Janbert Gazali, 25, still remembers the moments of panic he went through when he woke up to the news that his city of Iskenderun, in the southern Turkish province of Hatay, completely collapsed to the tremors of a 7.8-magnitude earthquake.

Just a little over a year ago, on that early February morning, he was studying in Italy – on the other side of the Mediterranean. That day living so far away from his homeland and loved ones felt more painful than ever.

“Even though our family survived the earthquake with fewer damages than elsewhere, the earthquake hurt us, just like everyone else living in Hatay,” Gazali, who one year later is now back to Iskenderun, says. “That night was a very difficult night for all of us as a community and had unforgettable effects.”

At 4.17am, then again shortly after 12pm, a two-folded earthquake followed by thousands of aftershocks rocked through south-eastern Turkey and north-eastern Syria, killing more than 50,000 and causing a five billion-worth damage on private buildings and cultural sites.

In Hatay – a province that had survived many disasters in its 24,000 years of history – the impact of the destruction had a more resounding echo than anywhere else in the earthquake region, with almost 25,000 overall deaths and dozens of cultural hubs and places of worship completely obliterated.

“Not only our buildings, but also our society was greatly injured in the earthquake, and the churches of our community suffered great damage,” says Fethullah, the patriarch of the Gazali family who’s of Christian religion and Arabic heritage.

Although unusual for a country that proudly defines itself as heterogeneous and monolingual, Hatay’s peculiarity is its dual Turkish and Arab identity. The Arabic language entered the southern Mediterranean region of Hatay already in the seventh century, as a result of the Arab conquests. The Ottomans ruled the area between the 16th and the 20th centuries, then when the Empire fell and Syria gained its independence in 1920, Hatay became part of this newly-established Arab republic. While under French colonial influence, Syria however lost Hatay to a deal between France and Turkey that entered the area in 1938. A year later, after a controversial referendum, Hatay officially joined the new Turkish republic ruled by Ataturk. Overnight, the new border turned families and neighbors into foreigners, changing the language too.

“Until annexation, Turkish and Arabic co-existed for centuries. But under Turkey’s republican policies the use of Arabic began to decline,” explains 69-year-old Josef Naseh, a historian from Antakya, Hatay’s main city, who’s an expert on the language and culture of the area. “Even though the February 6 earthquake did not kill by discriminating on language and ethnicity, and therefore we cannot officially say or prove that those with Arab heritage have died more, this disaster certainly gave a huge blow to our whole population and traditions,” he adds.

In 1971, 36% of the population in Hatay was Arabic-speaking. In 1996, there were an estimated 500,000 speakers of a North Levantine Arabic dialect in Turkey. The dialect spoken in Hatay, however, is an old version of Levantine dialect that did not evolve along with the Syrian one as the two countries were separated by borders after the 1938 annexation. The Arabic today spoken in Hatay got stuck in time, with older terms still commonly used and never acquiring new slangs of Syria that naturally developed in the past century.

After the earthquake, with thousands of speakers of this dialect who’ve lost their lives – particularly the elderly who preserved the tradition – a crucial part of the oral heritage of this Arabic-speaking community was lost forever.

With many survivors left with nothing other than attempting to migrate to Europe, it’ll be an even more complicated, but meaningful, challenge to preserve it after the tragedy, considering especially its symbolic meaning of reminding about Turkey’s and Syria’s shared past in times of hatred towards Syrian refugees in post-elections Turkey. “The real devastation this earthquake created is spiritual, because now more than ever we need people who can carry on the mythology, the faith, the culture of this land amid attempts to erase it,” Naseh says.

In the late 1930s, the first direct threats to Arabic came when compulsory education became only available in Turkish and a ban on speaking Arabic in public was imposed until the end of the last century. Arabic as a language of education and culture slowly started to decline, especially among younger generations.

“In my daily life, I speak Turkish with my family and brother, but since my grandparents do not know Turkish, I speak only Arabic with them,” Janbert says while he passes on a book with Arabic scripts to Raymond, his younger sibling. From their home in Iskenderun, overlooking the pristine waters of the Mediterranean Sea, the Gazali family is unsure of their homeland’s future. “Hatay is the area that lost most properties and lives in the earthquake. We have many cultural places and architectural beauty that have been damaged so their overall number decreased,” Janbert says. “But their symbolic value has never disappeared. Since our tradition and culture are based on solid foundations that have existed for a long time, it would not be easy for them to disappear.”

The Gazali family has deep roots in the area, like most people in their community. “Today, you can still see Beit Ghazaleh, our family mansion, in Aleppo!,” Fetullah says with pride, pulling out an old black and white photo from the living room’s drawer. “After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Atatürk would stay in our great-grandfather’s mansion when visiting Aleppo.”

The Gazali’s origins date back to the lineage of King Raymond from the time of the Principality of Antakya. It was a noble family that came to the Middle East from France and Italy at that time, settling in the city of Homs in Syria and then in Aleppo, where they were active in trade. Rizkallah Gazali, Janbert’s great-grandfather, pioneered the development of trade from Europe to the Middle East and the Levant. He took over the Damascus Province of the Ottoman Empire and Syria. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, some Gazali family members remained in Aleppo, others returned to Europe (Switzerland, France and Italy), but the majority moved permanently to Iskenderun, now part of Hatay, which was Syrian territory at that time. “We’ve been part of the Middle East for centuries, preserving our Arab and Christian culture, faith and traditions. We will keep doing that with pride,” Fetullah says.

Although there are no updated official statistics on language use or on ethnic groups in Turkey since the late 1990s, it is clear that in the province of Hatay most people descend from Arabs, and feel Arab, as they’ve been maintaining this dual identity with the majority of people trying to keep their bilingual status. “For us, it would not be right to say that my ancestors came from Syria. Hatay, the land we are in, was already a Syrian city. We did not come here, we were already here and we are still here. So we didn’t come to Syria, the Turks came here,” Raymond says.

Alawites, Christians and Jews of Arab heritage distance themselves from Turks, with whom there are virtually no marriage relationships. But international marriages between ethnic Arabs of Hatay with Turkish citizenship and Syrian nationals have become the norm since the annexation, with the goal of retaining the Arabic language.

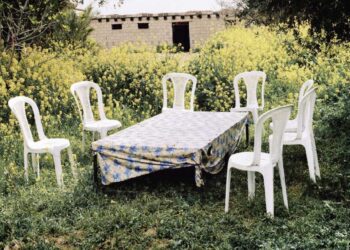

In Kırıkhan, a seaside town in Hatay heavily impacted by the earthquakes, the Ağgün family of four was forced to move to a container 20 days after the tragedy.

The earthquake destroyed their home, but not their spirit. Lara, 9, is the family’s eldest daughter. Syrian from her mother’s side and Turkish from her father’s side, she is bilingual at birth. “I miss going to school and learning new things, especially math,” she says as she holds her precious coloring book that reminds her of her school days. With no functioning elementary schools nearby, she’s had to rely on sporadic informal classes in the container city she’s been living in with her family, and focus on helping her parents look after her elder sister, who suffers from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) in need of constant care.

“At home we all speak Arabic, so Lara has had fewer opportunities to advance in Turkish,” her mother Hala – originally from the seaside Syrian city of Latakia – says with a tired smile. During the early days of the war, she crossed the border into Turkey, where she had an arranged marriage with Mehmet Ağgün, now her husband. Despite not being able to return to her native Latakia ever since – despite before the eruption of the conflict, people from her city would come and go daily – she says she doesn’t miss home that much, even though she could never imagine to become homeless not because of a war in her country, but a natural disaster in her land of adoption. “Here I’ve felt welcomed, and the culture and language are so similar that sometimes I feel like I’ve never left Syria,” Ağgün adds.

Many of the 3.6 million Syrian refugees who’ve fled war-torn Syria and settled in Turkey have chosen the south-eastern province of Hatay. That was dictated by the cultural and language affinity, as well as geographical proximity with mainland Syria, but also because it’s in Hatay that they’ve felt most welcome.

In Samandag, a major coastal town, a murali by the beachside walk still standing after the earthquake proclaims in Turkish that “Syrians are our brothers”. In a town that colloquially goes by its Arabic name – Suedeyeha – rather than its official Turkish title, this sentiment may seem to go against the current of widespread diffidence against Syrian refugees carried out during last year’s presidential elections, threatening large-scale deportations.

“We used to trade food and tobacco everyday with Syrians,” says Fetullah Gazali. “The Syrians would come back and forth for daily out-of-country trips to enjoy some vacation time.” According to locals, about 500,000 Syrian refugees have ended up in Hatay’s towns and villages since 2011, pushing the number of Arabs in the province up from 34 to 47 per cent, according to a 2018 report from the Washington Institute.

Despite the divisions caused by the war in mainland Syria, Hatay’s Arab population – consisting mainly of Alawites, Christians and Jews – the majority of refugees, who are of Sunni background, have been warmly welcomed.

The normality of cross-border marriages is also what saved many Syrians from living in a war zone. 30-year-old Ahmad Nached’s grandmother was originally from Hatay; when the region was annexed to Turkey, she received Turkish citizenship. But being an ethnic Syrian, her family arranged her marriage with a man from Aleppo at the end of WWII. Little did she know that her Turkish passport passed on through generations would save her grandson more than 50 years later.

“That same passport was my safety,” Nached says. In 2012, shortly after the first protests in which he took part as a teenager, his whole family moved to Gaziantep thanks to that Turkish citizenship inherited from their grandmother from Hatay. Nached says he still feels more Syrian than Turkish, but he’s grateful for this ancestral connection that saved him. “If it wasn’t for this special connection between Hatay and northern Syrian, I would’ve probably been stuck in Syria, or resorted to come to Turkey through many challenges and dangerous routes.”

Syrian refugees’ arrival coincided with a slow but steady decline in Arabic language usage in the region in recent decades, according to Naseh. “About 45% of Hatay residents have Arab origins, but the number of those who speak Arabic as a written language is decreasing, with Turkish becoming more the norm,” he says. “The new generation cannot speak fluently or understand some Arabic words, and a part of our youngest youth does not know it at all.”

However, there has been a counter-movement for a few years now with the mass arrival of Syrians, with the two versions of Syrian dialect intertwining in the streets, alongside Turkish.

While Janbert packs up his clothes to move out of town for a job he got in the northern region of the country, he feels sad of having to leave his homeland again, especially after all it suffered over the past year. “Hatay was an Arab land before joining Turkey and some people living here still define themselves as Arabs. When you go to some places in Hatay, only Arabic is spoken, only Arabic food is eaten and even Arabic songs are played at weddings,” he says. “We can literally say that this geography is a part of the Arab world, despite being in Turkey. Although these lands are fewer than before, they have hosted and continue to host a strong population of Arabs, Christians, Sunni, Alewis and Jews trying to live in peace and preserve our centuries-old tradition. He pauses pensively, then smiles:

“I carry this conviction with me wherever I go.”