Our situation was [finally] good. I was working as a laborer. After the earthquake, I was forced to stop and my younger daughter is now suffering from malnutrition,” explains Yanal, 44, Mariam’s father. “The earthquake changed everything. After six months, we’re still in this tent. And we don’t know if and when we’ll ever get out of here.”

Yanal explains that that February night, the roof he built with so much dedication with his own hands collapsed over their heads, killing 3 of Mariam’s siblings. Now Bayan and Yanal are left only with Mariam and Mahdia, who will soon turn 6 years old, the same age Mariam was the night she fled Syria. ”Some bricks fell on my mommy, I was so scared”, Mahdia says tearfully.

Her mother still seems in shock and numb. Bayan, a woman in her thirties, looks tired and way older than her real age. After the earthquake, she began to suffer from severe panic attacks accompanied by severe physical symptoms, which forced her to go to the emergency room.

“Bayan’s job performance declined dramatically, she neglected her young daughters and her husband, and withdrew significantly socially,” explains al-Ashtar, who works to assess Syrian families’ mental wellbeing in the camp and directs them towards the right services. “She was referred to us by the camp administration. Her condition was evaluated by a psychiatrist, followed up with medication, and psychotherapy sessions were allocated to help her overcome the trauma and accept the loss, and she is now on the road to recovery.”

According to Zeynep Bahadir, clinical psychologist with an expertise on natural disasters post-traumatic syndrome, children need more attention than adults in overcoming Turkey earthquake’s traumas.

“Children have seen their whole world crumble before their eyes, and they’re facing a different type of trauma compared to adults, because they’re still growing and developing mentally,” Bahadir explains. “But a limited short-term memory doesn’t necessarily mean they will forget. Sure, they will forget details as their brain is not fully formed, but they might show more serious symptoms that will manifest later in life.”

Bahadir says toddlers’ brain nerve connections during natural disasters can impact their cognitive process and slow it down as they grow up. “If you add the fact that these children are refugees, we witness a cumulative trauma, where the layers of post-disaster distress will add up to those of forced displacement, making full recovery as adults more challenging.”

The expert also adds that Syrian refugees’ cultural understanding is different; language barriers make it harder to access information about aid opportunities in and outside the camps, adding up to the sense of confusion, anxiety and hopelessness that caregivers (their parents or other relatives who are taking care of the children after their parents died) feel, transferring it onto their children.

In the absence of opportunities and income, surviving in tented settlements for Syrians is a daily struggle. Water and food are only available when NGOs show up with limited rations, and a widespread lack of hygiene poses risks of illness and diseases especially among children, while the shock and the little prenatal care can cause spontaneous abortions, unexpected childbirths and create other potential complications. Many new mothers had to give up on breastfeeding because of the psychological shocks and turned to baby formulas, often used in emergency situations but not nutritious enough.

Bahadir says toddlers’ brain nerve connections during natural disasters can impact their cognitive process and slow it down as they grow up.

“I’m no longer working and every day is a struggle to put food on our table,” says Yanal tearfully. “How is Mahdia going to grow strong and healthy without the proper amount of food? I feel so guilty, I thought that after leaving Syria our troubles were over.”

The situation puts an extra stress on caregivers, which then reflects on their children who witness parents struggling, Bahadir explains. “They think: ‘my parents are not strong enough to protect me, so safety doesn’t exist’ which is a mindset they’ll carry on forever as adults. And their parents feel guilty about their parenting skills, because they are not able to provide the bare minimum to their children in such a critical situation.”

She adds that providing children with psychosocial support, play and learning, are immeasurably important in ensuring some temporary stability, as well as long-term wellbeing.

Six months into the tragedy, children like Mariam and Mahdia seem numb to everything happening around them. They don’t go to school, and although they used to have more playtime moments when few volunteers showed up to entertain them for a couple of hours in the weeks immediately following the quakes, they now seem abandoned to their own destiny, as their parents are caught up in their daily struggles, and humanitarian organizations barely pay them visits.

Children below the age of six make up one third of those currently living in tents, according to charity groups. Bahadir explains that children’s traumas differ according to their age range. “Preschool children like Mahdia especially can experience separation anxiety, wanting to remain closer to their parents than before, and often feel the need to cry,” she says. “While children at school age like Mariam can be angry or aggressive, and may even try to hurt their siblings physically.” For a caregiver with children in both these age range groups, parenting can become extra challenging.

Six months into the tragedy, children like Mariam and Mahdia seem numb to everything happening around them. They don’t go to school, and although they used to have more playtime moments when few volunteers showed up to entertain them for a couple of hours in the weeks immediately following the quakes, they now seem abandoned to their own destiny.

Bayan feels that her daughters have become distant from each other since the earthquake. “Even as sisters, they don’t play or talk much to each other when they’re alone,” she says with clear worry in her voice. Having already lived through untold losses, mental health support is crucial for Syrian children displaced in Turkish camps. Isolation from Turkish peers, moreover, is only highlighting divides and increasing racist attitudes towards Syrian children and their parents.

Al-Ashtar explains that lately authorities have deliberately segregated Syrian refugees from members of the displaced local population while planning new camps, in order to avoid tensions and escalations of violence.

Being exposed to such threats, particularly after a racist, violent presidential campaign for the Turkish presidential elections last May scapegoated Syrian refugees, with the current president vowing to send back 1 million refugees, Syrian children no longer feel welcome. Some of them, like Mahdia, have never seen a homeland other than Turkey, and her grasp of Syria only comes through the stories of her parents.

But they barely talk to her these days, let alone telling her stories about Syria and her origins. “We are afraid to say we’re Syrians; after the earthquake, things got worse for us. We feel nowhere is any longer safe for us, and not just because of the ground shaking, but because people blame us for everything,” Yanal says.

Although the natural disaster from six months ago has put millions of traumatized Syrian refugees in Turkey through a sense of loss and displacement, yet again, Bahadir highlights it is important for caregivers to not ignore their children, and instead try to explain them in simple words what happened, without fussy or confusing explanations.

And as the coming months look darker than ever for Syrians in Turkey, they have learnt to find solace and hope in each other.

“Syrian families as a whole live in harsh, tragic conditions. It is not easy for any family to provide support to another family,” explains al-Ashtar. “But it caught my attention that families whose origins belong to the same area in Syria mostly gathered in the same camp or the same area, and there is a state of support and social solidarity.”

Families like that of Mariam have resorted to helping each other as they can. When Bayan is missing some ingredients for the few foods she manages to cook, or needs someone to look after her children while her husband is away looking for work opportunities to make ends meet, she relies on her tent neighbors, another small family with a 4-year old child expecting to deliver their second before the end of the year. Despite the limited resources, Bayan’s neighbors say they’re happy to look after Mariam and Mahdia, or to share together the little food they manage to put together.

“We collect and put together in a common pot the little money we manage to save, to buy collective groceries, like bulgur or spices,” Bayan says. “Or we rely on some donations from fellow Syrians who haven’t lost their jobs or homes. What else can we do? We do our best to at least keep alive the children Allah hasn’t taken away from us. But I wish I could do more, at least buy a small toy to let my daughters…,” Bayan interrupts the sentence, suffocating her tears.

Mariam runs towards her, patting her shoulders to try and cheer her up, or at least, not make her feel guilty. “I know she’s doing her best, but she needs me to remind her,” the kid says.

This story was supported by the Early Childhood Global Reporting fellowship from the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia Journalism School.